240 million-year-old 'crocodile beast' was one of the largest of its kind

It was an apex predator during the Triassic period.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 240 million years ago, a fearsome archosaur with "very powerful jaws and large knife-like teeth" stalked what is now Tanzania, a new study finds.

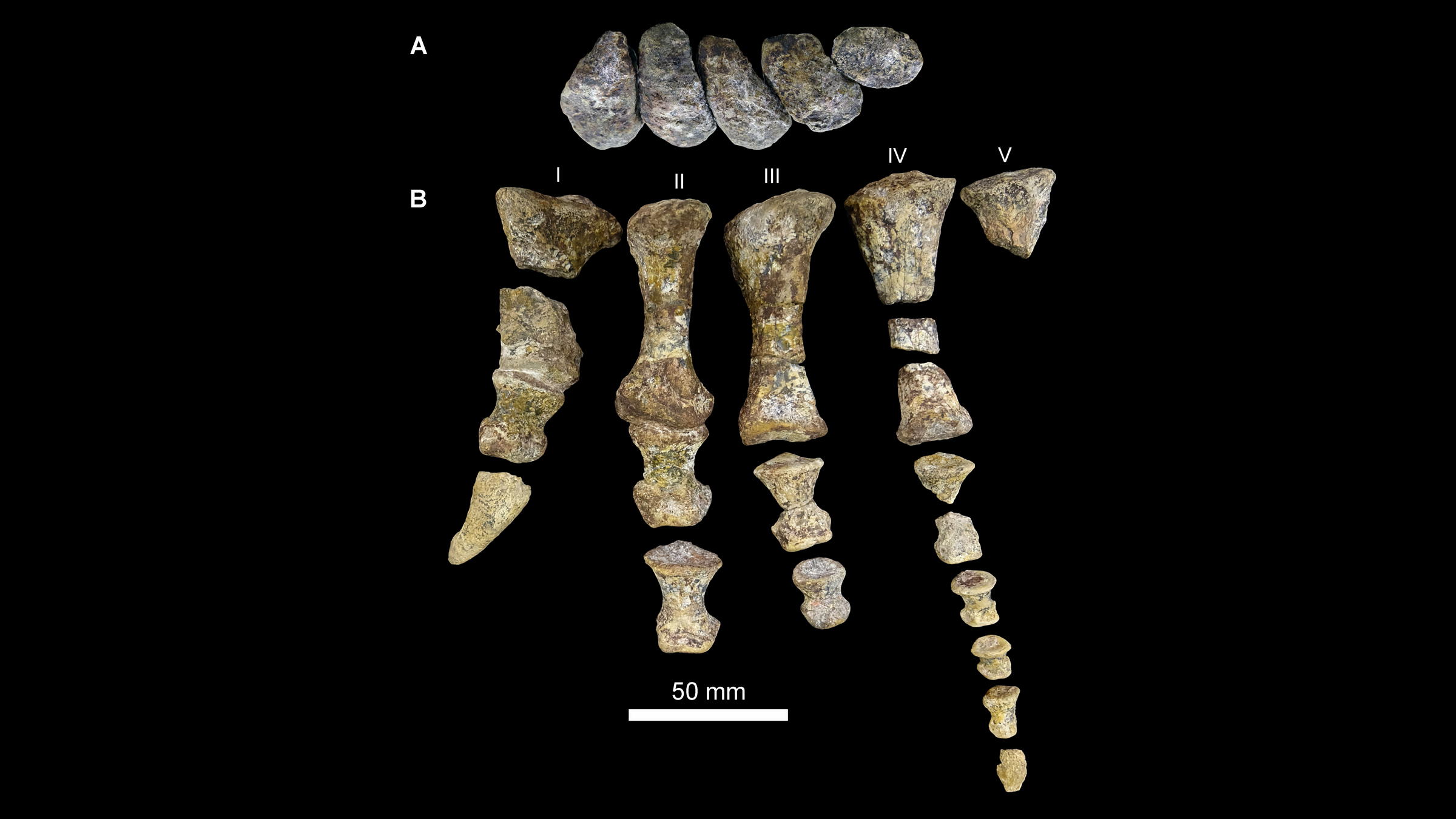

Measuring more than 16 feet (5 meters) long from snout to tail, this newly described beast — called Mambawakale ruhuhu, which means "ancient crocodile from the Ruhuhu Basin" in Kiswahili — "would have been a very large and pretty terrifying predator," when it was alive during the Triassic period, said study lead researcher Richard Butler, a professor of paleobiology at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom.

This apex predator "walked on all fours with a long tail," Butler told Live Science in an email. "It's one of the largest predators that we know of from the Middle Triassic [247 million to 237 million years ago]," or around the same time that the first dinosaurs emerged.

Related: Photos: Early Dinosaur Cousin Looked Like a Croc

It took paleontologists nearly 60 years to properly describe M. ruhuhu. Its fossils were discovered in 1963, a mere two years after Tanzania gained its independence from Britain. During the expedition, scientists, largely from the U.K., heavily relied on Tanzanians and Zambians to find fossil hotspots, discover the fossils, build roads to the site and transport the fossils from the field, according to the study. However, the Tanzanian and Zambian involvement ended there; the fossils were taken from Ruhuhu Basin in southwest Tanzania to the Natural History Museum in London, where they awaited analysis.

One specimen — a beast with a 2.5-foot-long (75 centimeters) skull, as well as a preserved lower jawbone and a fairly complete left hand — was dubbed Pallisteria angustimentum by English paleontologist Alan Charig (1927-1997), who helped collect the creature's remains. But Charig, who named the Triassic terror's genus after his friend, geologist John Weaver Pallister, and its species name with the Latin words for "narrow chin," never formally published a description of the animal. So, when Butler and his colleagues examined the specimen decades later, they chose a Kiswahili name "to formally recognize the substantial and previously unsung contributions of unnamed Tanzanians" on the 1963 expedition, the researchers wrote in the study.

"Our key results are the formal recognition of Mambawakale as a new species for the first time," said Butler, who along with John Lyakurwa, a Tanzanian neoherpetologist at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, helped name the archosaur.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

M. ruhuhu is one of the largest known early archosaurs, a group that emerged following the end-Permian extinction about 252 million years ago. The archosaur clade includes living birds and crocodilians, as well as the extinct pterosaurs and nonavian dinosaurs. When M. ruhuhu was alive during the Middle Triassic, archosaurs "really start to diversify for the first time," Butler said.

For example, M. ruhuhu is just one of nine ancient archosaur species discovered at the Tanzania site. "Mambawakale adds to this picture of a rapid early diversification of archosaurs and moreover was the largest predator within its ecosystem," Butler said.

The study was published online Wednesday (Feb. 9) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus