FDA approves 1st pill made from human poop

The Food and Drug Administration approved the second-ever medical treatment made from donated human feces.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the first pill manufactured from donated human poop, the agency announced Wednesday (April 26). It's the second human poop-derived treatment ever approved; the first was an enema-based treatment cleared for use in December 2022.

Previously, such "fecal microbiota transplants" were considered investigational treatments and were therefore harder for patients to access and often not covered by insurance.

Like the approved enema treatment, the newly approved pill, called Vowst, also contains live bacteria and has been approved for use in people ages 18 and older as a preventive treatment for recurrent infections with the bacterium Clostridioides difficile. Called C. diff for short, this infection is often acquired in health care settings after patients have taken antibiotics for a different infection.

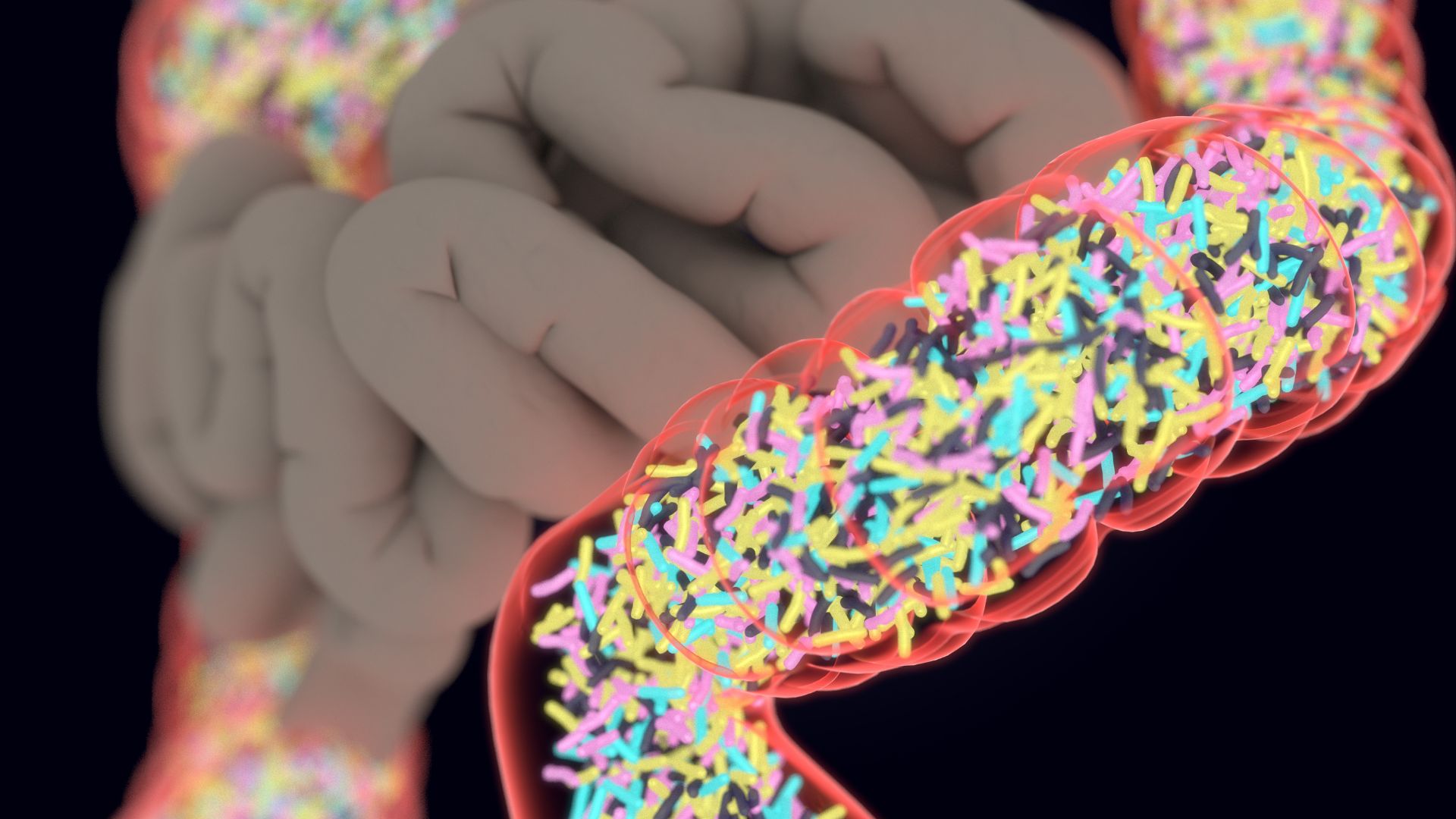

Antibiotics can disrupt the balance of bacteria that normally populate the gut, and this gives C. diff the opportunity to proliferate. The rapidly replicating bacteria secrete toxins that can lead to diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever and colitis (inflammation of the colon) and, in some cases, organ failure and death. C. diff infections are associated with about 15,000 to 30,000 deaths a year in the U.S., according to the FDA.

Related: What is a fecal transplant?

Those who recover from C. diff have a roughly 1 in 6 chance of developing the infection again within two to eight weeks of recovery, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The risk of these recurrent infections increases each time a person gets C. diff, in part because the antibiotics used to treat them further disrupt the gut microbiome, the community of microorganisms in the lower digestive tract.

So-called fecal microbiota products, made from healthy human gut bacteria, offer a new way to prevent recurrent C. diff by essentially replenishing the gut microbiome. And now, with the approval of Vowst, there's a version of the treatment that can be taken orally, rather than being administered as a liquid treatment into a patient's rectum.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The availability of a fecal microbiota product that can be taken orally is a significant step forward in advancing patient care and accessibility for individuals who have experienced this disease that can be potentially life-threatening," Dr. Peter Marks, director of the FDA's Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in the agency's statement.

The Vowst treatment regimen involves taking four capsules once a day for three days in a row; patients start taking the drug two to four days after finishing a course of antibiotics for C. diff. The donated feces used to make the pills is carefully screened for transmissible pathogens before being used in manufacturing, but taking Vowst still carries some risk of being exposed to pathogens, as well as to food allergens, the FDA cautioned.

In clinical trials, the most common side effects of Vowst were abdominal bloating, fatigue, constipation, chills and diarrhea; these side effects occurred at a greater frequency in the treated patients than in the placebo recipients.

In a comparison of about 90 people who received the pills and 90 who didn't, those in the treated group had a 12.4% rate of recurrent C.diff infection within eight weeks of recovering from an initial bout of the infection, whereas the untreated group had a 39.8% rate of recurrence.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus