Hundreds of black 'spiders' spotted in mysterious 'Inca City' on Mars in new satellite photos

Every spring, creepy black 'spiders' sprout up on Mars as buried carbon dioxide ice releases dusty geysers of gas. New ESA images show the phenomenon has begun in the strange Inca City formation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Arachnophobes need not fear: A new European Space Agency (ESA) image of Martian "spiders" actually shows seasonal eruptions of carbon dioxide gas on the Red Planet.

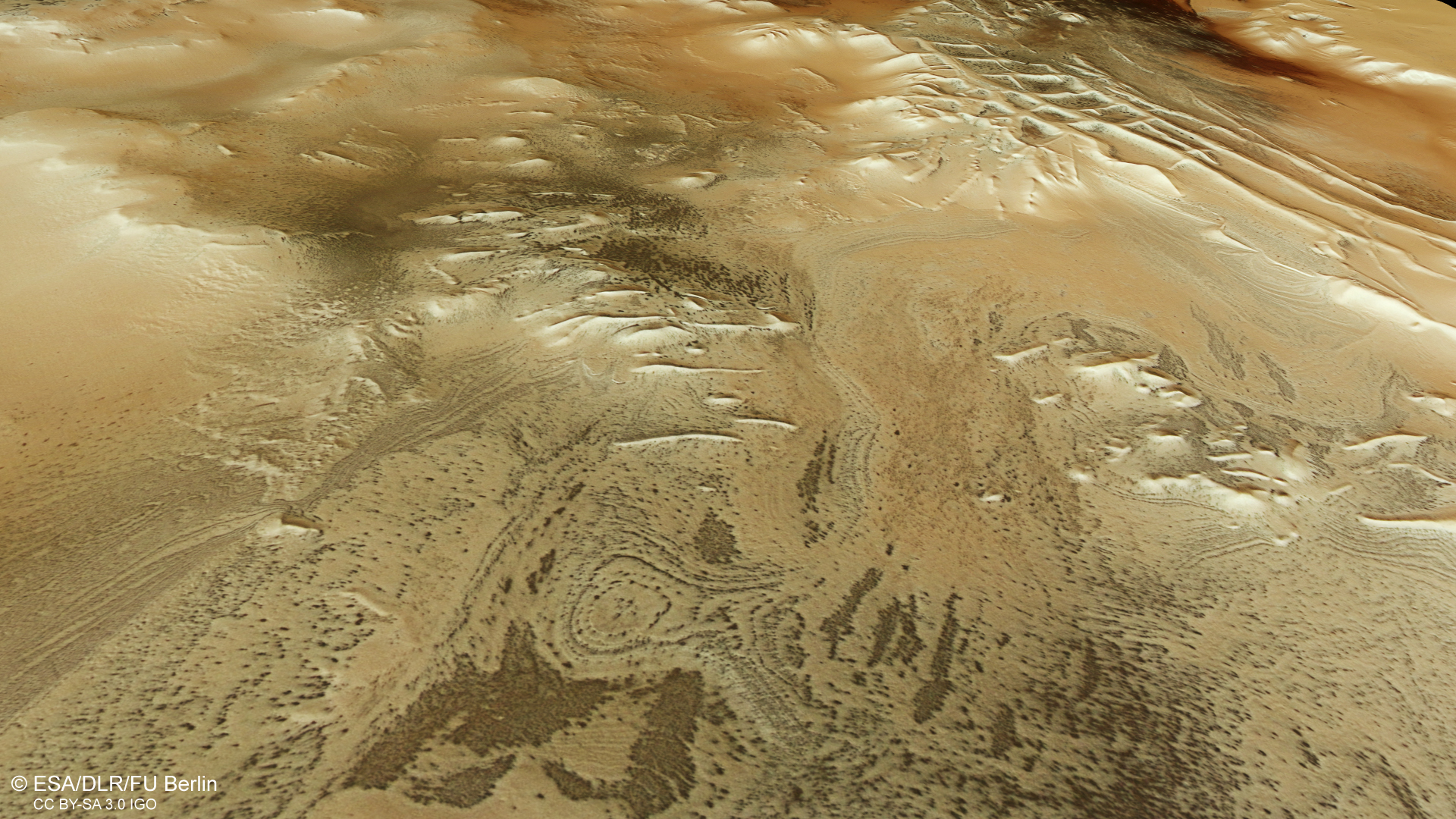

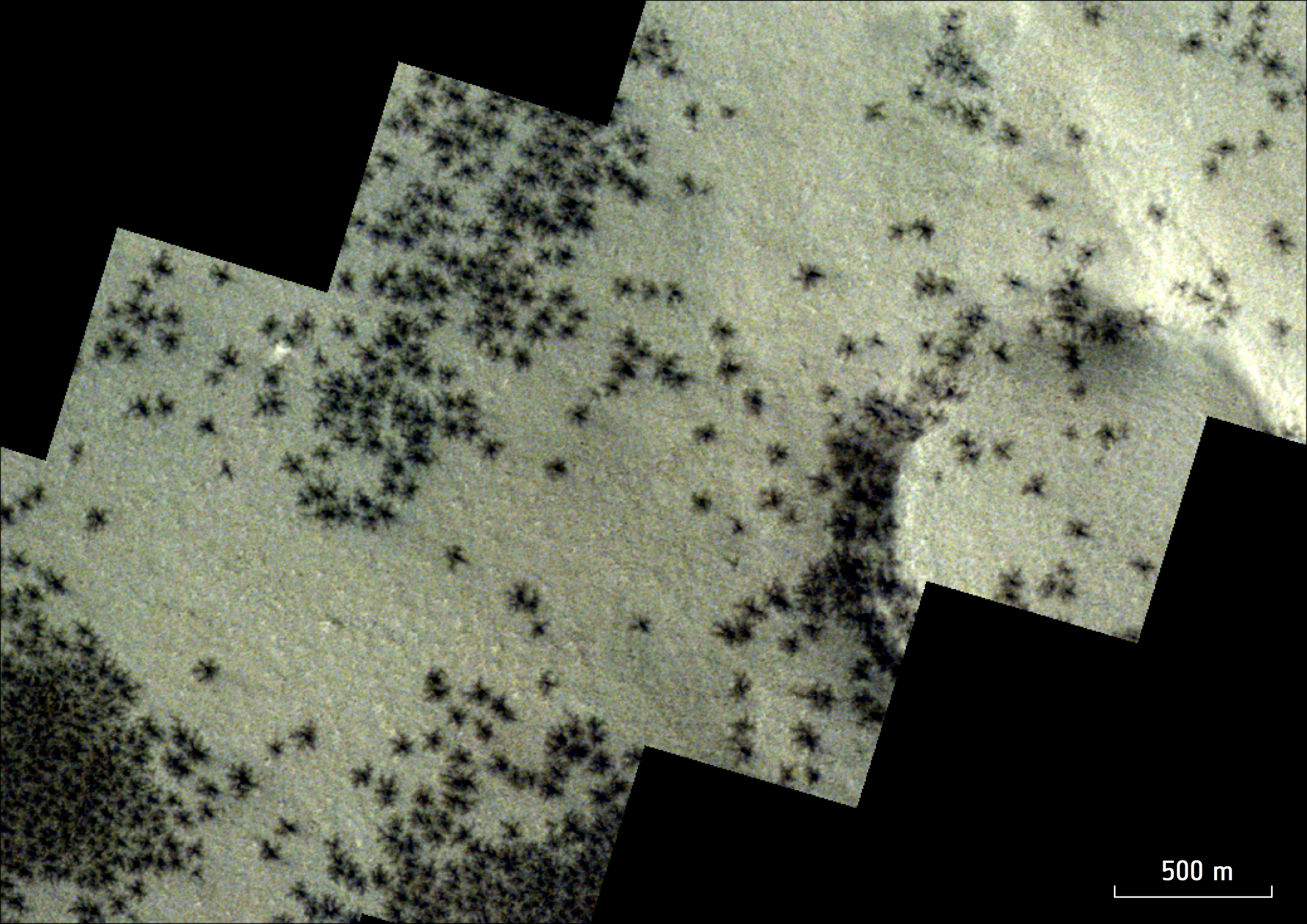

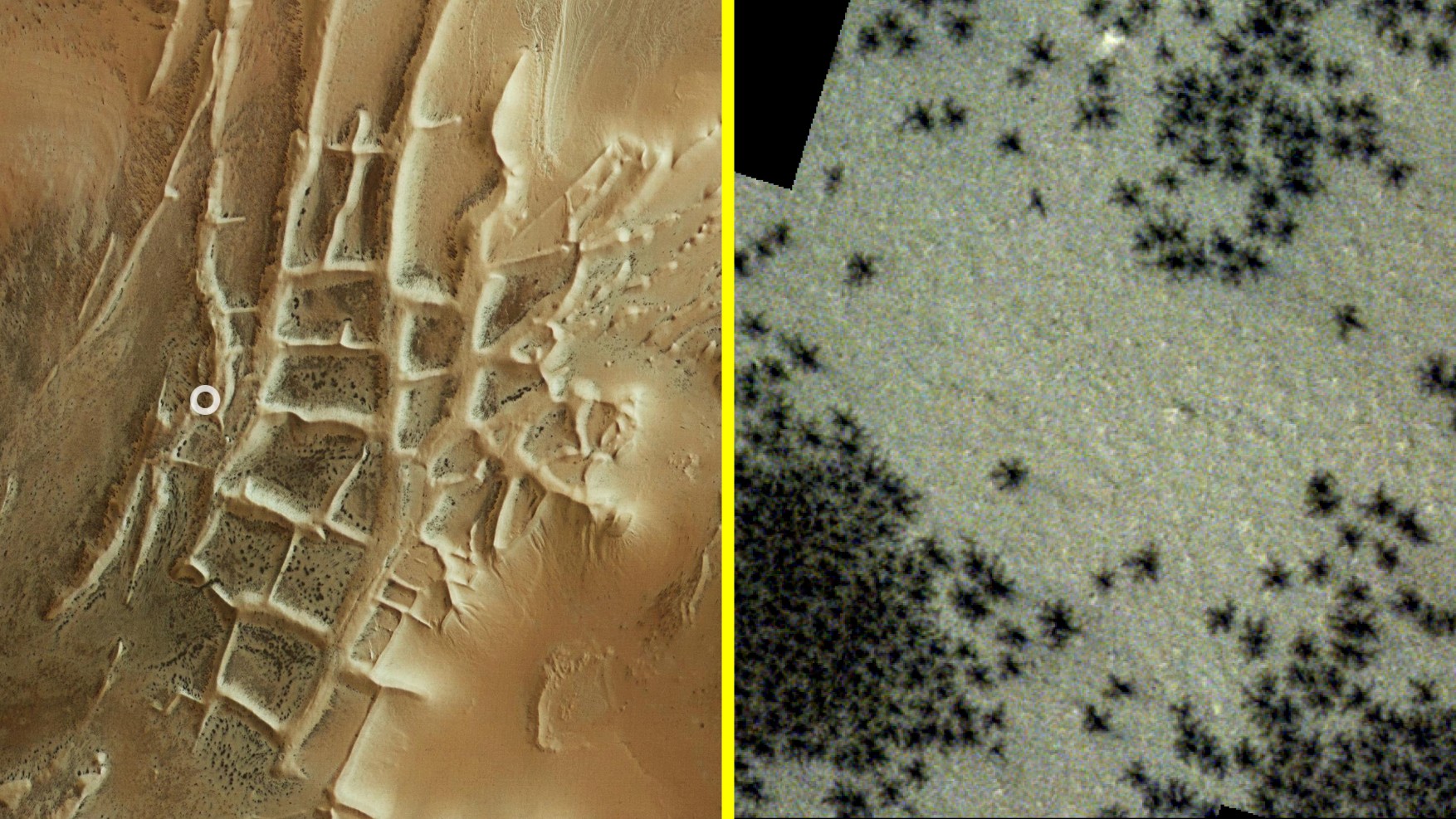

The dark, spindly formations were spotted in a formation known as Inca City in Mars' southern polar region. Images taken by ESA's Mars Express orbiter and ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter show dark clusters of dots that appear to have teeny little legs, not unlike baby spiderlings huddling together.

The formations are actually channels of gas measuring 0.03 to 0.6 miles (45 meters to 1 kilometer) across. They originate when the weather starts to warm in the southern hemisphere during Martian spring, melting layers of carbon dioxide ice. The warmth causes the lowest layers of ice to turn to gas, or sublimate.

Article continues belowAs the gas expands and rises, it explodes out of the overlying ice layers, carrying with it dark dust from the solid surface. This dust geysers out of the ice before showering down onto the top layer, creating the cracked, spidery pattern seen here. In some places, the geysers burst through ice up to 3.3 feet (1 m) thick, according to ESA.

Related: Single enormous object left 2 billion craters on Mars, scientists discover

Inca City is also known as Angustus Labyrinthus. It's named for its linear, ruin-like ridgelines, which were once thought to be petrified sand dunes or perhaps remnants of ancient Martian glaciers, which could have left high walls of sediment behind as they retreated.

In 2002, however, the Mars Orbiter revealed that Inca City is part of a circular feature approximately 53 miles (86 km) wide. This feature may be an old impact crater — suggesting that the geometric ridges may be magma intrusions that rose through the cracked, heated crust of Mars after it was hit by a renegade space rock. The crater would have then filled with sediment, which has since eroded, partially revealing the magma formations reminiscent of ancient ruins.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Search for Life on Mars: The Greatest Scientific Detective Story of All Time — $18.99 on Amazon

Although these may not be real spiders on the Red Planet, we still hold out hope that one day we will find signs of life on Mars — and leading the way in our search is the Perseverance rover mission. This, along with all the missions that came before it, are expertly explored in the book "The Search for Life on Mars" by Nicholas Booth and Elizabeth Howell. We love all the work she does at our sister site Space.com, so we know you'll love this book too.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus