Toad Eats Beetle, Immediately Regrets It — Watch Retching Aftermath

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Toads might want to be careful what meal they catch with their sticky, pink tongues. It could be a toxic beetle that makes them throw up … and then scurries away to tell the tale, a new study from Japan finds.

Unfortunately, toads have to learn this lesson the hard way. After nabbing these brown and black insects, known as bombardier beetles (Pheropsophus jessoensis), a toad will likely feel an explosion in its gut, indicating that the beetle has just let loose a toxic chemical cocktail, the researchers found.

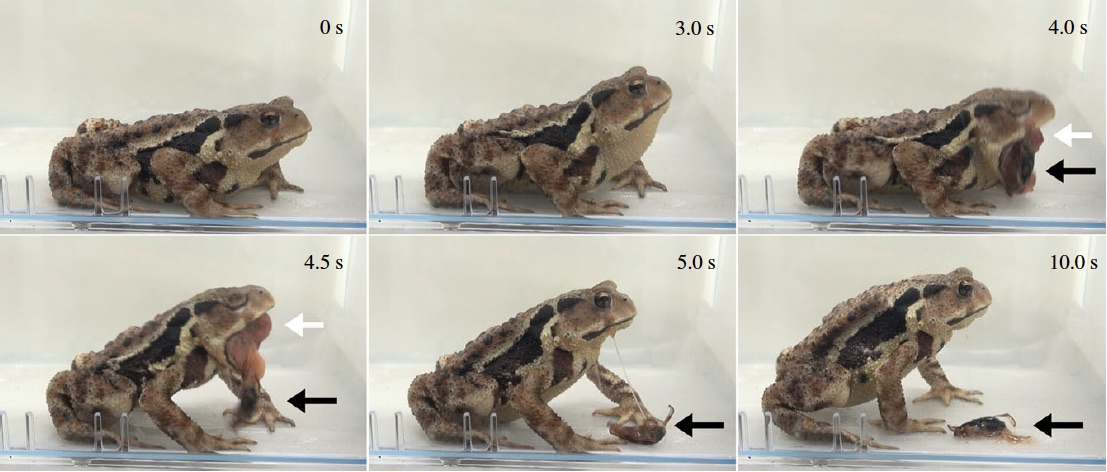

This hot, chemical spray is so powerful that it can prompt the toad to evert its stomach — that is, turn it completely inside out — so the amphibian can vomit out the beetle. At this point, the insect is covered with mucus from the toad's stomach, but still wriggly and, most importantly, alive, the researchers said. [Gallery: Out-of-This-World Images of Insects]

There are 649 species in the bombardier beetle tribe, but the defensive strategies of only a few are known. So, the researchers in the new study decided to take a closer look at P. jessoensis by observing exactly what happened to toads that ate the insects.

But first, the experiment required some fieldwork. The researchers collected 37 adult P. jessoensis beetles, 23 Bufo japonicus toads and 14 Bufo torrenticola toads from a forest's edge in central Japan.

Then, the puking began. The researchers gave each toad one beetle and watched what happened. Soon after the toads gobbled up the beetles, a chemical "explosion was audible inside each toad," the researchers wrote in the study. Not every beetle made it out alive, however.

Just 35 percent of the B. japonicus toads threw up, compared to about 57 percent of the B. torrenticola toads. It took from 12 minutes to nearly 2 hours for some toads to throw up, but most averaged just under 50 minutes to hurl. And once a beetle made it out, it was good to go.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"All 16 beetles that the toads vomited up were still alive and active," and 15 of those beetles lived for at least two weeks after the ordeal, the researchers said in the study.

What's more, the toxic cocktail was clearly the reason for the beetles' survival. When the researchers "treated" the beetles so they couldn't eject their spray, 100 percent of the B. japonicus toads ate the insects and about 85 percent of the B. torrenticola easily gulped down the critters.

Survivor beetles

An analysis revealed that size truly does matter, at least when trying to make toads upchuck. Larger beetles were more likely to survive than small beetles, and small toads were more likely to vomit than large toads, the researchers found. This is likely because "large beetles can eject more defensive chemicals than small beetles, [and] large beetles are more likely to survive the toad digestive system than small beetles [are]," the researchers wrote in the study.

As for the amphibians, "small toads have a lower toxic tolerance than large toads," the researchers wrote.

The investigators also found that the beetles fared better in the B. japonicus stomachs, with an 82 percent survival rate, compared to a 72 percent rate for B. torrenticola toads. It appeared that although B. torrenticola had a higher rate of vomiting, it also had more-potent digestive abilities than the other toad. [40 Freaky Frog Photos]

In Japan, the bombardier beetle lives around more B. japonicus toads than B. torrenticola toads, the researchers said. Perhaps, B. torrenticola has a lower tolerance for the beetles' surprising spray because that toad rarely encounters it, the researchers said.

The scientists noted that the experiments did not seriously harm or kill the toads, which were released back into the wild after the trials. The researchers couldn't, however, say the same for the beetles.

The study was published online Feb. 7 in the journal Biology Letters.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus