New Approach Disarms Deadly Bacteria

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

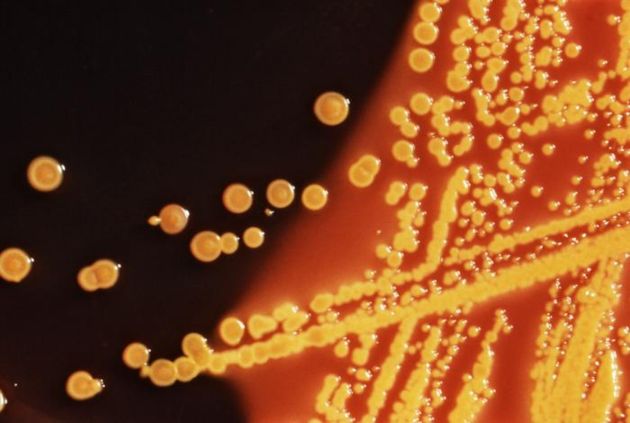

A warmer, gentler approach to controlling bacteria may be the answer for the emerging menace of drug-resistant diseases.

For more than 50 years antibiotics, such as penicillin, have been the ammunition in war against a rogues gallery of scourges from tonsillitis to typhoid fever. Recently, however, antibiotics have begun to lose their mojo.

So many strains of bacteria now shrug off garden-variety antibiotics that scientists at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration have tagged drug resistance as a growing threat to human and animal health. Just some of the diseases that are increasingly hard to treat are tuberculosis, gonorrhea, malaria, and the ear infections that plague little kids.

Health experts warn that if bacteria keep toughening up, some deadly diseases that have been treatable for the last five-plus decades again will have no cure.

Disarming approach

A better battle plan may be to make nice. Instead of killing off disease-causing bacteria, just disarm them, said bacteriologist Marcin Filutowicz. The problem with traditional antibiotics is that they use the neutron bomb approach: they indiscriminately kill off bacteria, and for potent drugs and high doses can bump off virtually every bacterium in a patient's body.

That causes a couple of problems, Filutowicz said. One is that the bacteria the body needs, such as to aid digestion, can be collateral casualties. The other is that clear-cutting the body's bacteria leaves fertile ground in which new bacteria can grow. And the bacteria that move into this available real estate are usually the ones that were brawny enough to survive the antibacterial barrage.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When you start repopulating your skin, your GI track, your nostrils, all of the non-sterile parts of your body, then opportunistic pathogens have as equal a chance of repopulating your body as the good bacteria," Filutowicz explained.

The process of killing off vulnerable bacteria while providing territory for tough bacteria to occupy leads to drug-resistant diseases, Filutowicz said. But if harmful bacteria--for example, the Neisseria meningitidis that causes spinal meningitis--could be left in place, but modified so that it couldn't cause the disease, drug-resistant strains wouldn't have space in which to expand.

Toothless

Filutowicz and his colleagues at the University of Wisconsin at Madison have begun exploit a weakness in the structure of bacteria.

Some small organisms, including bacteria, store their DNA two ways, on the chromosome and on what are called "plamids," little chunks of DNA that are not vital to keeping a bacteria alive. The genes that let some bacteria causes disease (their "virulence genes) and the genes that protect bacteria from antibiotics (their "antibiotic resistance genes") ride plasmids.

The weapon of choice for attacking these troublesome plasmids is "displacins," which are bits of DNA from other kinds of bacteria, he said. These displacins can displace plasmids from bacteria cells, leaving the bacteria toothless, but alive.

"The charm and the power of displacin technology is that you don't kill the culprit, but you disarm it," Filutowicz said. "And because you disarm bacteria of their virulence and antibiotic resistance genes, you don't produce a void in their environment. This is critical, that you don't produce the emptiness in the environment that then can be competed for by pathogens and non-pathogens to occupy this void."

The research group has a library of millions of DNA fragments from bacteria, some from the 3 percent or so of bacteria that can be cultured in laboratories, but most extracted from the 97 percent of bacteria that grow only in nature. In fact, their DNA library has been culled from bacteria that live in soil. The scientists' compassionately conservative strategy is to splice displacins that disarm specific bacteria onto E. coli bacteria (but not the news-making toxic kind).

These E. coli will carry the bad-bacteria-busting displacins into the battlefield that is a patient's body without, Filutowicz hopes, losing the drug-resistance war.

Related News

Deadly Bugs Survive for Weeks in Hospitals

Possible First Major New Class of Antibiotics in Decades

War on Bacteria is Wrongheaded

More to Explore

The Sexiest Stories of 2006

The Weirdest Science Stories of 2006

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus