'Ghost Base' Perched on a Growing Ice Chasm in Antarctica Is Running on Its Own

A remote science station in Antarctica forced to close over the polar winter by a dangerous ice chasm is completely empty of human life — a ghost base of sorts. Even so, its vital science experiments keep on ticking.

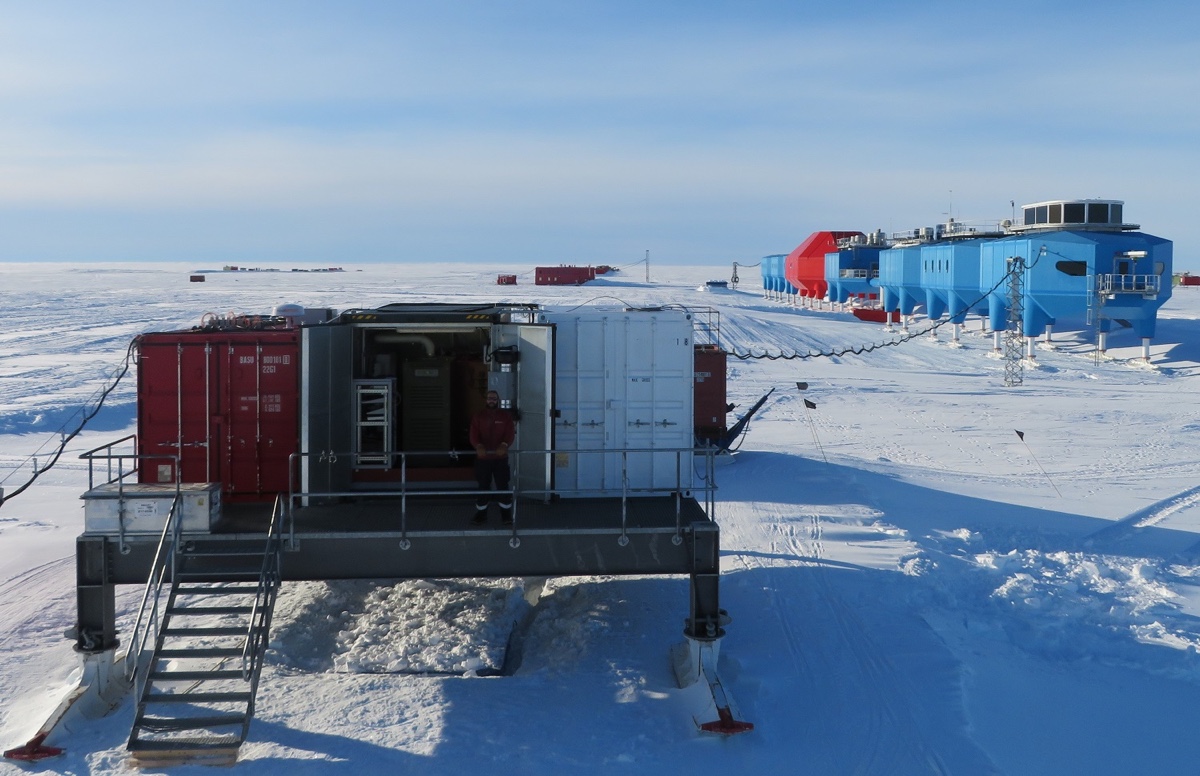

It is the first time that important science experiments at the Halley Research Station on the Brunt Ice Shelf have been operated remotely, thanks to a high-tech electricity generator that will run continuously for nine months in the below-freezing conditions.

The generator and the science experiments that depend on it — including measurements of the ozone hole over Antarctica and global monitoring of lightning activity — passed the middle of the southern polar winter (complete darkness) a few days ago, on June 21. [Antarctica: The Ice-Covered Bottom of the World (Photos)]

That's already more than four months of continuous operation, including times when the temperature was more than minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 40 degrees Celsius), and the polar winds were blowing snow at up to 50 mph (80 km/h) , said Thomas Barningham, the project leader for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

"That is a significant milestone for us, so we are very pleased with the progress of the new power system," Barningham told Live Science.

The Halley scientific research station has been operated by the BAS on the Brunt Ice Shelf since 1956, and rebuilt in the same location several times.

In 1985, scientists at the fourth Halley station built on the ice shelf reported the detection of the Antarctic ozone hole, which has been linked to the accumulation of chlorine-based chemicals in the upper atmosphere.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

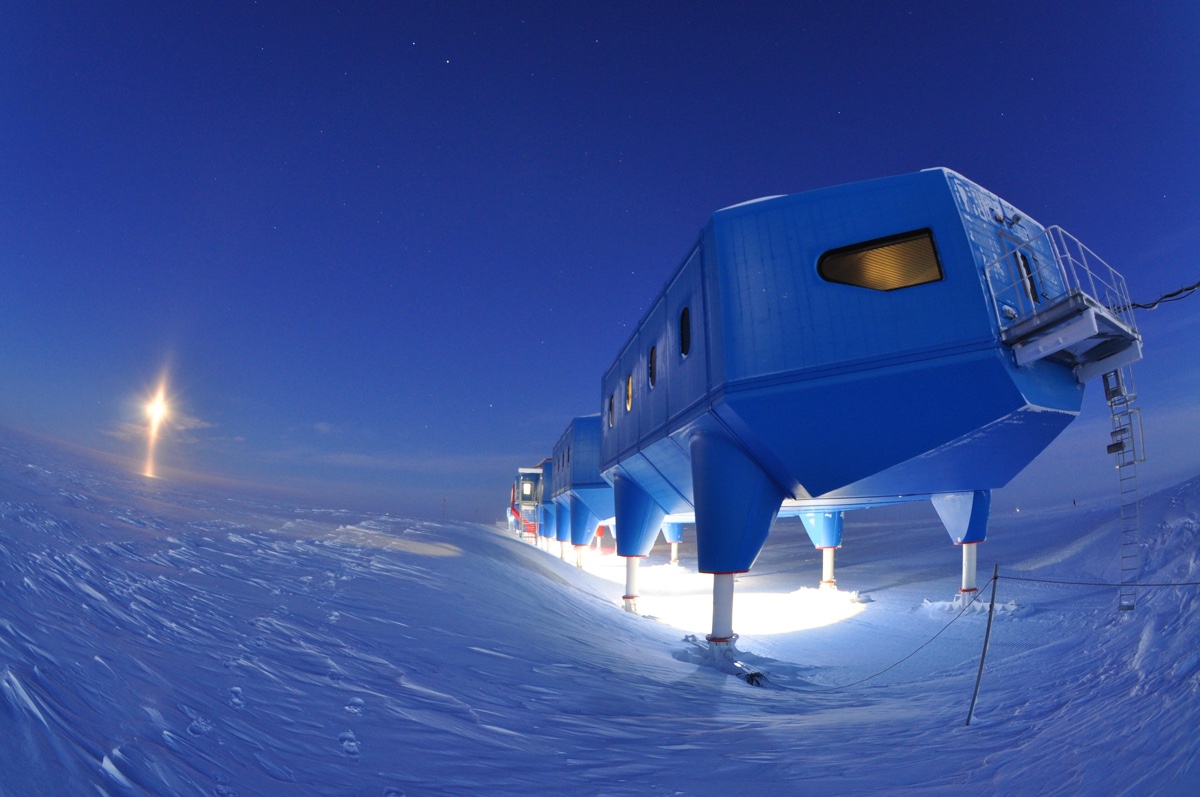

But in 2017, the mobile buildings of the sixth Halley station were forced to move to a new location, 12 miles (20 km) away, to avoid the danger of being cut adrift by a growing chasm in the ice shelf.

Polar science by remote

A crew of 14 scientists and technicians previously kept the station's science experiments going over the polar winter. But Halley has been closed over the winter since 2017, because the BAS decided it would be unable to rescue staff by aircraft or ship if the ice shelf split away.

As a result, instruments like the Dobson photospectrometer, which measures the ozone layer in the atmosphere, were switched off for the winters of 2017 and 2018, because the existing diesel generators couldn't run for more than a few weeks without people. [Extreme Living: Scientists at the End of the Earth]

But now the essential experiments are kept running and connected to satellite internet by a gas micro-turbine — effectively a small jet engine in a box, connected to an electricity generator.

Barningham said the generator was switched on in February and was expected to run until November, supplying up to 13 kW of electricity to the science experiments at the research station, and using around 10,500 gallons (40,000 liters) of kerosene fuel in that time.

Both the micro-turbine generator and the science experiments are being monitored around the clock by satellite internet from the BAS headquarters at Cambridge in the U.K., he said.

If the generator should switch off for any reason, Barningham is even able to fire it back up remotely. "I can send a command within 24 hours to issue a restart, and — God forbid if we have got to that point — fingers crossed, it would just kick back in again and off we go."

Barningham will be among the first staff to return to the Halley research station when it opens for a new summer season in November, when he expects to find the micro-turbine generator still operating smoothly.

"This is the first time that we've done this, it is a prototype, so there could always be things that are thrown up that we haven't quite expected," he said. But "it is going well at the moment, and we are very pleased."

- Antarctica Photos: Meltwater Lake Hidden Beneath the Ice

- Photos: Diving Beneath Antarctica's Ross Ice Shelf

- In Photos: Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf Through Time

Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus