Watch thousands of fire ants form living 'conveyor belts' to escape floods (Video)

These buoyant rafts are made of tightly packed ants numbering in the tens of thousands.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

It takes a lot of teamwork to survive floods, and fire ants cooperate in the tens of thousands to build rafts of their bodies to float until the water subsides. Now, a time-lapse video shows how these crafty insects also create living conveyor belts on these rafts to help the riders reach dry land.

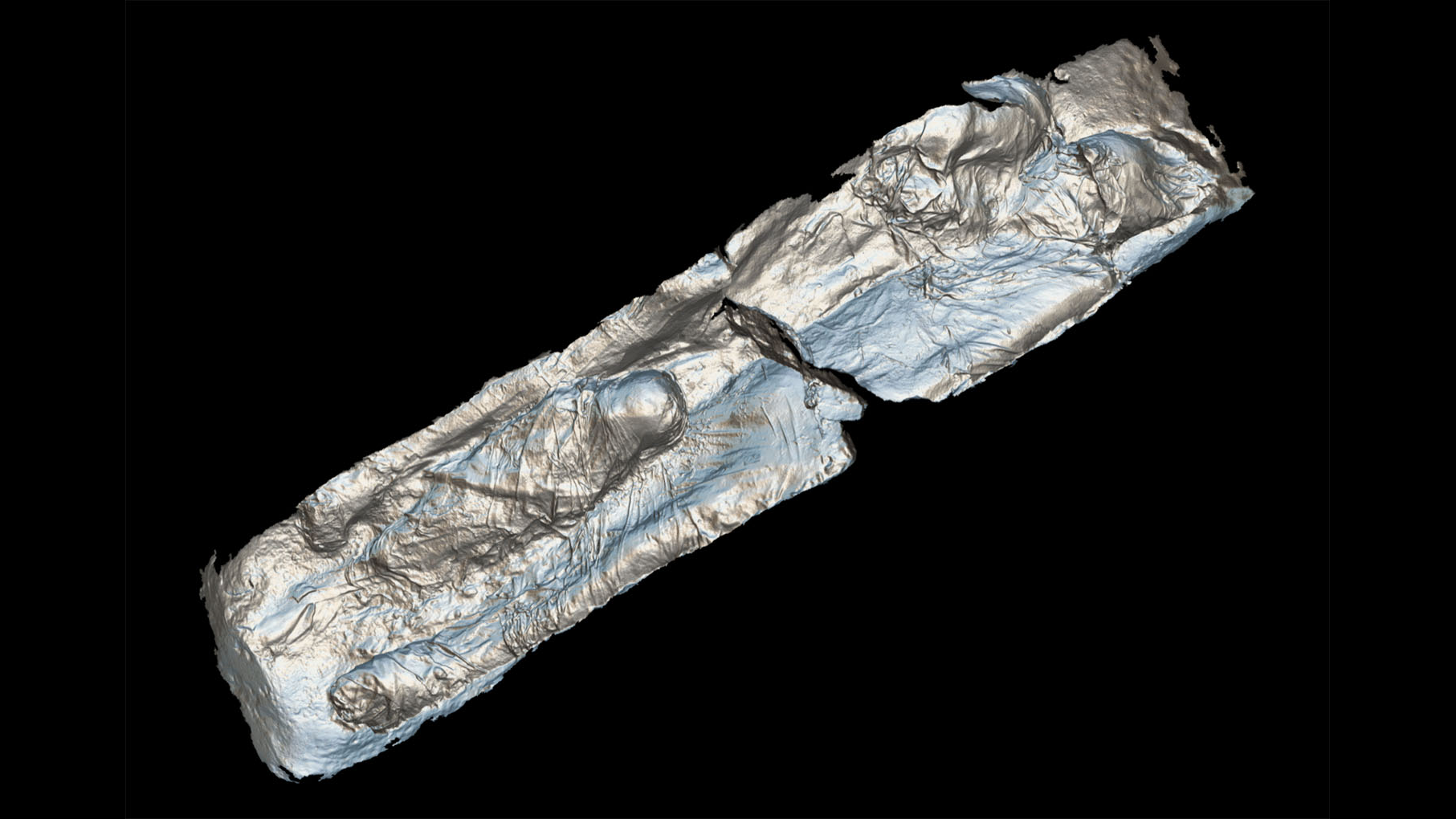

The footage revealed how ant rafts changed their shape, with slender extensions of ants growing from the main sections of ant rafts like tentacles, over just a few hours. These bridges grew from the combined activity of two ant groups: so-called structural ants — insects that pack closely together to keep the colony afloat — that circulated to the top of the pile from the bottom, and surface ants that marched freely about on top of the rafts, which then moved into supporting positions underneath their friends and relatives.

Related: Image gallery: Ants of the world

There are more than 20 species of fire ants worldwide, but one species in particular, the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta), is known for its massive colonies of as many as 300,000 workers, according to North Carolina State University.

If their underground tunnels flood, fire ants link together to create floating rafts that can hold together for weeks, if necessary, carrying the colony until waters recede. A fire ant's exoskeleton naturally repels water, and its rough texture traps air bubbles. Tightly knit ant bodies can, therefore, create a buoyant, water-resistant foundation for a floating raft, Live Science previously reported.

Vast fire-ant rafts were numerous in southern Texas in the wake of 2017's record-breaking Hurricane Harvey. People who were also fleeing the storm's floodwaters were advised to steer clear of the rafts, as fire ants' venomous bites are extremely painful, Live Science reported that year.

Prior research found that even after an ant raft's structure stabilized, its shape continued to change, with questing tentacles extending in multiple directions — but scientists didn't know how, exactly, that was happening.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These protrusions have, to our knowledge, neither been documented nor explained in the existing literature," researchers wrote in a new study, published June 30 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

They collected around 3,000 to 10,000 fire ants at a time and deposited the insects in containers of water with a rod in the center, around which the ants congregated and formed rafts. The scientists then filmed the ant rafts, capturing time-lapse and real-time footage of raft formation and shape changing. Image-tracking data and computer modeling revealed which parts of the ant raft were static and which parts were moving — and where all of the ants in the raft's different layers were going.

The study authors found that the raft's exploratory tentacles were shaped by ant movement that the study authors called "treadmilling." As structural ants wriggled to the surface of the raft, free-walking ants would burrow into the lower structural levels. Together, this cycle contracted and expanded the raft, crafting narrow bridges of ants reaching outward to search for land nearby where the colony could safely disperse.

Other factors — such as the season, time of day and the colony's habitat — can influence ant behavior and could also play a role in the dynamics that shape fire ants' rafts. Those variables weren't explored in the experiments, but they could be investigated in future studies, the scientists concluded.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus