US Embassy Staff in Cuba Show Unusual Brain Changes After Alleged 'Sonic Attacks'

More than two years after several dozen U.S. embassy workers in Cuba reported experiencing bizarre sensory symptoms, including loud noises and unusual vibrations, exactly what happened to them remains a mystery.

Now, a new study adds to the intrigue.

The study, which used advanced brain-imaging technologies, revealed distinct differences in the brains of embassy workers who were potentially exposed to the bizarre phenomena, compared with healthy people who were not exposed.

In particular, the researchers found differences in a brain area known as the cerebellum, which is responsible for coordination of movements, such as those involved in walking and balance, according to the study, published today (July 23) in the journal JAMA. [27 Oddest Medical Case Reports]

This finding is notable given that a number of the embassy workers show abnormalities in balance and coordination of eye movements, said study co-author Dr. Randel Swanson, an assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine. However, the researchers acknowledge that they can’t say exactly what their findings mean or what caused the brain differences. In other words, the study doesn't bring us any closer to understanding the cause of the alleged phenomena.

Still, it appears that "something happened to at least a subset of [these] patients," Swanson told Live Science.

It's possible that the brain differences seen on the images may underlie some of the symptoms documented in the embassy workers, he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mysterious "attack"

In late 2016, some U.S. embassy workers serving in Havana reported hearing sudden, loud noises or feeling vibrations or movement in the air around them, Live Science previously reported. These experiences were followed by a variety of neurological symptoms, including dizziness, balance problems and difficulty with concentration and memory.

Officials initially suspected some type of "sonic attack" was behind the cases, but this was never proven.

In 2018, the same group of researchers at UPenn published a study that documented neurological symptoms of 21 of the Havana U.S. embassy workers. That study found that many of those individuals had symptoms similar to those seen in people with concussions or mild traumatic brain injury, although in the Havana cases, there was no evidence of blunt head trauma, the authors said. At that time, the researchers also noted that it was unclear how exposure to sounds — even a sonic weapon — could have caused such symptoms. [Mind-Controlled Cats?! 6 Incredible Spy Technologies That Are Real]

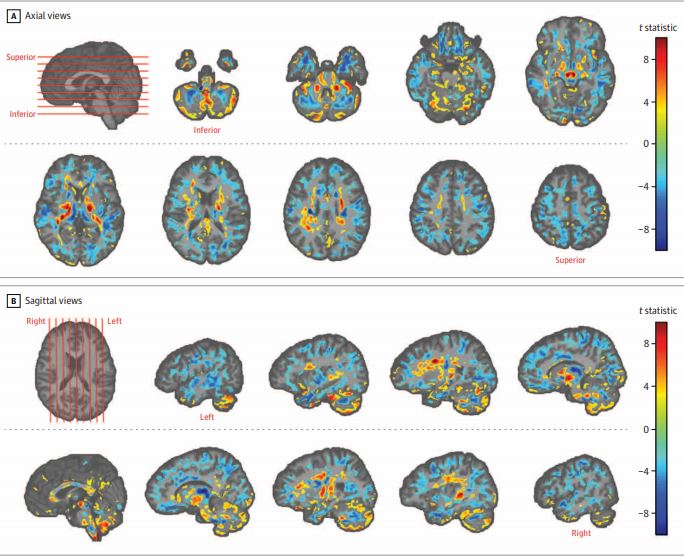

In the new study, the researchers analyzed brain images of 40 potentially exposed U.S. embassy workers, and 48 healthy people who were not exposed to the alleged phenomena. All of the participants had their brains scanned with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Among the embassy workers, the brain scans were performed, on average, about six months after the reported exposure.

The brain images showed that, compared with healthy people, the U.S. embassy workers had lower volumes of white matter — long nerve fibers that allow areas of the brain to communicate, the study found.

In addition, compared with healthy people, U.S. embassy workers showed differences in brain tissue volume and tissue integrity in their cerebellum.

The particular pattern of brain differences seen in the study is unlike that of any other brain disease or condition seen in previously published research, the authors said.

"These findings may represent something not seen before," study co-author Dr. Douglas Smith, a professor of teaching and research in neurosurgery at UPenn, said in a statement.

Brain changes?

Martha Shenton, a professor of psychiatry and radiology at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, who wasn't involved in the study, said that the new work used "some of the best ways of looking at the brain using neuroimaging." But, like the the authors of the new study, Shenton thought the clinical meaning of the findings is unclear, and will require further study.

The researchers noted that, because the brain scans were conducted largely after the patients had undergone rehabilitation treatment, it's possible that the brain changes seen in the study were due to the process of rehabilitation for brain recovery, rather than some type of injury itself.

"We can't definitively say that these brain differences are related to whatever happened to these individuals in Havana," said Evan Gordon, an investigator at the Center of Excellence for Research on Returning War Veterans in Waco, Texas, who wasn't involved with the study.

It's also possible that the findings might be explained by "reverse causality," Gordon said. In other words, the embassy staff may have had underlying brain differences that made them more vulnerable to what happened to them, although Gordon said this possibility was unlikely.

"On balance I would say that the more likely explanation is that the event these individuals suffered did indeed affect their brains," Gordon told Live Scinece.

Gordon also noted that some of the effects seen in the patients' brain tissue were opposite to what is seen normally in TBI patients.

This "suggests that their brains were affected in some fundamentally different way than brains that have suffered a TBI," Gordon said. "It’s possible — though by no means certain — that whatever caused these changes is a genuinely new effect."

Editor's note: This article was updated on July 23 at 3:00 pm ET to include quotes from Martha Shenton and Evan Gordon.

- Flying Saucers to Mind Control: 22 Declassified Military & CIA Secrets

- The 7 Biggest Mysteries of the Human Body

- Mind-Controlled Cats?! 6 Incredible Spy Technologies That Are Real

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.