Ruling Out 'Sonic Attack,' Docs Still Mystified by Brain Damage in US Staff in Cuba

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Last year — in a scenario that could double as the plot of a sci-fi flick — U.S. embassy workers in Cuba reported unexplained cognitive problems after hearing strange noises, with some initially saying that a "sonic weapon" was at play.

Now, the mystery deepens, as a new report reveals that while the embassy workers do indeed have symptoms of mild traumatic brain injury, the cause of the injury remains unknown.

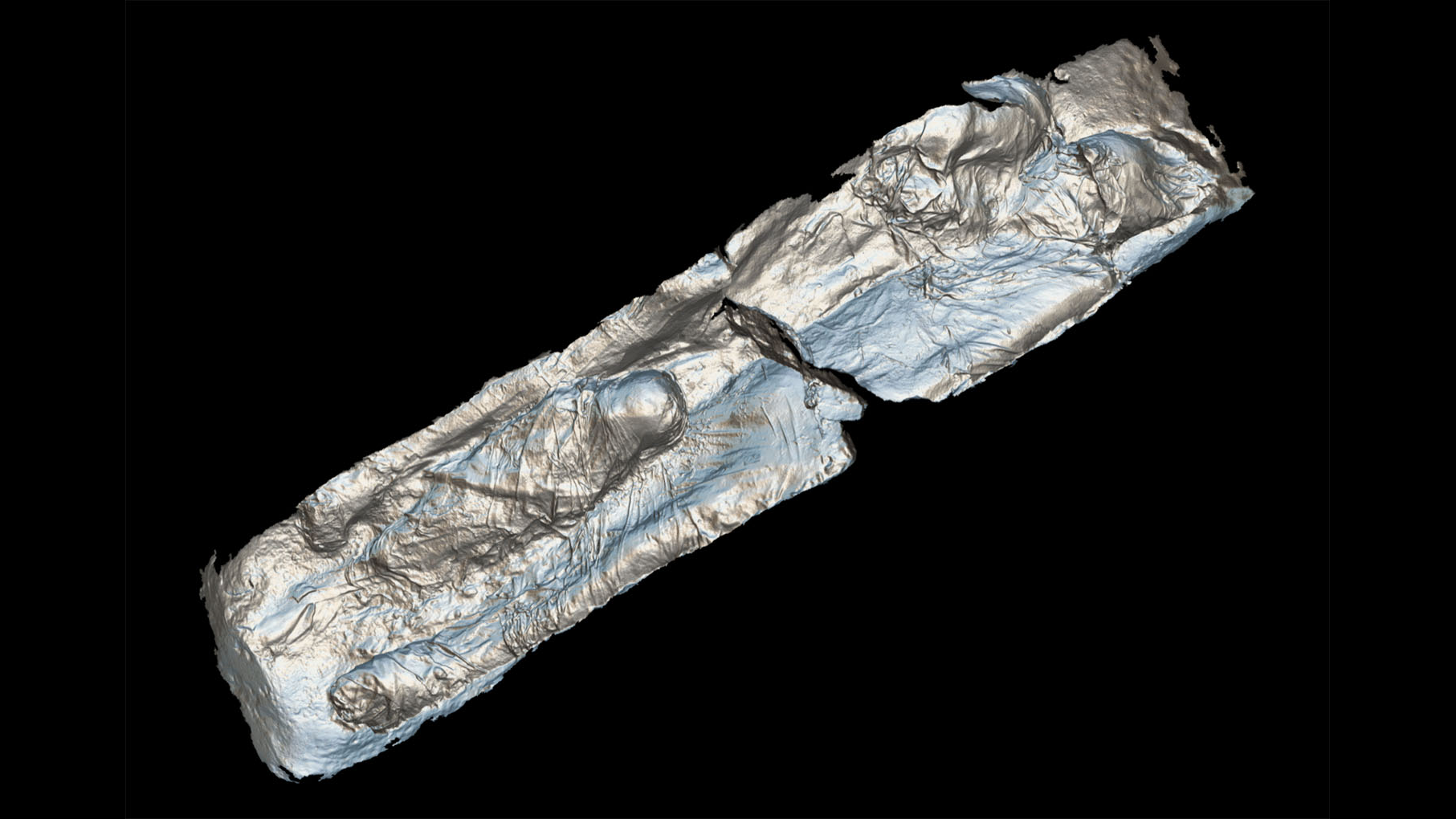

In the report, published Feb. 15 in the journal JAMA, a team of doctors at the University of Pennsylvania examined the 21 embassy workers, documenting symptoms similar to those of a concussion, including cognitive impairment, balance issues, hearing problems, sleep issues and headaches. But their findings suggest that none of the proposed causes for these mass brain symptoms (including sonic weapons) really make sense. [The 7 Biggest Mysteries of the Human Body]

As Live Science previously reported, the workers heard loud, strange noises and felt movement in the air around them — even as others in the room sensed nothing amiss. The noises would stop when an afflicted worker moved even a few feet, according to The Washington Post. But afterward, serious concussion symptoms would emerge.

When the cases were originally reported in the press last year, it was widely suggested that the symptoms might be the result of some sort of "sonic weapon." However, the researchers said that this is unlikely: "Sound in the audible range (20 Hz to 20,000 Hz) is not known to cause persistent injury to the central nervous system," they wrote.

The cases also don't fit the typical patterns of a mass delusion they wrote. Mass delusions typically involve benign symptoms that resolve quickly and appear mostly in older patients. These symptoms were not benign, the patients were broadly distributed in age, and the symptoms did not quickly disappear despite the patients' demonstrated "high levels of effort and motivation" to treat them.

And although the researchers couldn't rule out viruses or chemical agents as the cause, no typical symptoms of viral infections, such as fevers, accompanied the symptoms. And it's "unlikely," they wrote, that a chemical agent could damage neurological systems without involving other organs — or cause symptoms within 24 hours of arrival in Havana, as was the case for some patients.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers did clarify that the patients' symptoms don't exactly match typical concussions, as the most unusual symptom that they documented was inner-ear damage — something not typically associated with concussions. But an answer to what exactly happened to the affected workers doesn't seem much closer.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus