Science news this week: Spiders on Mars and an ancient Egyptian sword

Sept. 21, 2024: Our weekly roundup of the latest science in the news, as well as a few fascinating articles to keep you entertained over the weekend.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Rarely do we get the opportunity to hum a classic David Bowie song while thumbing through the latest science news, but this week we saw the return of spiders on Mars. No, they're not real arachnids scurrying across the Red Planet's surface — instead they're part of a geological feature known as araneiform terrain. These dark, crack-like structures form when carbon dioxide seasonally erupts from the planet's surface and resemble spiders scurrying across the terrain when viewed from a great height. And now, for the first time they have been recreated on Earth.

But these "spiders" are not the only thing we've had to keep an eye on from space: There is the new 'mini-moon' taking a short spin around our planet; the discovery that Earth may have once worn a Saturn-like ring; and the prospect of space trash leading us to intelligent aliens.

'Ramesses II' sword

3,200-year-old ancient Egyptian barracks contains sword inscribed with 'Ramesses II'

Archaeologists in Egypt recently unearthed the 3,200-year-old remains of a military barracks containing a sword with hieroglyphs depicting the name of Ramesses II.

Remains of pottery containing fish bones were also found on the site, alongside multiple cow burials.

The bronze sword was found in a small room in the barracks, near a less-protected area where an enemy could infiltrate. This is an indication that this sword was intended for fighting and not just for show, Ahmed El Kharadly, an archaeologist with the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities who led excavations at the site, told Live Science in an email.

Discover more archaeology news

—Rare skeletons up to 30,000 years old reveal when ancient humans went through puberty

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Life's Little Mysteries

Why do we forget things we were just thinking about?

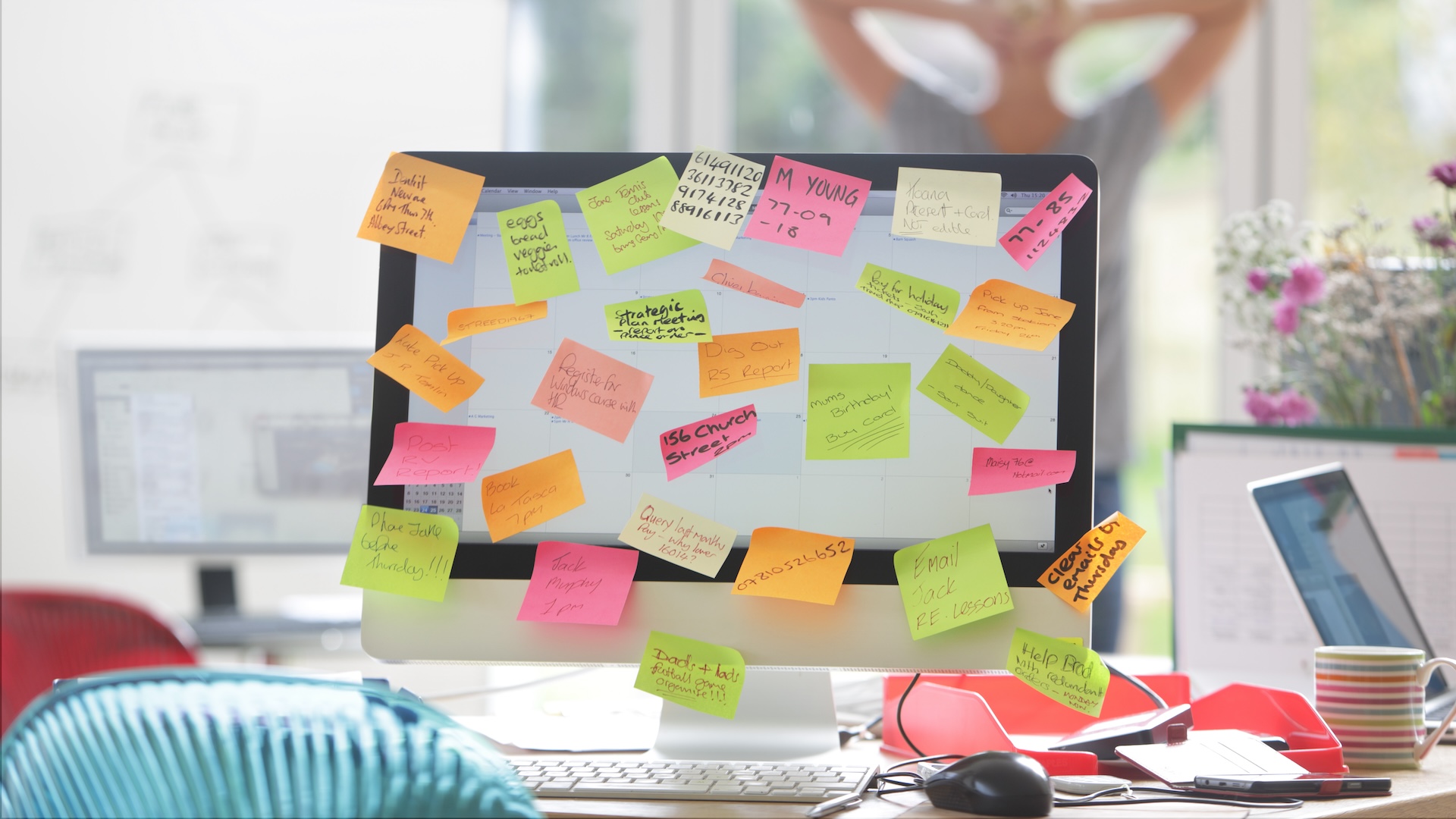

Have you ever walked into a room and forgotten why you went in there, or been about to speak but suddenly realized you had no idea what you were going to say? The human brain normally balances countless inputs, thoughts and actions, but sometimes, it seems to short-circuit. So what really happens when we forget what we were just thinking about?

Sea monster jaws discovered

80 million-year-old sea monster jaws filled with giant globular teeth for crushing prey discovered in Texas

A giant mosasaur's fossilized jaw fragments still hold the animal's blunt, mushroom-shaped teeth.

The two fossil fragments, discovered in Texas, give us an insight into the lifestyle of Globidens alabamaensis, which may have reached lengths of up to 20 feet (6 meters). The teeth show the brute force mosasaurs brought to bear on their prey.

"These structures … are great for impact attacks — for shell crushing. If something is getting away and you shatter it, that's kind of it," Bethany Burke Franklin, a marine paleontologist and educator at Texas Through Time fossil museum in Hillsboro who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

Discover more animal news

Also in science news this week

- Pregnancy shrinks parts of the brain, leaving 'permanent etchings' postpartum

- Biggest black hole jets ever seen are as long as 140 Milky Ways

- Record-breaking fires engulf South America, bringing black rain, green rivers and toxic air to the continent

Science Spotlight

3 bold ways cities are already adapting to climate change

Milan's marble facades and narrow, stone-paved streets look elegant and timeless. But all of that stone emits heat and does nothing to absorb rain, and temperatures and flooding in the posh Italian city are only predicted to increase in the coming decades.

In Jakarta, black floodwaters already rush into homes every winter along the Indonesian city's many rivers. That water is filled with sewage and harbors disease, but many people can't afford to move. Soon, climate change will put more of Jakarta — and many other low-lying cities — below sea level.

And in arid San Diego, water is already treated like a precious commodity. As drought increases in the coming years, protecting this resource will become even more important.

Human-caused climate change is transforming weather patterns and shifting ecosystems around the globe. Cities will have to respond, and some are already taking bold steps.

Each of these three cities offers a different roadmap for climate adaptation that has lessons for other places around the world. And while no single approach will be a silver bullet, each offers a hopeful vision of how we can learn to live and thrive on a warming planet.

Something for the weekend

If you're looking for something a little longer to read over the weekend, here are some of the best long reads, book excerpts and interviews published this week.

- 'I have never written of a stranger organ': The rise of the placenta and how it helped make us human [Book excerpt]

- What is the dead internet theory? [Explainer]

- 'What is normal today may not be normal in a year's time': Dr. Dinesh Bhugra on the idea of 'normal' in psychiatry [Interview]

Science in pictures

Weird waves that 'shape life itself'

Mesmerizing microscopic footage showing "waves" inside a developing fly embryo has won the 14th annual Nikon Small World in Motion competition.

Bruno Vellutini's video was chosen from among 370 entries as overall winner of the competition on Tuesday (Sept. 17).

He captured the film using light sheet microscopy, a technique in which a focused "sheet" of laser light illuminates a sample to produce high-resolution 3D images of living cells, tissues and organisms.

Follow Live Science on social media

Want more science news? Follow our Live Science WhatsApp Channel for the latest discoveries as they happen. It's the best way to get our expert reporting on the go, but if you don't use WhatsApp we're also on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Flipboard, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky and LinkedIn.

Alexander McNamara is the Editor-in-Chief at Live Science, and has more than 15 years’ experience in publishing at digital titles. In 2024 he was shortlisted for Editor of the Year at the Association of British Science Writers awards for his work at Live Science. He has previously worked at New Scientist and BBC Science Focus.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus