Stars, planets and more will be visible during the total solar eclipse on April 8. Here's what to look for, and where.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

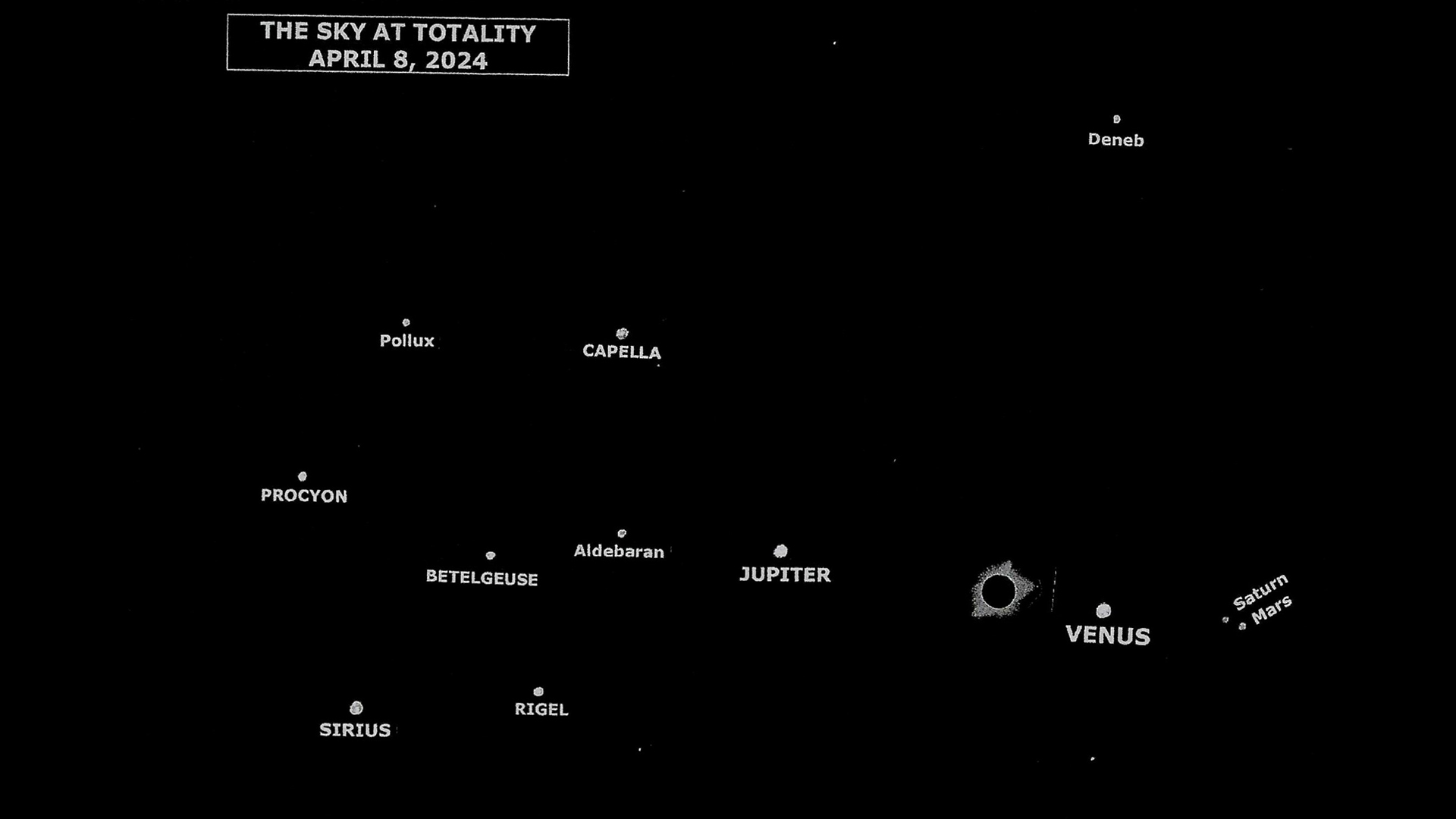

An observer in or near the path of totality for the April 8 solar eclipse may be witness to many unusual phenomena, including the appearance of the moon's shadow projected on the Earth's atmosphere, and darkness during the daytime.

For the upcoming eclipse, a few minutes before the start of totality, a conspicuous shadow should appear, mimicking an approaching storm, moving from the west-southwest sky and toward the observer. Darkness will follow, and with it the chance to see stars, planets and possibly other bright objects in the daytime sky.

Here's what to look for during totality, and where in the sky to look.

Related: April 8 solar eclipse: What time does totality start in every state?

Exotic colors and lighting

I've often been asked, why bother traveling to an eclipse? My answer is always the same: "You must see one for yourself, and then you will understand." Astronomy writer Guy Ottewell planned to create a painting of the 1983 eclipse visible from Borobudur in Java. He later wrote in his book, "The Under-Standing of Eclipses:

"During the minutes of totality, I was conscious of being in a different visual world; of trying to memorize colors for which I had no names, which would be as hard to recall or describe as a taste."

For those witnessing the total phase, the moon's shadow overhead appears a dusky blue (if there are no clouds), and the light from outside its edge forms a bright border around the horizon. The saffron tint of air outside an eclipse shadow may be especially impressive. Since air scatters long wavelengths of light less than short, the light from outside the shadow is yellowed or reddened, the exact color depending on the distance from the shadow edge to the observer.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At 50 miles or more, the bright reddening glow is pronounced and the bright tawny glow is low. Since at the upcoming eclipse, one can be as far as 50 to 60 miles (80 to 100 kilometers) from the shadow's edge — if positioned on the center line of the eclipse path — some vivid colorations may be evident, especially toward the northwest and southeast at mid-totality.

A view from the outside the path of totality

Outside the path of totality, even at a considerable distance, the moon's shadow can sometimes be seen projected against the atmosphere. At the eclipse of July 9, 1945, the shadow was seen near the horizon from Portland, Oregon, 320 miles (515 km) west of the point where the eclipse was first total at sunrise. Also, at the eclipse of October 2, 1959, which was total in eastern Massachusetts, the shadow was visible on the northeastern horizon to an observer only 15 miles (24 km) northeast of New York City. The smaller the distance from the path of totality, the better the chance of seeing the shadow.

There are several methods of observing the degree of darkness at mid-eclipse. One way is to note the smallest size of newsprint that is legible. This can be done even when the sky is overcast, but the type and extent of cloud cover should be carefully recorded. Also, useful and even better than visual techniques are good all-sky photographs (using a fish-eye lens or wide-angle convex mirrors), or photometric measurements with photoelectric meters.

A second way is to note the faintest star or planet visible.

Cameo appearance by stars and planets

When the sun is totally eclipsed, the sky does not (as many astronomy guidebooks suggest) appear "as dark as a moonlit night." Rather, it gets about as dark as it is about 20 to 40 minutes before sunrise or 20 to 40 minutes after sunset. In such a sky, Venus is usually very conspicuous, and other bright planets and 1st-magnitude stars near the sun have also been reported.

Venus by far will be the brightest object at visual magnitude -3.9 (in astronomy, the lower the magnitude, the brighter the object). On eclipse day, it will be positioned about 15 degrees to the west (lower right) of the sun. Your clenched fist held at arm's length measures roughly 10 degrees, so Venus will be situated about "one and a half fists" from the sun. Jupiter, second in brightness to Venus at magnitude -2.0, will lie 30 degrees to the east (upper left) of the sun.

There will be other planets around, but it's debatable whether they will be readily visible. Saturn (magnitude +1.1) and Mars (magnitude +1.2) will be, respectively, 35 and 36-degrees to the west of the sun. Little Mercury will stand a half-dozen degrees to the east of the sun, but at a very faint magnitude +4.3, so it will be invisible.

So far as stars are concerned, this eclipse will give you a fine opportunity to gauge the brightness of the sky since the bright stars of the winter season will be well-placed across much of the eastern part of the sky. Low toward the east-southeast is Sirius, the brightest of all stars at magnitude -1.5. If, however, you are located along the totality path in Texas or Mexico, you won't see it because it will be below the horizon.

Capella (magnitude +0.1) will be high in the east-northeast, while Rigel (magnitude +0.2) will be much lower in the southeast. A few fainter stars of the first magnitude may appear here and there, but the light of the corona (the sun's outer atmosphere) as well as the general scattering of light filtering in from outside of the umbra will quench most of the stars.

Then again...

But perhaps using your totality time to try and pick out stars and planets is not the way to go. A well-known aficionado of stars and constellations was George Lovi (1939-1993), who for over two decades wrote the popular "Rambling Through the Skies" column in Sky & Telescope magazine. Mr. Lovi often expounded on the beauty of the totally eclipsed sun as viewed through binoculars or even through a camera's telephoto lens. "The human eye," he wrote, "has an unmatched ability to view subtle details within the inner and outer corona, in a way no emulsion can."

But then he'd also argue about those who engaged themselves in what he referred to as the "sometimes ridiculous efforts" to hunt down stars and planets during the total phase of the eclipse. "Some devotees spend virtually all those precious minutes searching!" he would rant, adding, "I can't for the life of me imagine how this compares to the main event!"

To that end, I would agree with Mr. Lovi (myself having journeyed to 13 total eclipses); you probably would do better to spend a good part of your precious totality time concentrating on viewing the solar corona.

As one person later said to me in the aftermath of spending all of his time trying to unsuccessfully photograph a total eclipse:

"I, therefore, came to the conclusion, and it represents a bit of wisdom, gained at great expense and hardship, which I feel compelled to pass on to other enthusiasts, and that is, the best possible way to see an eclipse is simply LOOK AT IT!"

This might be the best piece of advice for anybody who intends to observe the spectacle of a total eclipse of the sun. So, remember, should you get your chance at one, indeed, just LOOK at it and ENJOY it.

After all, even in 2024, a few minutes of wonder is all you're going to get!

To safely view all of this event, you must use solar filters. Only those in the path of totality will be able to remove them briefly to see the sun's corona with their naked eyes. Those not in the path of totality must keep them on the entire time.

Everyone observing the partial phases of this eclipse — and for those outside the path of totality, that's the entire event — will need to wear solar eclipse glasses while cameras, telescopes and binoculars will need solar filters placed in front of their lenses.

Originally posted on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus