Flesh-eating 'killer' lampreys that lived 160 million years ago unearthed in China

Scientists have described two lamprey fossils with "extensively toothed" mouths from the Jurassic period, shining a light on how this group has evolved into its modern forms since the Devonian.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists in China have unearthed two superbly preserved, 160 million-year-old lamprey fossils — including the largest found to date — shining a light on this group's obscure evolutionary history.

Lampreys are one of two living jawless vertebrate groups that first appear in the fossil record around 360 million years ago, during the Devonian period (419.2 million to 358.9 million years ago). These ancient fish, including 31 species alive today, typically have teeth-filled sucker mouths that they use to latch onto prey to extract blood and other body fluids.

The newly described fossils date to the Jurassic period (201.3 million to 145 million years ago) and bridge a gap between early fossil discoveries and extant lineages. Researchers unearthed the specimens from a fossil bed in northeast China and named them Yanliaomyzon occisor and Y. ingensdentes — their species names meaning "killer" in Latin and "large teeth" in Greek, respectively.

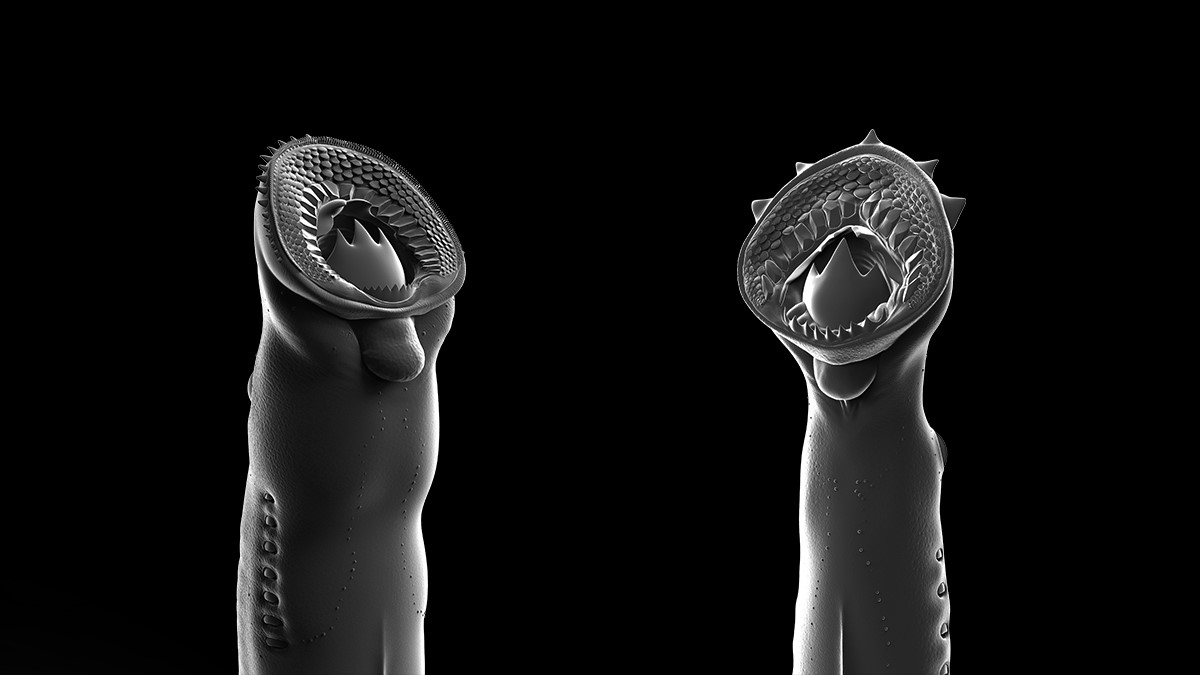

"These fossil lampreys were exquisitely preserved with a complete suite of feeding structures," researchers wrote in a study published Tuesday (Oct. 31) in the journal Nature Communications.

Looking at early fossils, it has long been clear that lampreys have undergone major changes since the Devonian, the authors wrote. But until now, huge gaps in the fossil record meant scientists didn't know when these changes occurred.

Related: Nightmarish deep-sea footballfish washes up on California beach in rare stranding

Y. occisor, the larger of the two newfound fossils, measured 25.3 inches (64.2 centimeters) long and is the largest lamprey fossil ever found, according to the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Living lamprey species can get much bigger than this, however; sea lampreys (Petromyzon marinus) grow up to 4 feet (120 cm) long, and Pacific lampreys (Entosphenus tridentatus) reach up to 2.8 feet (85 cm).

The earliest lampreys, on the other hand, were only a few inches long. They had tiny, simple teeth and likely no anticoagulant-producing glands, which their modern counterparts use to keep their prey's blood flowing. The mouthparts of these early lampreys indicate they weren't predatory or even parasitic, the authors wrote, but instead fed on algae. "Their feeding opportunities were rather limited because the vast majority of their potential hosts then all had thick scales or armor" that they would not have been able to penetrate, the researchers added.

The newly described fossils showed "extensively toothed" mouths, suggesting lampreys were preying on other animals at least 160 million years ago, according to the study. The mouthparts of Y. occisor and Y. ingensdentes also bear a striking resemblance to those of extant pouched lampreys (Geotria australis), pointing to "an ancestral flesh-eating habit for modern lampreys," the authors wrote. This predatory lifestyle likely led to an increase in lampreys' body size by the Jurassic period, they added.

Lampreys also underwent major changes in their life history between the Devonian and the Jurassic, according to the study. The large size of Y. occisor in particular is similar to subsequent species that evolved a three-staged life cycle — comprising a larval, metamorphic and adult stage — indicating it may also have a triphasic cycle and migrated up rivers to spawn.

The discovery fills a gap in the evolutionary history of lampreys, throwing light both on changes in the fishes' feeding habits and on the modernization of their life history during the Jurassic period, according to the study.

"This history can be divided into two episodes linked by the Jurassic species," the authors wrote.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus