'Spiders on Mars' fully awakened on Earth for 1st time — and scientists are shrieking with joy

Researchers have recreated the bizarre spider-like features seen on the surface of Mars for the first time ever. The breakthrough could help unravel further mysteries surrounding the static Martian arachnids.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

NASA scientists on Earth have recreated the creepy black "spiders" that litter the surface of Mars. The breakthrough left the researchers "shrieking" with joy and could help uncover further secrets about the mysterious structures.

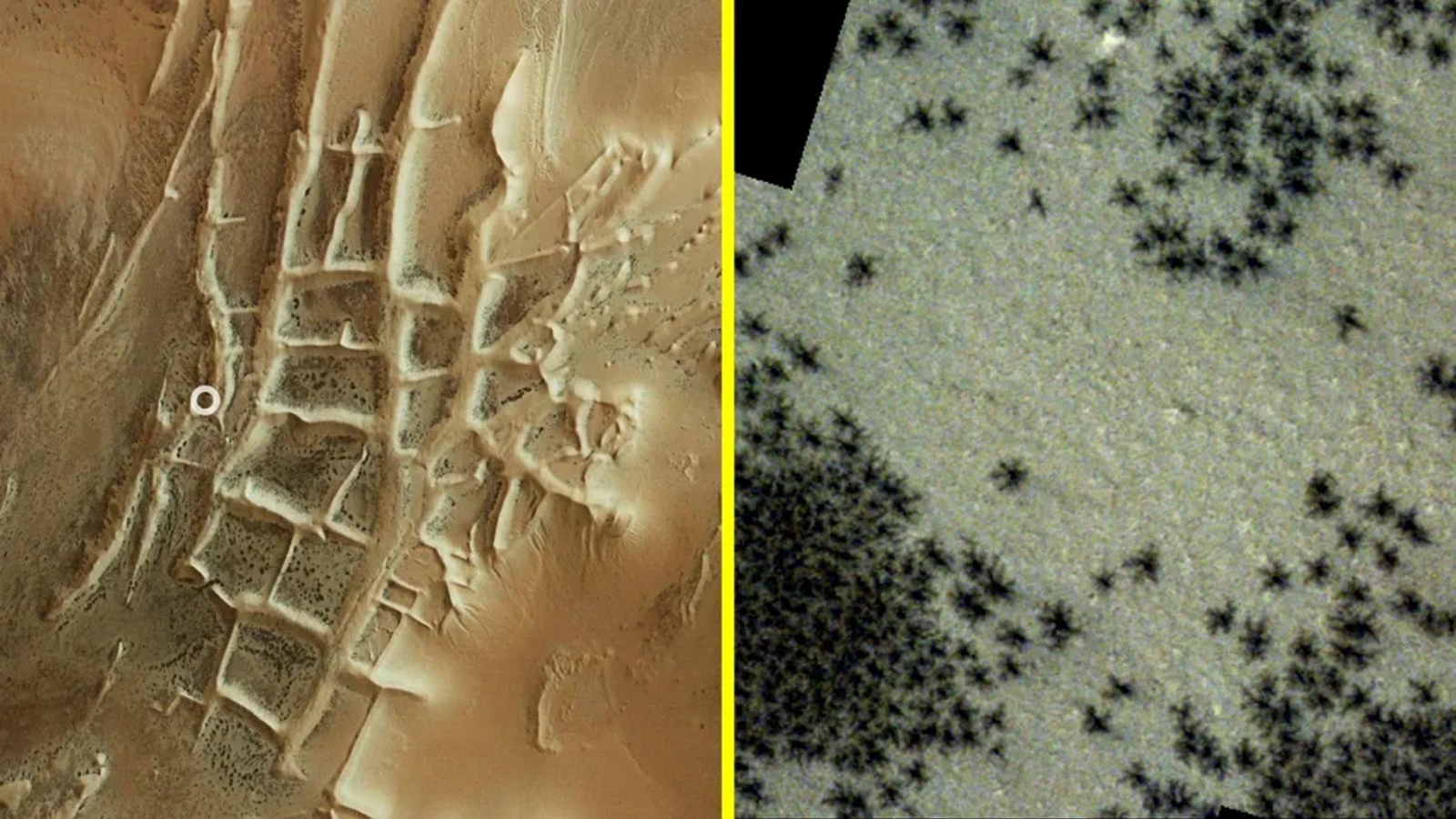

"Spiders on Mars" is the name given to a geological feature, known as araneiform terrain, that is visible in multiple locations on the Red Planet. In these places, hundreds of dark crack-like structures appear on the planet's surface, each with potentially hundreds of individual lines, or "legs." When viewed from above, these tightly grouped deformations, which can be more than 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) wide, look like a hoard of spiders scurrying across the Martian landscape.

Mars orbiters first spotted the spiders in 2003, and the features have continually popped up in satellite images ever since. At first, these stationary arachnids were a complete mystery, but scientists eventually determined that the spiders form when carbon dioxide (CO2) ice on the planet's surface suddenly sublimates — or turns into gas without first melting into liquid.

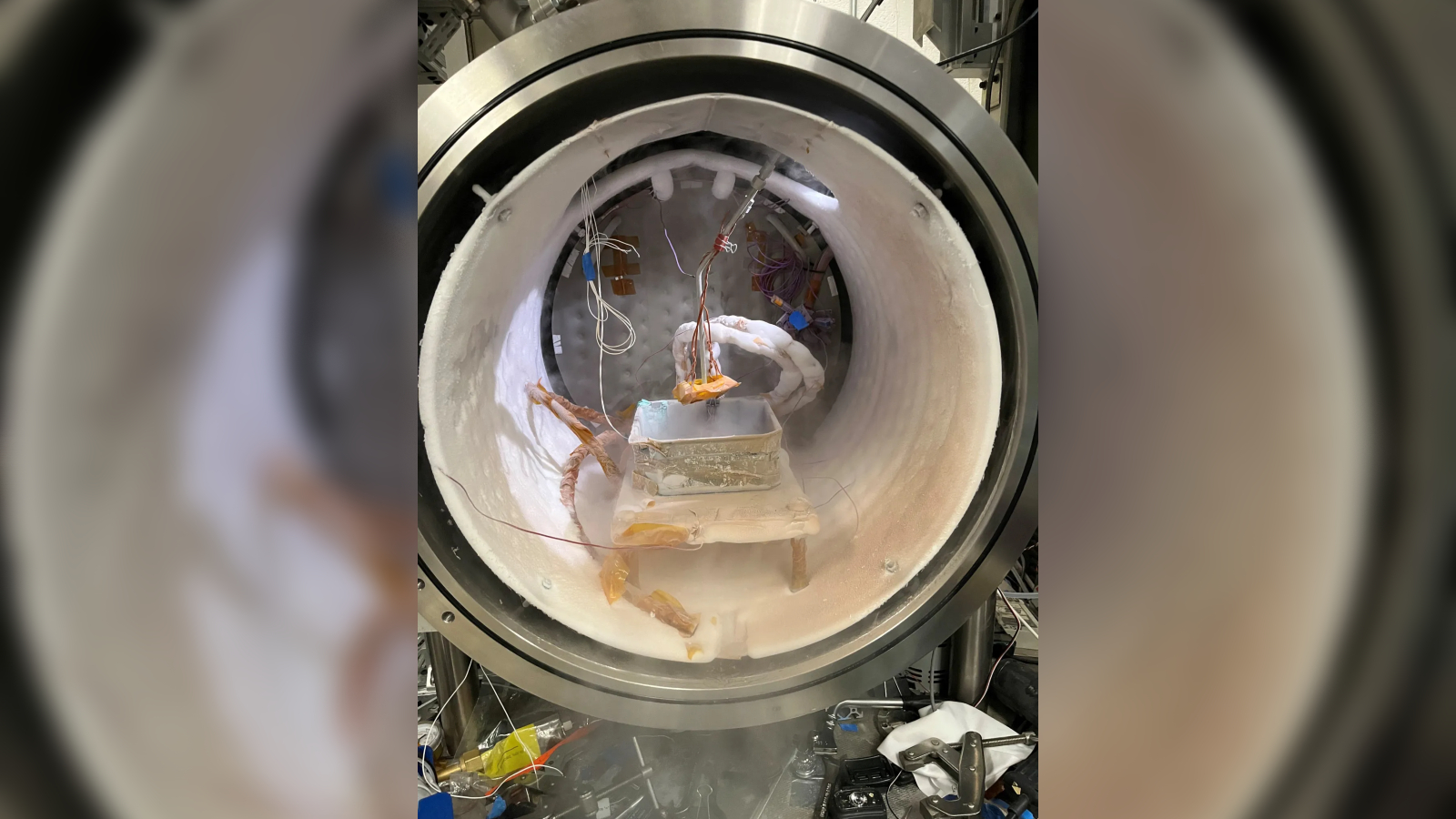

In a new study, published Sept. 11 in The Planetary Science Journal, researchers mimicked this process on a smaller scale using a specialized laboratory chamber to create a near-perfect miniature version of the spiders.

For the study's lead author Lauren Mc Keown — a planetary geomorphologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California, who has been working on recreating these spiders for five years — the moment of finally birthing the Martian critters was almost too much to handle.

"It was late on a Friday evening [when the experiment succeeded] and the lab manager burst in after hearing me shrieking," Mc Keown said in a statement. "She thought there had been an accident."

Related: 15 Martian objects that aren't what they seem

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2021, Mc Keown led a study that first explained how the spiders form — via a pathway known as the Kieffer model.

This model showed that, during Martian spring, sunlight shines through slabs of CO2 ice on the surface, heating the ground below. This, in turn, causes some of the ice to sublimate into gas, creating a pressure buildup within the ice slabs. When the pressure gets too high, the ice cracks, which enables the gas to escape. As the gas seeps out of the ice, it takes a stream of dark dust and sand from the surface, leaving behind spider-like scars that appear when the ice fully melts during Mars' summer.

In the new study, the researchers put the Kieffer model to the test by recreating these steps in a wine barrel-size chamber at JPL, known as the Dirty Under-vacuum Simulation Testbed for Icy Environments (DUSTIE), which recreated Mars' extremely low pressure and temperature — minus 301 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 185 degrees Celsius).

The team placed a simulated Martian soil into the chamber and covered it with CO2 ice. They then heated the mixture with a lamp placed beneath the simulated soil to replicate the warming effect of the sun.

"It took many tries before Mc Keown found just the right conditions for the ice to become thick and translucent enough for the experiments to work," NASA representatives wrote in the statement. But finally, the ice cracked open and gas seeped out of the hole for around 10 minutes before the frozen CO2 eventually disappeared and left behind one of the iconic spiders.

The new study also reveals a hidden step in the Kieffer model: Ice also formed within the ground, which caused it to crack open along with the ice. This could explain why the spiders' legs have such a zig-zag shape, the researchers wrote.

"It's one of those details that show that nature is a little messier than the textbook image," study co-author Serina Diniega, a planetary scientist at JPL, said in the statement.

The researchers plan to perform similar experiments in order to solve the biggest remaining mysteries about the Martian spiders, including why they form in some places on Mars but not others and why they don't seem to be growing in number every year.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus