Rare 'stiff person syndrome' treated with reconfigured cancer therapy

A case study shows how a therapy typically used for cancer could be adapted to treat a disorder that Céline Dion recently disclosed she has.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Stiff person syndrome — a rare, progressive disorder that causes painful muscle spasms — can be treated with a therapy typically used for cancer, a new case report suggests.

In stiff person syndrome (SPS), the immune system attacks a key protein in the nervous system. The condition is rare, affecting fewer than 5,000 people in the U.S., but it recently gained attention when Canadian singer Céline Dion announced she had SPS.

Those most severely affected by SPS develop progressively worse muscle stiffness, eventually leaving them bedbound, while chest spasms can sometimes hinder their breathing. There is currently no cure for SPS, only treatments to subdue the symptoms — but these don't always help.

Now, a case study published in June in the journal PNAS highlights a potential new treatment for people with SPS.

Related: Women have 4 times men's rate of autoimmune disease. The X chromosome may be to blame.

One of the greatest challenges people with SPS deal with is getting a diagnosis, because the disease is rare and its symptoms resemble those of other disorders. In 2014, Dr. Simon Faissner, a neurologist in the St. Josef Hospital at the Ruhr University of Bochum, met the patient featured in the case report. She reported stiffness and pain when moving, but her case notes said that previous physicians thought her symptoms were psychosomatic — brought on by a psychological condition.

Faissner performed a lumbar puncture test, revealing that the patient's cerebrospinal fluid, which circulates through the spinal cord and the brain, was packed with antibodies against a protein called glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). GAD is needed to make GABA, a chemical messenger that helps tamp down neuron activity. Without it, the brain fires off signals at an excessive rate, leading to the muscle cramps and stiffness seen in SPS.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Following her diagnosis, the patient started therapies that dampened these GAD-targeting antibodies and stabilized her condition for several years. However, by 2023, her condition had deteriorated, leaving her unable to walk for a time.

To try and alleviate some of the patient's symptoms, Faissner and Dr. Jeremias Motte, another St. Josef Hospital neurologist, decided to use a new treatment: an adapted CAR T-cell therapy.

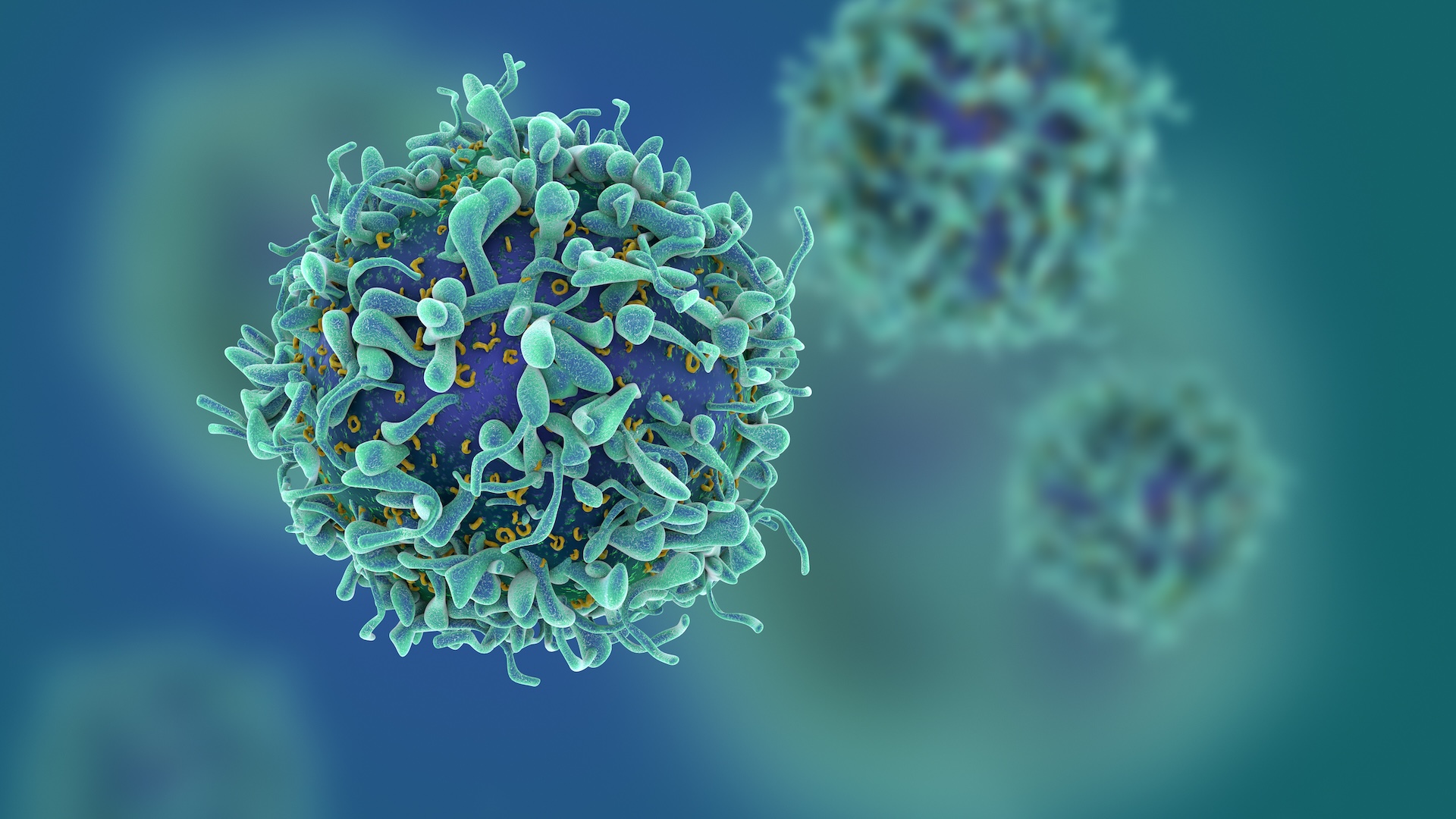

This treatment uses immune cells called T cells, which hunt down and kill abnormal and diseased cells in the body. The therapy involves removing some of a patient's T cells and tweaking them to take aim at a specific target — typically cancer.

However, in the new case report, the researchers aimed CAR T cells' crosshairs at antibody-producing immune cells, called B cells. This approach had previously been tried as a treatment for an autoimmune condition called lupus nephritis, but Faissner and Motte wanted to see if it could help their SPS patient.

Existing SPS therapies also target B cells but less thoroughly. "It's not such a deep depletion of B-cells," Motte told Live Science. "Not so deep in the lymph nodes and not so deep in the organs, muscles or in the bone marrow."

The idea is that CAR T-cell therapy eliminates the disease-driving B cells but leaves behind a population of "baby B cells," Motte said. These then repopulate the body without making harmful antibodies.

"It's like a rebooting of a computer system," Faissner told Live Science. "The problematic immunological system should be erased [following the therapy]."

The treatment had a rapid effect, the team revealed in the case report. The patient had recovered some ability to walk prior to getting the therapy, and within six months of the one-time treatment, her walking speed doubled. She was still fatigued and stiff, but she went from walking only several yards to around 4 miles (6 kilometers) a day.

The patient was also able to discontinue all other immunotherapies and reduce her use of benzodiazepines, which help make up for lost GABA function.

"It's an impressive improvement," Marinos Dalakas, a neurologist at Thomas Jefferson University who developed one of the first immunotherapies for SPS back in 2001, told Live Science.

Dalakas, who was not involved in the case, pointed out that the new treatment remains experimental. Future trials will have to expand on the limited data offered by a single case study. He also noted that there's a mid-stage clinical trial of a different CAR T-cell therapy for SPS happening, although it will be some time before any results are available.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

RJ Mackenzie is an award-nominated science and health journalist. He has degrees in neuroscience from the University of Edinburgh and the University of Cambridge. He became a writer after deciding that the best way of contributing to science would be from behind a keyboard rather than a lab bench. He has reported on everything from brain-interface technology to shape-shifting materials science, and from the rise of predatory conferencing to the importance of newborn-screening programs. He is a former staff writer of Technology Networks.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus