10 amazing health stories you may have missed in 2021

Here's the medical news you may have missed this year.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For a second year, the COVID-19 pandemic has dominated health news headlines, and for good reason. But amid all the talk of viral variants and vaccine boosters, you may have missed some of this year's most amazing medical cases and breakthroughs. In 2021, scientists made great strides in the world of organ transplants, cancer treatment trials and gut microbiome research, and doctors shared some amazing treatment success stories.

Here are 10 cool medical stories you may have missed this year.

Baby born at 21 weeks survives, against all odds

Curtis Means and his twin, C'Asya, were born only 21 weeks and 1 day into their gestation, meaning they were about 19 weeks premature. C'Asya did not respond to treatment and died shortly after birth, but Curtis' vitals steadily began to improve. Even so, doctors estimated that he had only a 1% chance of survival. Over the following months, he received constant care to maintain his breathing and body temperature, and to take in adequate nutrition. He was able to come off his ventilator at 3 months old, and he was discharged from the hospital at 9 months. After six months at home, Curtis and his family received a Guinness World Record certificate acknowledging Curtis as the most premature baby in the world to survive.

Read more: Baby born at 21 weeks survives, breaks world record

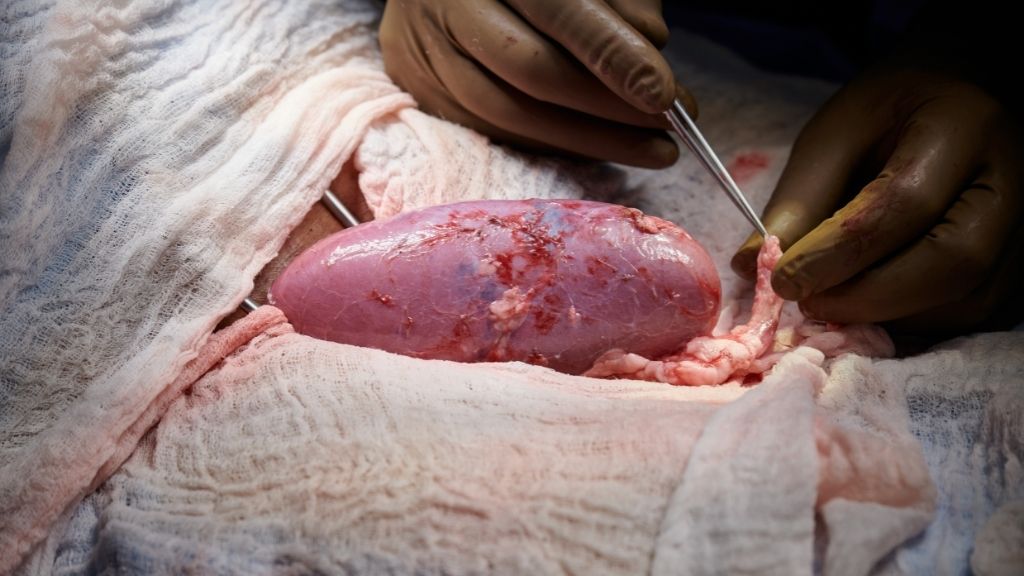

Working pig kidney is successfully hooked up to a human

With human organs in short supply for transplant surgeries, scientists have long been working to make animal-to-human transplants safe, feasible and widely available. This year, in a watershed experiment, doctors connected a pig kidney to a human and watched as it effectively filtered waste from the body and produced urine. The experiment was conducted in a brain-dead patient who was a registered organ donor and whose family granted permission for the procedure. The team used a kidney from a genetically modified pig that lacked the gene for alpha-gal, a type of sugar that can trigger an intense immune reaction in humans. The successful experiment could signal a big step forward for animal-to-human transplants, but many questions remain.

Read more: Pig kidney successfully hooked up to human patient in watershed experiment

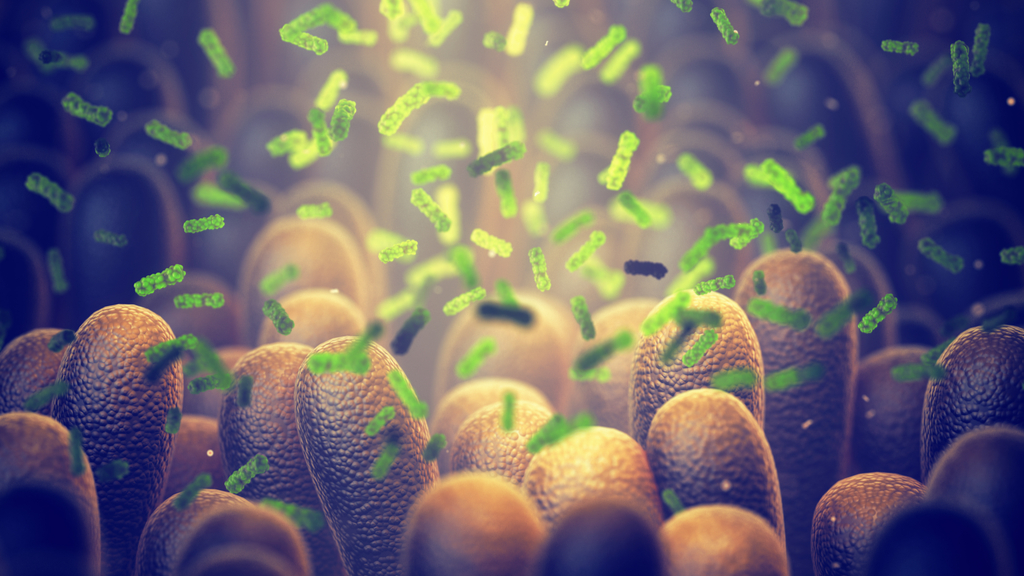

Poop transplants boosted skin cancer patients' treatment

Immunotherapies theoretically rally the immune system against cancer cells, but they don't work for all cancer patients. Only about 40% of patients with advanced melanoma, for instance, reap long-term benefits from immunotherapy drugs. But a small study published in February in the journal Science hints that tweaking cancer patients' gut bacteria can help boost the drugs' effectiveness.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the study, scientists collected stool from melanoma patients who responded well to immunotherapy and then transplanted the patients' feces — which was chock-full of microbes — into the guts of 15 patients who had never responded to the drugs. After the transplant, six of the 15 patients responded to immunotherapy for the first time, showing either tumor reduction or disease stabilization that lasted more than a year. Looking forward, the scientists plan to investigate exactly why the poop transplant helped these six patients and why the other nine patients didn't seem to benefit.

Read more: Cancer patients weren't responding to therapy. Then they got a poop transplant.

Discovery reveals potential weapon against bacterial superbugs

A study conducted in lab dishes and mice hints at a new way to take down drug-resistant bacteria. This new weapon could make existing antibiotics more effective, thus reducing the need to formulate brand-new antibiotic medications. In the study, published in June in the journal Science, scientists ran experiments with Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, two bacteria that show pervasive resistance to multiple drugs and rank among the leading causes of hospital-acquired infections. These so-called superbugs use a specific enzyme to shield themselves from harm by antibiotics, so the team searched for molecules that could block the enzyme and leave the bugs defenseless. The molecules the scientists identified made antibiotics two- to 15-fold more potent against the microbes, depending on the antibiotic being used and the bacterial strain being targeted. Now, they'll have to see if the same strategy can work in humans.

Read more: New discovery could help take down drug-resistant bacteria

A second person is "naturally" cured of HIV

A woman now known as the Esperanza Patient was diagnosed with HIV, the virus that can cause AIDS, in 2013. But as of this year, doctors can find no trace of the virus in her body. The woman received neither a bone marrow transplant nor any drug intervention; her immune system has apparently eliminated HIV from her system on its own. This had happened once before, in a California woman named Loreen Willenberg. And although the two women are anomalies, their cases give scientists hope of finding a cure for HIV/AIDS.

Read more: Patient's immune system 'naturally' cures HIV in the second case of its kind

Cancer vaccine shows promise in small trial

An experimental "cancer vaccine" works by training immune cells to better recognize and attack cancer cells in the body, without harming healthy cells. In a small trial of eight patients with advanced melanoma, the vaccine helped prevent the patients' tumors from growing for years after vaccination. By the end of the four-year follow-up period, all eight patients were alive and six out of eight showed no signs of active disease. Two had experienced cancer recurrence and received additional treatments called "checkpoint blockades," which essentially rip the brakes off of immune cells known as T cells. In combination with the T cell-targeting cancer vaccine, these checkpoint blockades were highly effective. This hints that such vaccines could serve as a very important therapy, to be used in tandem with other cancer treatments, but more and larger trials are still needed to know for sure.

Read more: Cancer vaccine helped keep melanoma under control for years in small study

Dietary supplement restores gut bugs, helps malnourished kids grow

A new dietary supplement helped malnourished children put on weight and gain height at a faster rate than children who were given a standard "ready-to-use supplementary food." What made the difference? The new supplement helped to restore the kids' gut bacteria so they more closely resembled the gut bacteria of healthy children.

Malnourishment leaves kids' gut microbes "stunted," as the microbes don't have adequate fuel to grow and multiply. Through exhaustive animal studies and a small pilot trial with human children, a team of scientists came up with a formula to both deliver kids the calories they need and help restore their gut bacteria. In a larger trial, published in April in The New England Journal of Medicine, they found that the supplement not only helped kids grow faster but also increased the concentrations of key proteins in their blood, including those involved in bone growth and nerve and brain development.

Read more: Tweaking the gut bacteria of malnourished kids could help them grow

Experimental HIV vaccine successfully stimulates rare immune cells

The first in-human trials of a new HIV vaccine stirred up excitement about the experimental shot, as it showed 97% success at stimulating a rare set of immune cells that play a key role in fighting the virus.

The human immunodeficiency virus poses a huge challenge for vaccine developers because it mutates so quickly, but in this case, the researchers targeted the pathogen using a unique approach: They designed their vaccine to target a specific subset of B cells, a kind of immune cell that produces "broadly neutralizing antibodies," proteins that can latch onto a key protein on HIV and stop the virus from infecting cells. In a trial of 48 people, the vaccine was safe and induced neutralizing antibody production in 97% of the participants. Although this hints that the vaccine may work well, the trial didn't directly test whether the vaccine prevented HIV infection; that will be the next step in development.

Read more: HIV vaccine stimulates 'rare immune cells' in early human trials

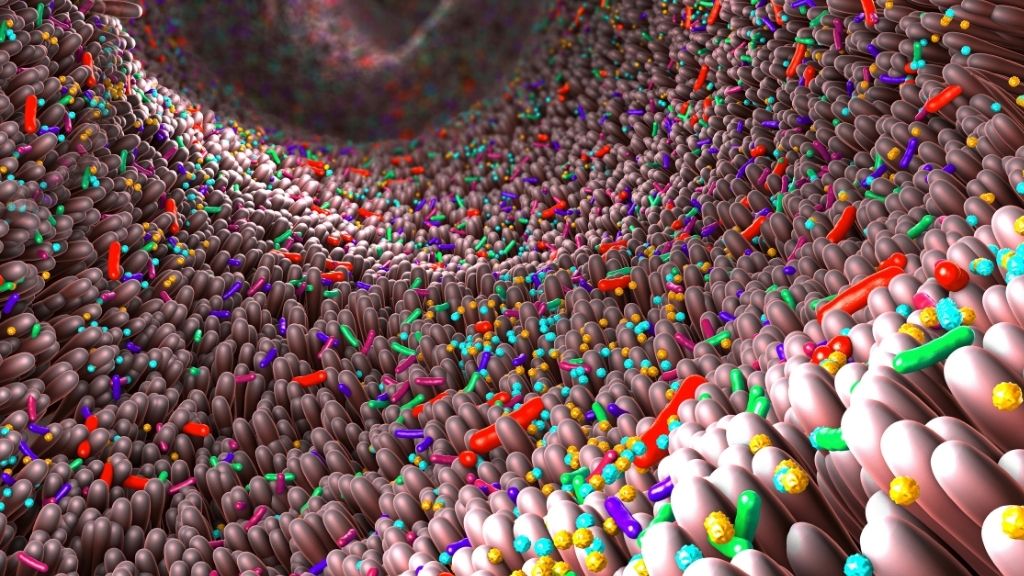

Centenarians' gut bacteria may hint at how they survive to 100

People who live to age 100 and beyond may partially have their gut bacteria to thank, according to a study published in July in the journal Nature. In the study, researchers examined the communities of gut microbes, or microbiota, living in 160 centenarians, who were, on average, 107 years old. The researchers compared the centenarians' gut microbiota to those of 112 people ages 85 to 89, and 47 people ages 21 to 55. The centenarians showed a distinct gut microbe "signature," meaning specific microbes appeared in higher or lower abundance than in the younger groups. In addition, they had significantly higher levels of so-called secondary bile acids, a fluid produced by the liver and released into the intestine. In particular, they produced high concentrations of the secondary bile acid isoalloLCA, which the researchers found to have potent antimicrobial properties that may inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria in the gut.

More research is needed to know if and how the centenarians' gut bugs help them survive to such advanced ages and whether this knowledge could be used to boost other people's longevity.

Read more: People who live to 100 have unique gut bacteria signatures

HPV vaccine cuts cervical cancer rates more than 85% in UK women

A recent study found that the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine has reduced the number of cervical cancer cases by 87% among women in the U.K. Using cancer registry data gathered between 2006 and 2019, researchers compared the cervical cancer rates among women who were vaccinated with the HPV vaccine Cervarix when they were young, between the ages of 12 and 13, with the cervical cancer rates of women who received the vaccine slightly later and with the rates of those who did not receive the vaccine at all.

The researchers found that the vaccine was most effective when given to the youngest cohort; women who had been vaccinated with Cervarix between the ages of 12 and 13 had 87% fewer cases of cervical cancer compared with those who weren't vaccinated. There was a 62% reduction in cases among women who had been vaccinated between the ages of 14 and 16, and a 34% reduction in cases in women vaccinated between 16 and 18, compared to the unvaccinated population.

Read more: HPV vaccine slashes cervical cancer rates by 87% among women in the UK

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus