'Zeus made night from mid-day': Terror and wonder in ancient accounts of solar eclipses

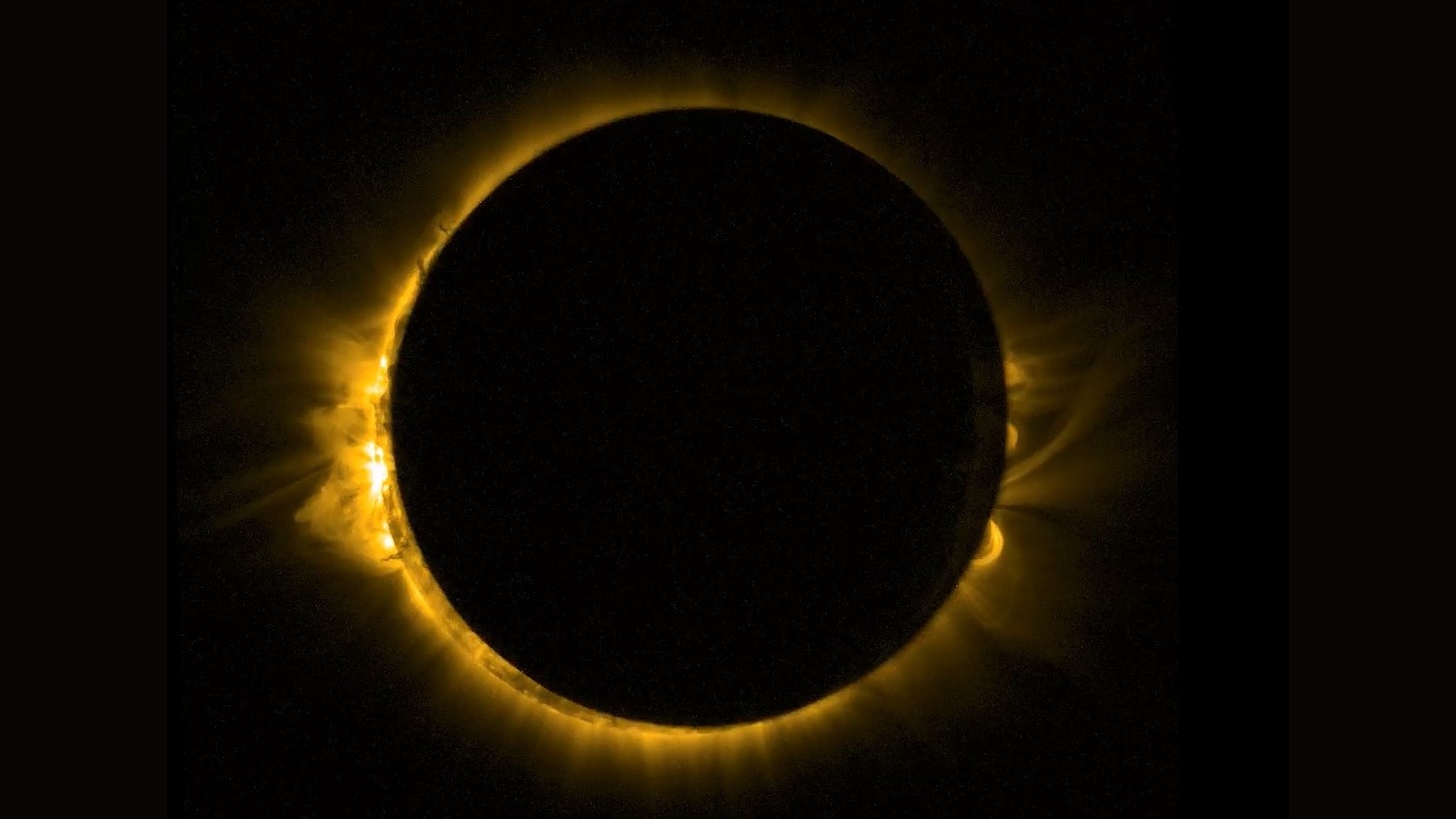

For millennia, solar eclipses like the upcoming one on April 8 have inspired awe, wonder and fear. Here are some of the most intriguing accounts of solar eclipses from ancient Greece to the Mayan empire.

For millennia, solar eclipses have inspired awe, wonder and fear. After all, it's not often that twilight descends in the middle of the day. And just as we plan for and anticipate their occurrence — like the total solar eclipse that will be visible to millions of North Americans on April 8 — ancient cultures across the world, from the Mayans to the ancient Greeks, developed their own mythologies and traditions around eclipses.

So what did these people think when they saw the sun darkening during the day?

On a surface level, people from ancient cultures knew exactly what they were looking at. "Anybody who pays attention to the sky would be well aware that the moon is blocking the sun," Anthony Aveni, a professor of anthropology and astronomy at Colgate University in New York, told Live Science. But the significance of that event would have been very different to ancient peoples. "Cultures other than our own, both present and past, had a very different take on the natural world," Aveni added.

Many ancient cultures believed what happened in the skies reflected past, present and future events on Earth. That was particularly true for the Maya — a civilization that reached its peak in Central America during the first millennium A.D. and whose descendants live throughout the world today. The ancient Maya viewed distance in space and distance in time as one in the same, explained Aveni. In other words, gazing far into the cosmos acted as a kind of portal to the past.

Related: How often do solar eclipses occur?

When the ancient Mayans viewed eclipses, they saw what looked like the moon eating the sun, Aveni said. They interpreted that as a view into the cannibalistic practices of their ancestors, which had long since been eliminated by Mayan laws. "So for the Maya, the eclipse, which happens in cosmic space, becomes a reminder that the social order is always in danger of getting out of balance," Aveni explained in a recent talk at Colgate University's Ho Tung Visualization Lab.

The Maya weren't the only people who thought they saw the sun being eaten. In ancient Chinese mythology, solar eclipses occurred when a dragon tried to devour the sun. In response, people would crowd into the streets, banging drums to scare the dragon away, according to NASA. One ancient Chinese record — likely referring to a solar eclipse that occurred in 2134 B.C. — reported that "the sun and the Moon did not meet harmoniously." According to NASA, the cacophony on the streets alerted the emperor to what was happening up above. Incensed that the two court astronomers had failed to predict the event, he had them both beheaded.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the ancient Greeks, eclipses were a sign of the gods' displeasure with humans; in retaliation, the sun would abandon Earth. The word eclipse actually comes from the Greek word "ekleipsis," meaning "abandonment" or "a forsaking," according to Merriam-Webster. In response to a solar eclipse in 647 B.C., the poet Archilochus wrote: "There is nothing beyond hope, nothing that can be sworn impossible, nothing wonderful, since Zeus, father of the Olympians, made night from mid-day, hiding the light of the shining Sun, and sore fear came upon men."

Modern science helps us understand how and when eclipses occur, but ancient cultures approached the cosmos with a fundamentally different lens than us. They were turning to nature to understand human society. "What's nonsense to you, may not be nonsense to another culture," Aveni said.

And in many ways, our reactions today may not be so different. Even today, Aveni sees people respond to eclipses with a mix of wonder and fear: "Fear because this is something extraordinary — this weird twilight in the daytime."

Isobel Whitcomb is a contributing writer for Live Science who covers the environment, animals and health. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fatherly, Atlas Obscura, Hakai Magazine and Scholastic's Science World Magazine. Isobel's roots are in science. She studied biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, while working in two different labs and completing a fellowship at Crater Lake National Park. She completed her master's degree in journalism at NYU's Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus