Survival of the Grossest: 8 Disgusting Animal Behaviors

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Nasty habits

From eating poo to expelling snot-bombs, some animal habits seem downright revolting. But though they might be repulsive to humans, these behaviors are critical for animals' survival. Here are just a few of the more unsavory adaptations in the animal kingdom.

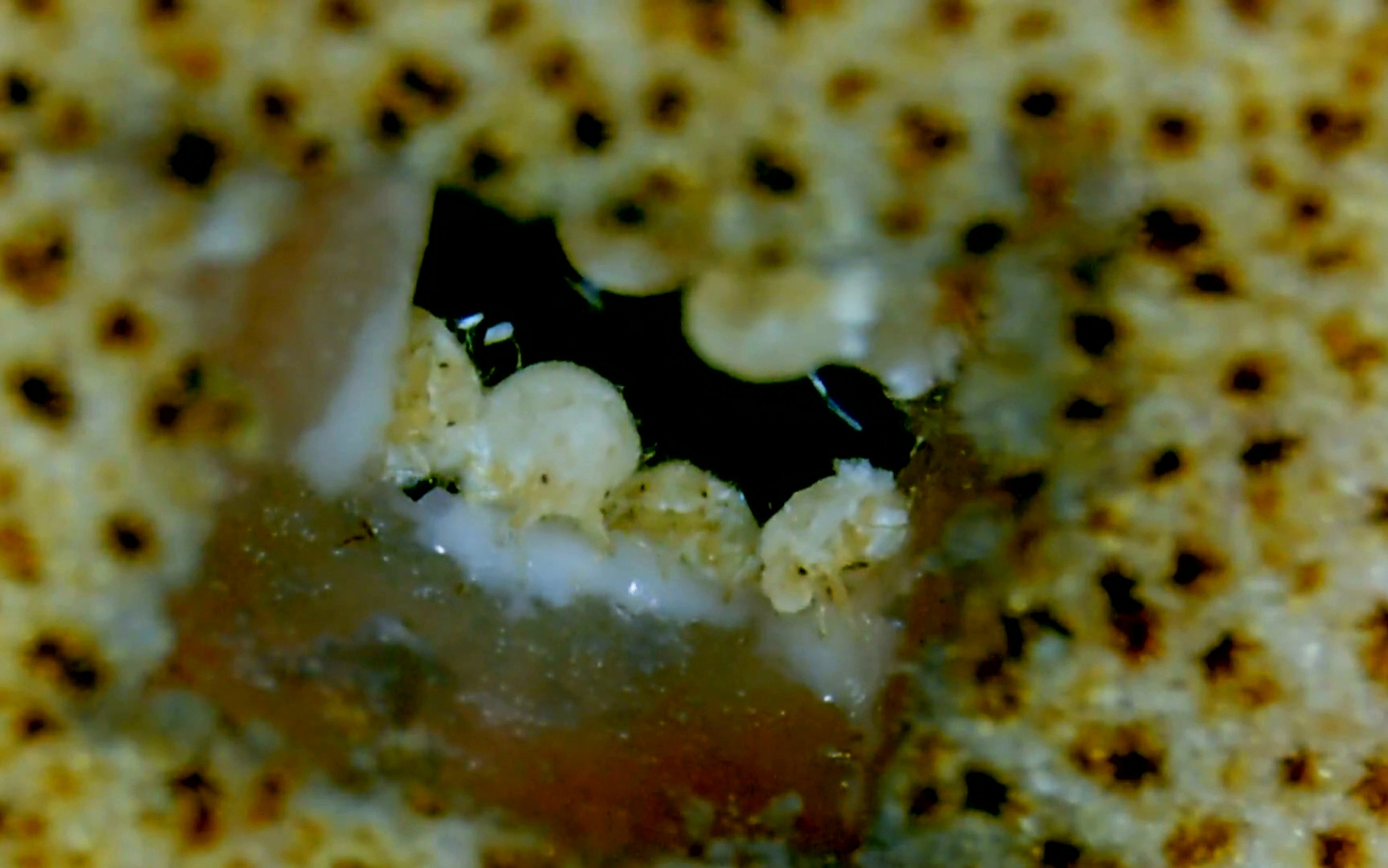

Popped like a pimple

Aphids that live in plant-grown nests called galls have a defense strategy that will delight fans of pimple-popping videos: They expel squiggly streams of sticky white goo, using their legs to mix it and then patching cracks and holes in their homes.

Soldier nymphs secrete so much of this goop that they deflate to a fraction of their former size. Even after "erupting," they continue to mix and spread the goo, and some of them end up permanently plastered into the seal as it closes, according to a study published April 30 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Article continues belowHungry for poo

Coprophagia, or poop-eating, is common in the animal kingdom, practiced by dogs, rabbits, many species of rodents and even some non-human primates such as gorillas and orangutans. This behavior provides animals with nutrients that they couldn't otherwise access from their diets, and is an important part of gut health.

Some animal babies will consume their mother's poop, to help them transition from an all-milk diet to one that includes solid food. Elephant and hippo calves eat maternal poo, and an autopsy of a 42,000-year-old mammoth calf named Lyuba found evidence in her stomach that mammoth poo was on the menu for her last meal.

Hard to stomach

When toads swallow bombardier beetles, the insects set off a "bomb," mixing chemicals to create a hot and explosive spray inside the toad's gut. But toads can't vomit as humans and other animals do, as some unlucky amphibians demonstrated in a study documenting their responses to a toxic beetle meal.

To get rid of the beetle, the toads everted their stomachs through their mouths; the stomach popped up and flipped inside-out like a pocket, dumping the beetle on the ground. After the offending insect was removed, the toads sucked their stomachs back inside where they belonged

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Roadside slime

Hagfish that are stressed or threatened release a secretion of mucus and protein fibers that mix with water to create goopy slime, a defense that clogs the gills of predators. While hagfish usually confine their sliming to the seafloor, a 2017 road accident in Oregon was complicated by copious amounts of hagfish slime.

When a truck carrying 7,500 pounds (3,400 kilograms) of hagfish overturned on a highway, the spilled hagfish produced so much slime that officials had to close the road in order to clean up the mess, blasting it into nearby ditches with high-pressure hoses.

Tongue-replacer

Many types of parasites affect fish, but the most horrifying of them all is probably Cymothos exigua, also known as the tongue-eating louse. This crustacean is the only known parasite to entirely replace a host's organ — the tongue — with its own parasitic body.

C. exigua enters a fish's body through the gills, then attaches to the base of the tongue with its legs, where it sucks blood from the tongue until it shrivels up and drops off. After that happens, the parasite stays attached to the fish's tongue base, serving as a living replacement for the lost organ.

Out with a bang

An ant species called Colobopsis explodens practices a self-sacrificing defensive move for the good of the colony; workers trigger a chemical reaction in their bodies that produces an explosive gush of goo. While this fluid is toxic to intruders and predators, the explosion also fatally ruptures the ants' bodies.

Researchers found that the suicidal move is only performed by sterile females. They manufacture a yellow secretion in their jaw glands, and then powerfully expel it by clenching a part of their abdomens called the gaster. The goo has "a distinctive spice-like odor," the scientists reported.

Inside-out

Otters have an ingenious (and gory) solution for eating toads that have toxic glands in their skin: the carnivorous mammals peel the skin off the toad, turning it inside out so they can safely devour its flesh and organs.

A photo of an inside-out toad that was recently captured in the United Kingdom during a nature walk revealed the grim evidence of an otter's meal. The toad's skin, still attached at the lower jaw, arched over its back, and its intestines and other digestive organs were visible.

Butt-gouging

Researchers working with seals on an island off the coast of Chile discovered unusual wounds on the pups' rear ends. They quickly discovered that the gouges had an unlikely source: gull beaks.

Many of the seal pups were infected with parasitic hookworms, which emerge in the seals' feces. Apparently the sea birds found hookworms to be so delicious that they were pecking at the baby seals' butts to eat the worms that the seals were pooping out. The birds were so eager to nab the tasty snacks that as they ate, they repeatedly jabbed the young seals' tender bottoms.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus