Fish sprouted fingers before they ventured onto land, fossil shows

Thank this fish for your fingers.

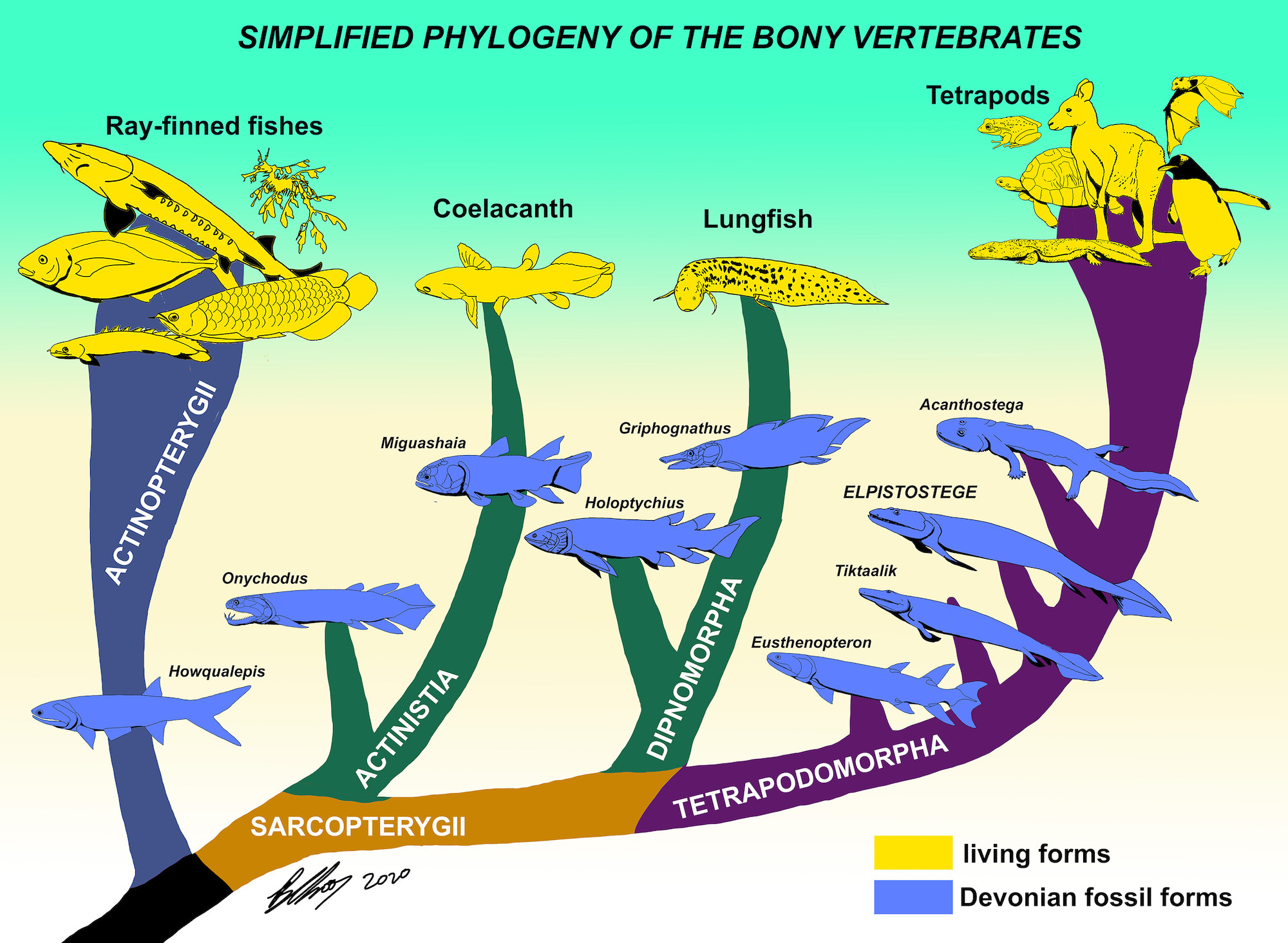

A 380-million-year-old fossil of a fish has revealed that fingers evolved in vertebrates before the creatures wriggled out of the sea and evolved into land-dwelling creatures, as a new study describes.

The fossil of the 5.1-foot-long (1.6 meters) fish, known by the scientific name Elpistostege watsoni, suggests that human hands likely evolved, eventually, from the fins of this fish, said study lead researcher Richard Cloutier, a professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Quebec in Rimouski.

The fossil "clarifies the question about the transition between fish and four-legged animals," known as tetrapods, Cloutier told Live Science in an email. "It is the first time that digits, as seen in tetrapods, are found in a fin covered by scales and fin rays, as seen in fishes."

Related: Images: Weird ancient fish fossil (tiktaalik)

A fossil to remember

The discovery of the fossil, in Miguasha National Park in Quebec, took an entire team. Two tourists found different pieces of the tail, and Benoît Cantin, a Miguasha park warden-naturalist, found the majority of the fossil on the beach, which he excavated with Michel Haché and Philippe Duranleau Gagnon, both naturalist guides at the park.

This group of naturalists unearthed "the longest fossil ever found in the Escuminac Formation, less than 200 meters [656 feet] behind the [park's] museum," Cloutier said. This fossil was a prize: Although broken into 22 slabs of rock, it showed the most complete specimen of E. watsoni to date.

Once the tail pieces found by the tourists were added, "it was the last piece of the puzzle to complete our unique, 1.57-meter-long specimen of Elpistostege, the only complete [fossil of a] elpistostegalian, or tetrapod-like fish, known on Earth," Cloutier said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other elpistostegalian fishes include the Tiktaalik, known only from incomplete fossil specimens in the Canadian Arctic.

Fossil fish gallery

Fish world

When E. watsoni was alive, some 380 million years ago, during the Devonian period, fishes ruled the world. It would be another 150 million years before dinosaurs came into being.

E. watsoni lived in a large estuary along the south coast of Euramerica, an ancient continent that included today's North America and part of Europe. At that time, Euramerica was a little south of the equator, so E. watsoni enjoyed a warm climate.

On land, there were 33-foot-tall (10 m) tree-like ferns, as well as smaller plants. But there weren't any vertebrates, or animals with backbones. Instead, there were invertebrates, such as scorpions and millipedes, Cloutier said. The only vertebrates, like the sharp-fanged E. watsoni, were in the sea.

"Exceptional fossil"

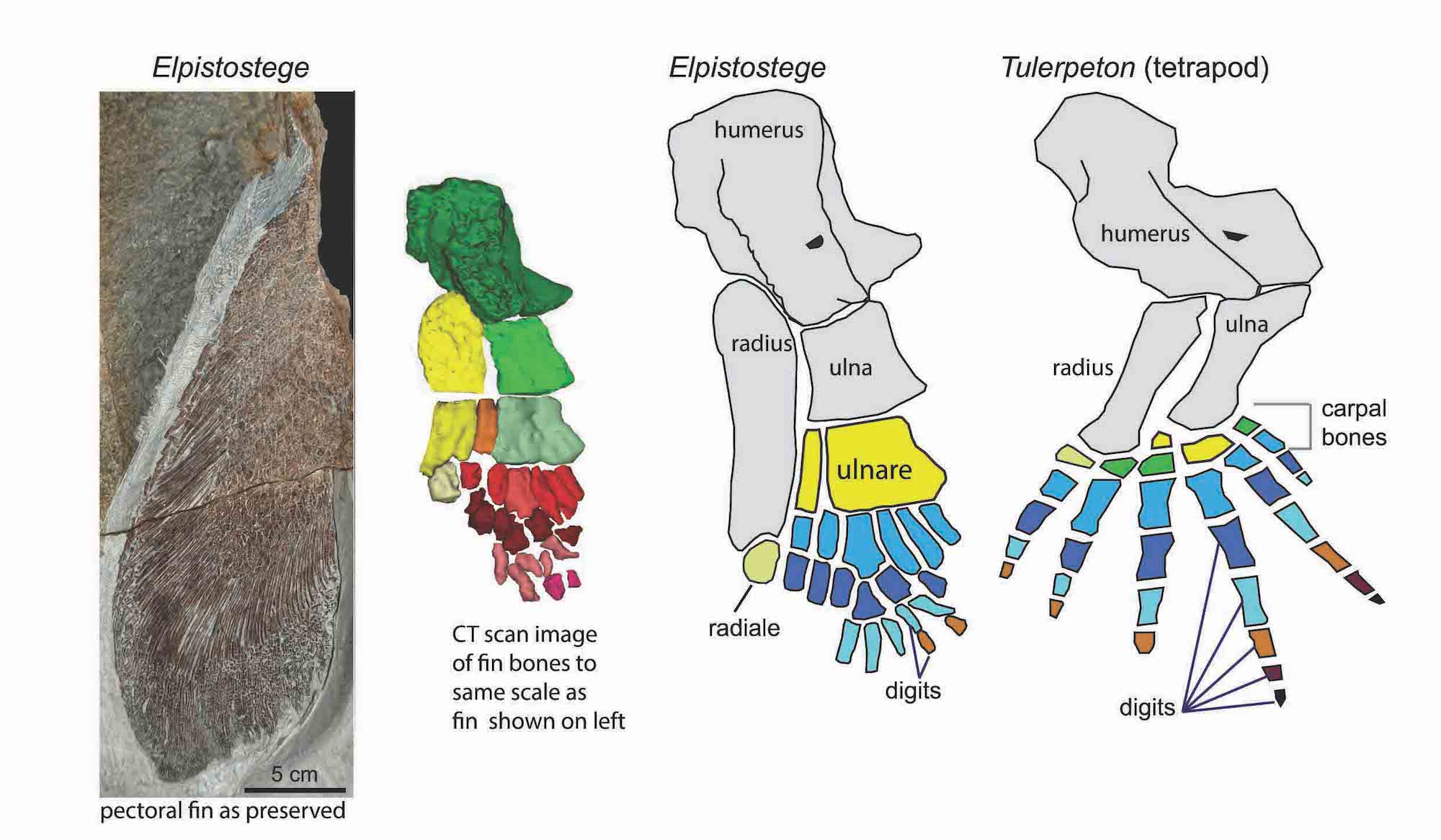

The researchers analyzed the fish via a high-energy CT (computed tomography) scan at The University of Texas at Austin, Cloutier said. This gave the team, composed of scientists from the University of Quebec in Rimouski and Flinders University in Australia, a digital image of the fossil that they could rotate, magnify and study.

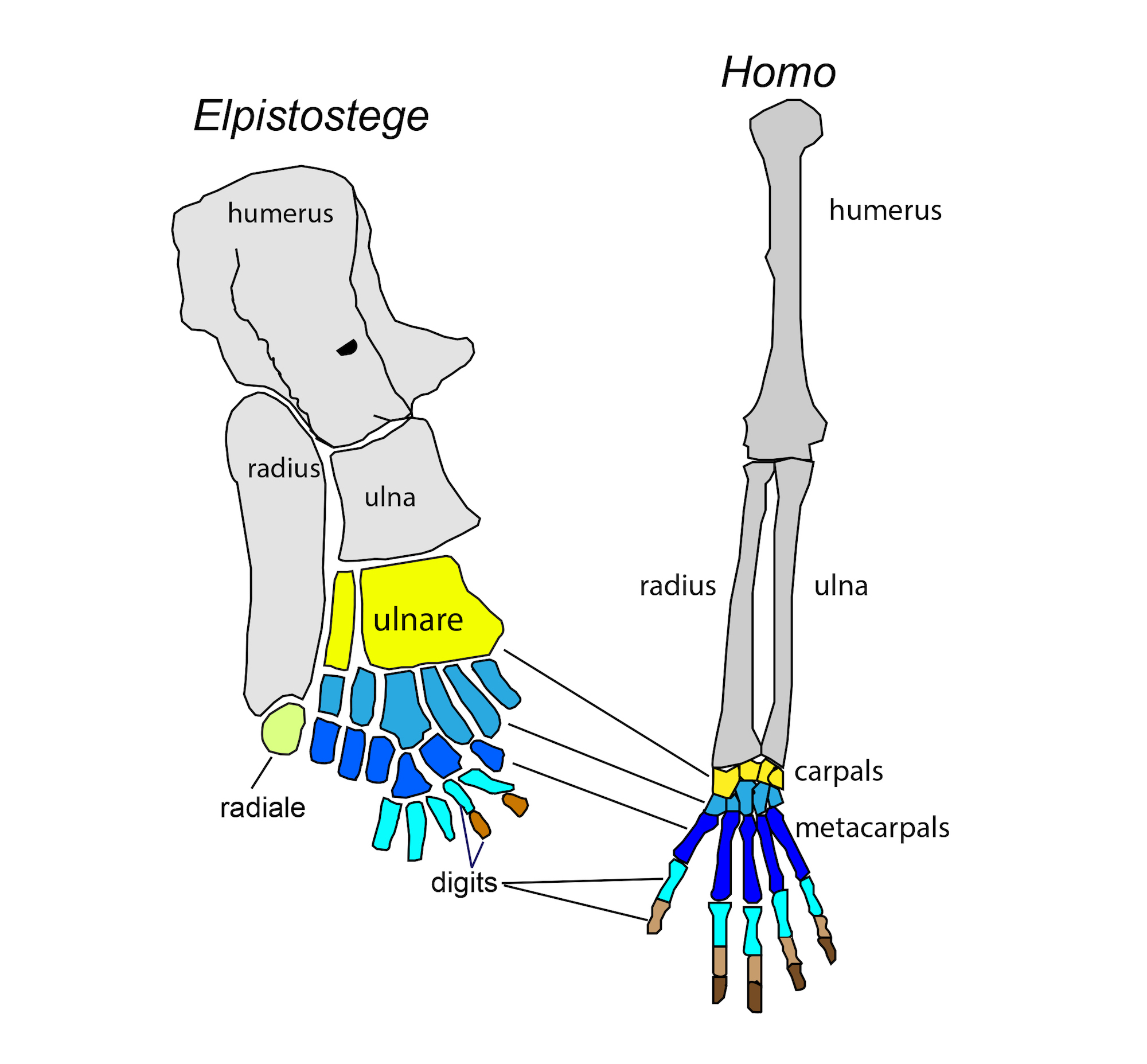

The fish's front fins, known as pectoral fins, immediately caught the researchers' attention. These fins had precursors of vertebrate fingers and arms, including the humerus (arm), radius and ulna (forearm), rows of carpus (wrist), and phalanges organized in digits (fingers), the researchers said. It's these last, distal bones that the researchers described in the new study, published online Wednesday (March 18) in the journal Nature.

Related: In images: The extraordinary evolution of 'blind' cavefish

"This is the first time that we have unequivocally discovered fingers locked in a fin with fin-rays in any known fish," study senior author John Long, professor in palaeontology at Flinders University, said in a statement. "The articulating digits in the fin are like the finger bones found in the hands of most animals."

Small rows of bones in the pectoral fin, which the researchers identified as digits, "show that the basic plan for the vertebrate hand (including our own hand!) must have originated within the fins of advanced, lobe-finned fishes back in the start of the Late Devonian, more than 380,000,000 years ago," Cloutier said.

However, this fish likely didn't walk on its fins. There are too many small bones there, meaning that the fish had a lot of flexibility in the "finger" region, but these fingers weren't optimal for bearing weight on land. "Most likely, Elpistostege was swimming, but it could have stood on its pectoral fins on the bottom of shallow estuarine and fluvial water," Cloutier said.

The fish's upper arm bone, or humerus, also shows features that are shared with early amphibians. However, "Elpistostege is not necessarily our ancestor, but it is [the] closest we can get to a true 'transitional fossil,' an intermediate between fishes and tetrapods," Long said.

Cloutier noted that two of the fish's fingers have two phalanges each and three have one phalange each, unlike humans, who have two or three phalanges per finger. However, not every vertebrate has five fingers, like this fish and humans.

"Early tetrapods had between six and eight fingers," Cloutier said.

After E. watsoni lived, fin rays and scales were lost in the pectoral appendages as tetrapods evolved further and eventually made it to land. Still, all tetrapods share the same basic pattern of digits found in E. watsoni, Cloutier said.

"This discovery and research provide a better understanding of one of the most significant events in the evolution of vertebrates: the origin of tetrapods [and] the transition between aquatic fishes and terrestrial tetrapods," Cloutier said.

- Images: Stunning fish X-rays

- In photos: 'Faceless' fish rediscovered after more than a century

- Photos of the largest fish on Earth

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.