Science history: Alexander Fleming wakes up to funny mold in his petri dish, and accidentally discovers the first antibiotic — Sept. 28, 1928

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Milestone: Discovery of penicillin

Date: Sept. 28, 1928

Where: St Mary's Hospital, London

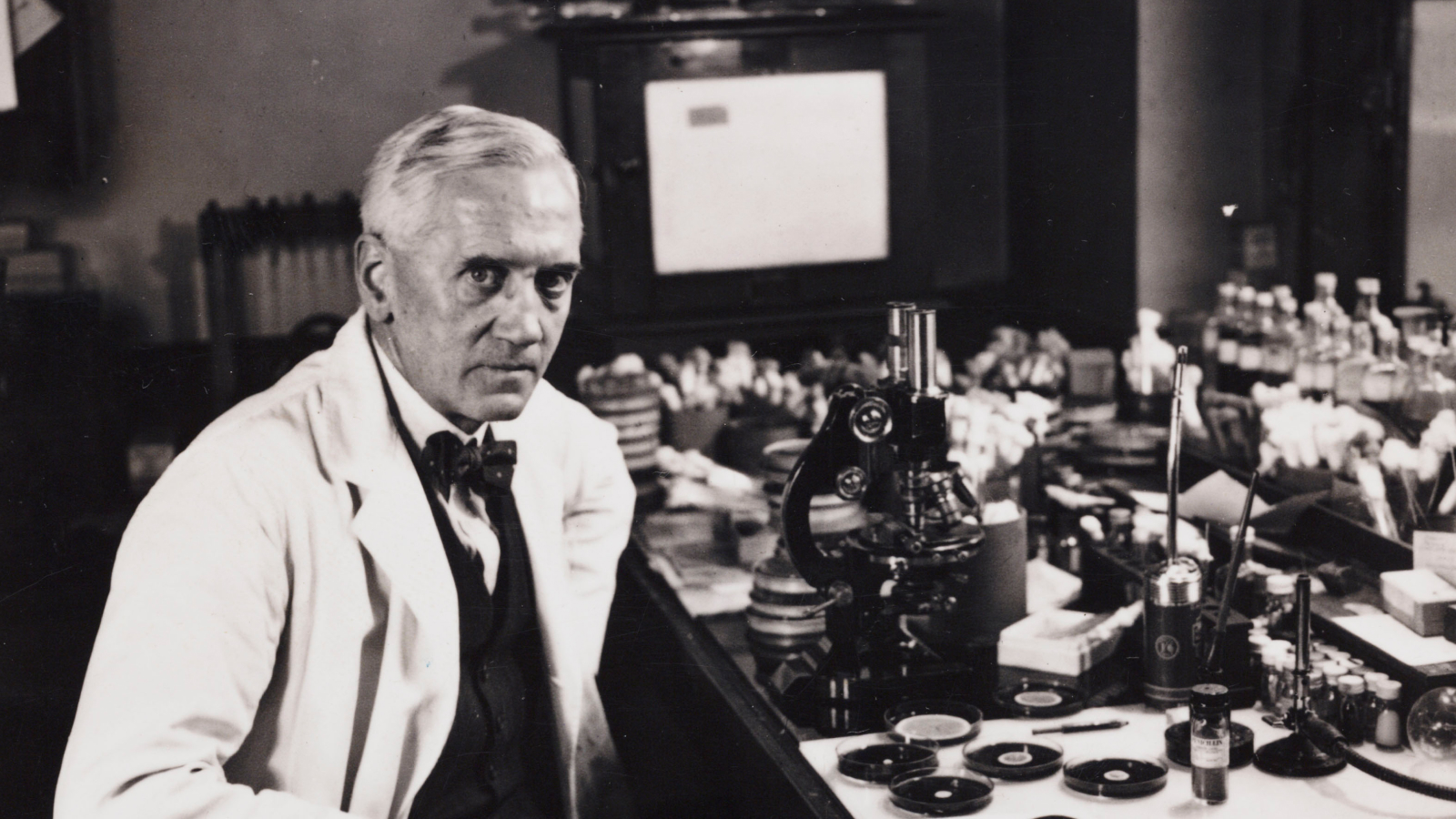

Who: Scottish microbiologist Alexander Fleming

On Sept. 28, 1928, Alexander Fleming woke up to check on his experiments investigating bacterial growth — and accidentally discovered the world's first antibiotic.

The Scottish physicist and microbiologist had been doing experiments in a cramped, roughly 12-square-foot (1 square meter) room in a turret inside London's St Mary's Hospital. The famously untidy scientist would culture bacteria from infected hospital patients; he would leave those cultures around for two or three weeks until his bench was crammed with 40 to 50 plates. Then, he would inspect each plate to see if anything interesting had grown in it, before tossing it out.

The discovery of penicillin occurred when Fleming returned from a two-week break. He looked at his plates of Staphylococcus aureus that had been cultured from an infected wound. On one of the plates, Fleming noticed a patch of green mold intersecting the golden-yellow bacterial colonies, according to an account from his assistant, V.D. Allison. Near the green patch, the bacteria were translucent, colorless and dead. The substance that killed the bacteria would form the basis of the first antibiotic, though the term wasn't coined until 1941.

"When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn't plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world's first antibiotic, or bacteria killer," Fleming later said. "But I suppose that was exactly what I did."

Fleming determined that the "mold juice" came from a fungal species he eventually identified as Penicillium. When he described the discovery to his fellow doctors at a meeting the next year, he was met with almost total disinterest. Isolating the elusive "mold juice" also proved challenging, so the discovery languished for a decade, Allison wrote in personal recollections.

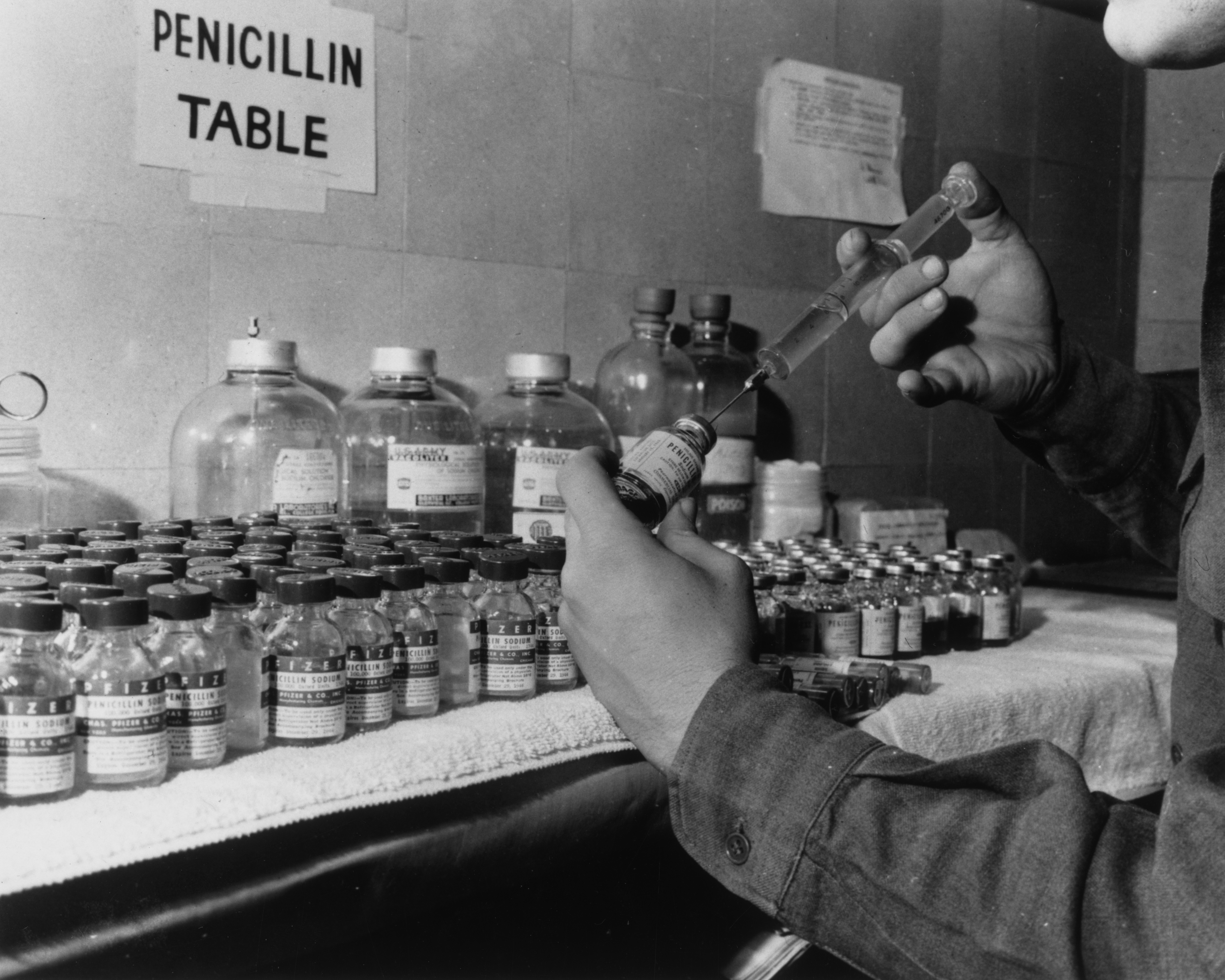

Then, in 1939, scientists Howard Florey and Ernst Chain took an interest in the substance. They created a research team and, along with scientists such as Margaret Jennings, Edward Abraham and Norman Heatley, managed to isolate penicillin from the mold, test it and use the yellowy, powdery substance to cure a handful of patients. However, the compound was still relatively impure.

In 1942, Fleming was treating a young patient who was seriously ill with meningitis. He found the powder killed the patient's bacterial infection, and he phoned Florey and Chain for some of their stash, even though it was not purified. After Fleming injected it into the boy's spinal cord, the patient recovered.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After this miraculous recovery, Fleming was convinced that penicillin needed to be mass-produced. He pitched it to the government, and soon there was a joint effort between the U.S. and the U.K. to mass-produce the substance. By 1945, the first antibiotic was widely available.

Fleming, Florey and Chain would win the 1945 Nobel Prize in medicine for their work on the discovery, isolation and production of penicillin. In 1964, Dorothy Hodgkin would earn the Nobel Prize in chemistry for elucidating its crystal structure, which helped chemists design later antibiotics.

It's estimated that since its discovery, penicillin has saved 500 million lives and, along with its derivatives, is still a mainstay in the treatment of myriad illnesses, including ear infections, strep throat, and urinary tract infections.

Penicillin also led to the development of hundreds of different antibiotics. But widespread use and misuse of these wonder drugs have meant that many bacterial strains have evolved resistance against common antibiotics, including penicillin. In the arms race against superbugs, scientists are now finding totally new ways to fight bacteria, from harnessing the power of viruses to attack bacteria to using the gene-editing tool CRISPR to design new drugs.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus