Maya nobility performed bloodletting sacrifices to strengthen a 'dying' sun god during solar eclipses

The Maya created a complex calendar system to regulate their world — one of the most accurate of pre-modern times.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

We live in a light-polluted world, where streetlamps, electronic ads and even backyard lighting block out all but the brightest celestial objects in the night sky. But travel to an officially protected "Dark Sky" area, gaze skyward and be amazed.

This is the view of the heavens people had for millennia. Pre-modern societies watched the sky and created cosmographies, maps of the skies that provided information for calendars and agricultural cycles. They also created cosmologies, which, in the original use of the word, were religious beliefs to explain the universe. The gods and the heavens were inseparable.

The skies are orderly and cyclical in nature, so watch and record long enough and you will determine their rhythms. Many societies were able to accurately predict lunar eclipses, and some could also predict solar eclipses — like the one that will occur over North America on April 8, 2024.

The path of totality, where the Moon will entirely block the Sun, will cross into Mexico on the Pacific coast before entering the United States in Texas, where I teach the history of technology and science, and will be seen as a partial eclipse across the lands of the ancient Maya. This follows the October 2023 annular eclipse, when it was possible to observe the "ring of fire" around the Sun from many ancient Maya ruins and parts of Texas.

A millennia ago, two such solar eclipses over the same area within six months would have seen Maya astronomers, priests and rulers leap into a frenzy of activity. I have seen a similar frenzy — albeit for different reasons — here in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, where we will be in the path of totality. During this period between the two eclipses, I have felt privileged to share my interest in the history of astronomy with students and the community.

Ancient astronomers

The ancient Maya were arguably one of the greatest sky-watching

societies. Accomplished mathematicians, they recorded systematic observations on the motion of the Sun, planets and stars.

From these observations, they created a complex calendar system to regulate their world — one of the most accurate of pre-modern times.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Astronomers closely observed the Sun and aligned monumental structures, such as pyramids, to track solstices and equinoxes. They also utilized these structures, as well as caves and wells, to mark the zenith days — the two times a year in the tropics where the Sun is directly overhead and vertical objects cast no shadow.

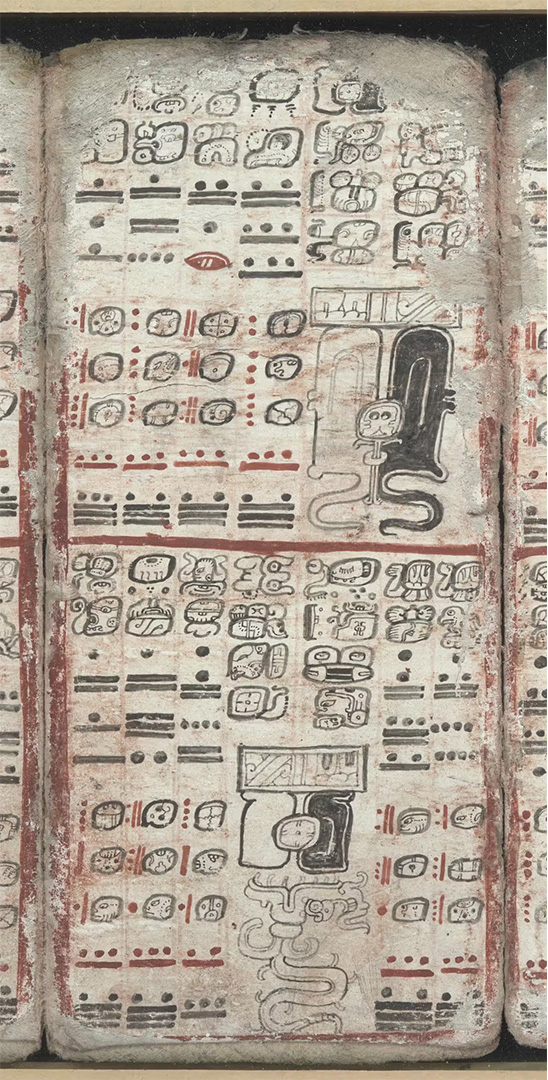

Maya scribes kept accounts of the astronomical observations in codices, hieroglyphic folding books made from fig bark paper. The Dresden Codex, one of the four remaining ancient Maya texts, dates to the 11th century. Its pages contain a wealth of astronomical knowledge and religious interpretations and provide evidence that the Maya could predict solar eclipses.

From the codex's astronomical tables, researchers know that the Maya tracked the lunar nodes, the two points where the orbit of the Moon intersects with the ecliptic — the plane of the Earth's orbit around the Sun, which from our point of view is the path of the Sun through our sky. They also created tables divided into the 177-day solar eclipse seasons, marking days where eclipses were possible.

Heavenly battle

But why invest so much in tracking the skies?

Knowledge is power. If you kept accounts of what happened at the time of certain celestial events, you could be forewarned and take proper precautions when cycles repeated themselves. Priests and rulers would know how to act, which rituals to perform and which sacrifices to make to the gods to guarantee that the cycles of destruction, rebirth and renewal continued.

In the Maya's belief system, sunsets were associated with death and decay. Every evening the sun god, Kinich Ahau, made the perilous journey through Xibalba, the Maya underworld, to be born anew at sunrise. Solar eclipses were seen as a "broken sun" — a sign of possible cataclysmic destruction.

Kinich Ahau was associated with prosperity and good order. His brother Chak Ek – the morning star, which we now know as the planet Venus — was associated with war and discord. They had an adversarial relationship, fighting for supremacy.

Their battle could be witnessed in the heavens. During solar eclipses, planets, stars and sometimes comets can be seen during totality. If positioned properly, Venus will shine brightly near the eclipsed Sun, which the Maya interpreted as Chak Ek on the attack. This is hinted at in the Dresden Codex, where a diving Venus god appears in the solar eclipse tables, and in the coordination of solar eclipses with the Venus cycles in the Madrid Codex, another Maya folding book from the late 15th century.

With Kinich Ahau — the Sun — hidden behind the Moon, the Maya believed he was dying. Renewal rituals were necessary to restore balance and set him back on his proper course.

Nobility, especially the king, would perform bloodletting sacrifices, piercing their bodies and collecting the blood drops to burn as offerings to the sun god. This "blood of kings" was the highest form of sacrifice, meant to strengthen Kinich Ahau. Maya believed the creator gods had given their blood and mixed it with maize dough to create the first humans. In turn, the nobility gave a small portion of their own life force to nourish the gods.

Time stands still

In the lead-up to April's eclipse, I feel as if I am completing a personal cycle of my own, bringing me back to earlier career paths: first as an aerospace engineer who loved her orbital mechanics classes and enjoyed backyard astronomy; and then as a history doctoral student, studying how Maya culture persisted after the Spanish conquest.

For me, just like the ancient Maya, the total solar eclipse will be a chance to not only look up but also to consider both past and future. Viewing the eclipse is something our ancestors have done since time immemorial and will do far into the future. It is awesome in the original sense of the word: For a few moments it seems as if time both stops, as all eyes turn skyward, and converges, as we take part in the same spectacle as our ancestors and descendants.

And whether you believe in divine messages, battles between Venus and the Sun, or in the beauty of science and the natural world, this event brings people together. It is humbling, and it is also very, very cool.

I just hope that Kinich Ahau will grace us with his presence in a cloudless sky and once again vanquish Venus, which is a morning star on April 8.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Kimberly Breuer is an Associate Professor of Instruction in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Arlington, where she teaches courses in the history of science and technology and Iberian history and conducts research on teaching and learning. She holds a Ph.D. in history from Vanderbilt University, specializing in Latin American and Native American history in the late medieval and early modern eras. She also earned a BS in Aerospace Engineering and worked in the aircraft industry for several years.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus