Baby is born alive after growing in mother's abdomen for 29 weeks

Most ectopic pregnancies, in which a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus, take place in a fallopian tube, but in a rare case, a woman experienced one in her abdomen.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A woman in France went to the hospital with abdominal pain but soon learned that she was in the second trimester of a rare ectopic pregnancy, in which the fetus was growing in her abdomen.

Ectopic pregnancy refers to a phenomenon in which a fertilized egg implants somewhere other than within the uterus, and it occurs in around 2% of pregnancies. Ectopic pregnancies are most likely to occur in the fallopian tubes, the pair of ducts through which eggs travel from the ovaries to the uterus. However, around 1% of ectopic pregnancies occur within the abdominal cavity.

Ectopic pregnancies can't be carried to full term and they cannot be transplanted into the womb. If not treated promptly, they can lead to life-threatening bleeding and infection.

The woman in the new case, described in a report published online on Dec. 9 in The New England Journal of Medicine, had been experiencing abdominal pain for 10 days before she sought medical attention at an emergency department. After physically examining her, doctors suspected she was carrying a baby in her abdomen.

Related: Cannabis use in pregnancy linked to small birth size, other poor outcomes

Before this latest pregnancy, the woman had delivered two babies at full term and experienced one miscarriage.

An ultrasound showed that the lining of her uterus had thickened, which usually happens during the menstrual cycle as the body prepares for a potential pregnancy and then continues during pregnancy. However, there was no fetus within the uterus. Instead, the fetus had been growing in her abdomen for 23 weeks, the doctors determined.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

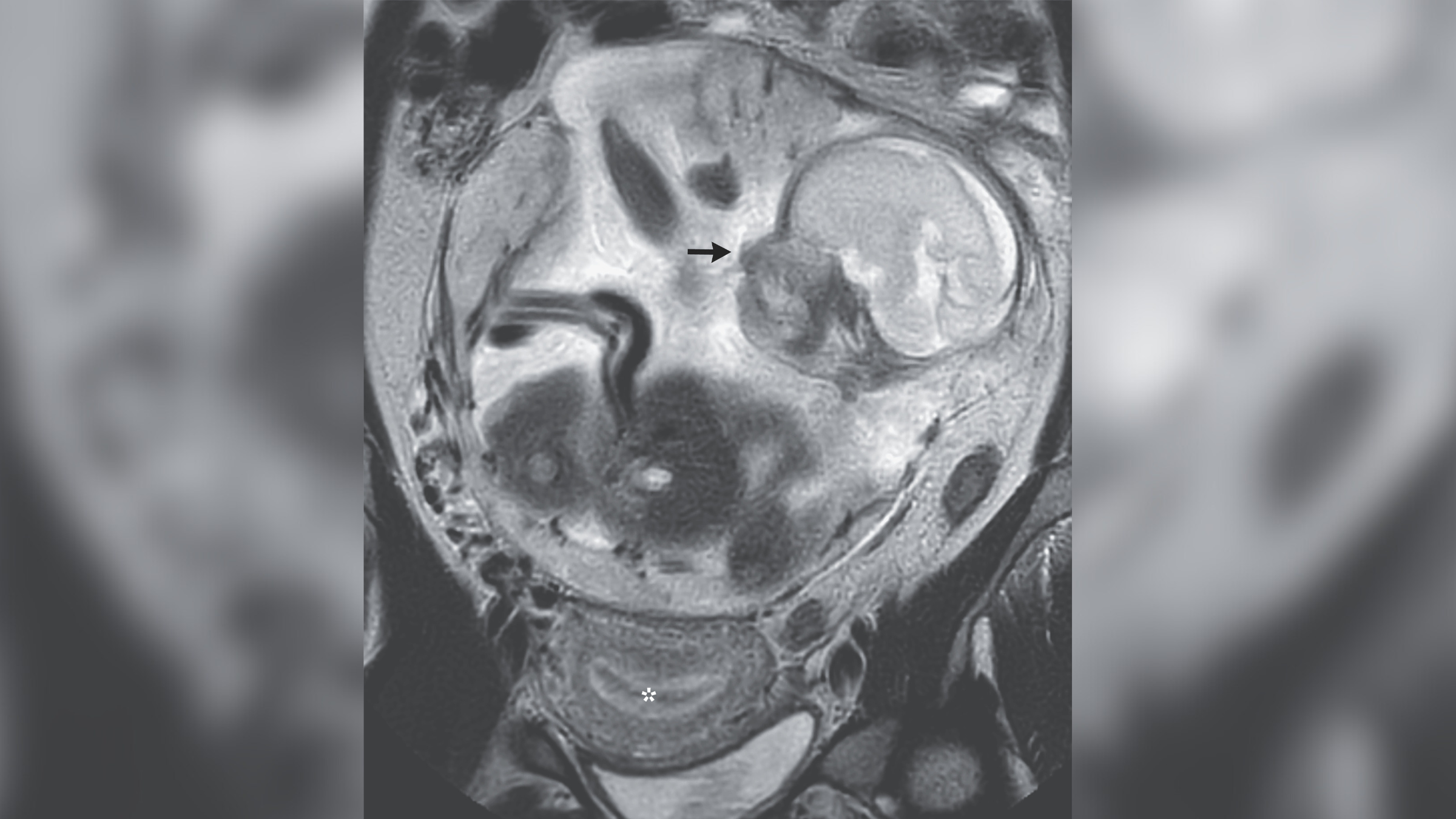

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed that the baby was "normally formed" and was attached to a placenta — the blood-vessel-rich organ that provides nutrients to the developing fetus and normally removes waste from the womb. The placenta was attached to the lining of the abdomen above a bone at the base of the woman's spine.

Ectopic pregnancies can't be carried to full term, which is around 37 to 41 weeks in humans, because the fetus is not supported by the right tissues and it doesn't have enough space to grow. These pregnancies are also extremely risky for the pregnant person as a malpositioned egg may rupture the organ it is implanted in, triggering heavy bleeding and possible infection. The standard treatment is to remove the pregnancy through surgery or to use drugs that stop it from growing.

Due to what the case report authors described as a "high risk of maternal hemorrhage and fetal demise," the woman was transferred to a tertiary care hospital where she could be carefully monitored throughout her final weeks of pregnancy.

Six weeks later, in a procedure called laparotomy, surgeons cut open the woman's abdomen and delivered her baby, who was then immediately transferred to a neonatal intensive care unit. Premature babies, meaning those who are born before 37 weeks, require specialized support as they haven't had as much time to develop inside the body during pregnancy. That said, between 80% and 90% of babies who are born beyond 28 weeks survive.

Part of the placenta was removed in this initial surgery, and the rest was removed in a second procedure. Twenty-five days after the birth, the woman was discharged from the hospital, and around a month after that, she was able to bring the baby home.

The case report authors noted that she was then "lost to follow-up," so the doctors don't know what happened to her and the baby after that.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking NCTJ journalism training with News Associates. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus