Ancient 'Curse of the Dancer' Deciphered, Revealing Backstabbing Rivals

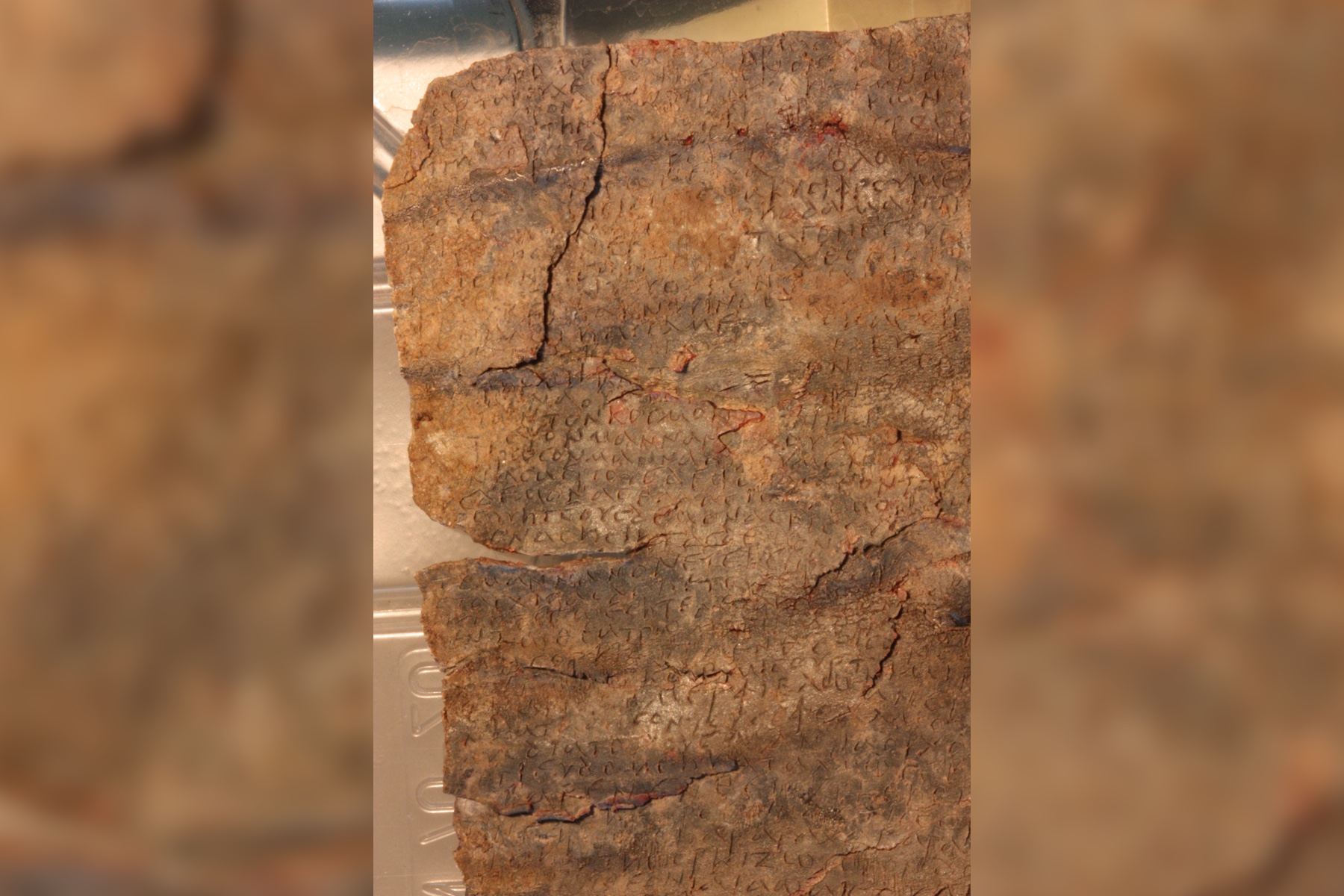

A Greek engraving on a 1,500-year-old lead tablet discovered in the ruins of an ancient theater in Israel has finally been deciphered, revealing a curse that may rival the modern-day backstabbing between athletic opponents.

The curse calls upon numerous demons to inflict harm on a dancer named Manna, who likely performed at the famous Caesarea Maritima theater in Israel, which was built by Herod the Great.

The fact that the tablet was found in the ruins of such a prestigious theater suggests that Manna "must have been a famous artist and therefore the prize would have been considerable, not to mention the fame and reputation that were at stake," for the winner of a dance competition, wrote Attilio Mastrocinque, a professor of Roman history at the University of Verona, detailing his translation of the Greek curse in an article published in the book "Studies in Honour of Roger S.O. Tomlin" (Libros Pórtico, 2019)

Related: Cracking Codes: 5 Ancient Languages Yet to Be Deciphered

And the person cursing Manna wasn't messing around: "Tie the feet together, hinder the dance of Manna," the curse tablet, inscribed in Greek, reads, according to Mastrocinque's translation. "Bind down the eyes, the hands, the feet, which should be slack for Manna when he will dance in the theatre…"

To do this, the curse asks for the assistance of several gods including Thoth, an ancient Egyptian god of magic and wisdom. It also calls upon the "demons of the sky, demons of the air, demons of the earth, underworld demons, demons of the sea, of the rivers, demons of the springs…" to hurt Manna.

"Twist, darken, bind down, bind down together the eyes…" of Manna the inscription says. "He should move slowly and lose his equilibrium" and "he should be bent and unseemly…"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The curse tablet was discovered by an Italian archaeological team sometime between 1949 and 1954, but the inscription was difficult to make out. It was only recently that Mastrocinque deciphered it, using a method called Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI). With RTI, a computer program creates numerous photographs of an artifact — taken from different lighting angles — to create an enhanced image.

The curse tablet dates to the sixth century, a time when the Byzantine Empire controlled the city.

Taking that period into account, it's possible that Manna and the curse-writer were from warring factions. In the Byzantine Empire, people competing in dance or other competitions were sometimes part of rival factions — such as the "blue" and "green" factions — and the competition between these factions could be intense, sometimes even resulting in public riots, Mastrocinque wrote.

Whatever the reason, the curse tablet is lengthy, containing 110 lines. While the Byzantine Empire used Christianity as its official religion, and Christianity didn't worship Thoth and other "pagan" gods often named in curse tablets, this didn't stop the use of curse tablets, Mastrocinque wrote, noting that if anything these tablets became longer and more detailed.

"This [curse tablet] along with many others issued in the late imperial period and in the early Middle Ages, confirms that the Christianization of the Roman Empire did not stop the maleficent magical arts… on the contrary, these increasingly spread and became more sophisticated," Mastrocinque wrote.

The tablet was given to the team by the Israeli government and it is now in the Archaeological Museum of Milan.

- 30 of the World's Most Valuable Treasures That Are Still Missing

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

- In Photos: Biblical 'Church of the Apostles' Discovered

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus