Gallery: Out-of-This-World Images of Insects

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Saddleback caterpillar

The saddleback caterpillar is one of the most colorful of all North American animals and lives in the eastern half of the United States. Like a stinging nettle, the bristles on its back prickle and burn anyone who touches them. In adulthood, the caterpillar changes into a small moth with dark chocolate-colored wings that have a few green spots.

Two-lined spittlebug

This insect leaves its spitlike mark in the grasslands of the eastern United States. Young two-lined spittlebugs often form a blob of liquid waste and mucous secretions on low-lying plants, which some people mistake for human spit.

Derbid planthopper

The derbid planthopper, an uncommon small insect that's been spotted in Maryland, Illinois and Wisconsin, live on woody fungi, but most people see them when they swarm around porch lights. The insects are relatives of leafhoppers.

Unicorn caterpillar

Smithsonian Institute entomology spokesman Gary Hevel found this unicorn caterpillar on a blueberry leaf in his backyard in the summer. The caterpillar's camouflage — in this case, the dead leaf — helps it escape predators before it turns into a prominent moth in the Notodontidae family.

Parasitic wasp

Native to China, the parasitic wasp parasitizes small beetles. Hevel remembers finding them in a dying plum tree in his backyard years ago. Eric Grissell, a Smithsonian curator of wasps at the time, thought it was a new species, but later found that it was a known insect in China. The two wrote a paper detailing its appearance, which was new to the record in the Western Hemisphere.

"It is quite important to record species in the United States, especially alien species, because insects play enormous roles in their environments, sometimes causing great destruction of food plants and ornamental plants," Hevel told Live Science in an email.

Giant leopard moth

With its distinctive black spots and circles smattered over its white wings, the giant leopard moth is one of the largest in the tiger moth family. Its abdomen has an unexpected splash of blue and orange color, Hevel said.

Click beetle

The click beetle aims to scare away predators with two large, fake eyespots behind its head. The beetle's true eyes are small and located at the base of the antennae, Hevel said.The beetle can make a loud clicking noise by snapping two sections of its thorax together, the University of Michigan reports.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Flat bug

It can be difficult to spy a flat bug because these dark gray insects live under dead tree bark, particularly in tree stumps, Hevel said. Their flatness helps them move around easily in these habitats.

Royal walnut moth

This large yellowish-brown moth is one of the largest moths in the United States, with a wingspan that measures between about 4 and 6.25 inches (10 and 16 centimeters). It begins as a 5-inch (13 cm) caterpillar known as the hickory horned devil, Hevel said.

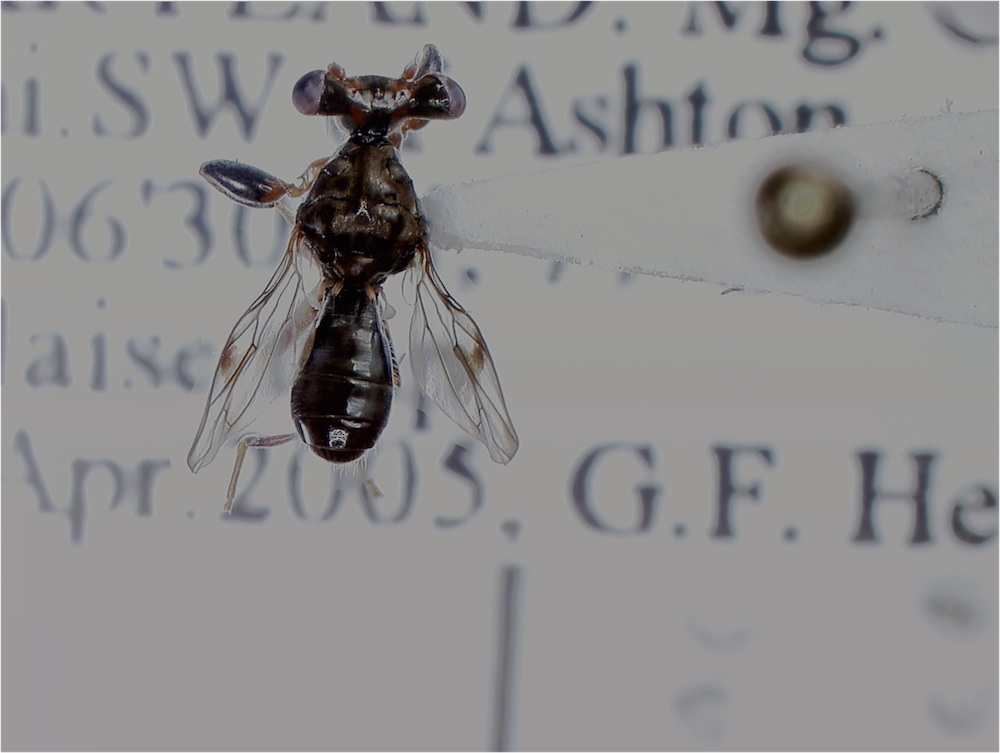

Stalk-eyed fly

Stalk-eyed flies are aptly named for eyes that, according to the species, sit at the end of short to long stalks coming out of their head. Some males have an eye span that is longer than their body, a study published in the journal cell found.

Amateur entomologists can find them on skunk cabbage, Hevel said.

Banded black and yellow caterpillar

This yellow and black caterpillar gives a surprise when disturbed. If it gets poked, a large, bright yellow organ emerges from the front end of its body. Eventually, these caterpillars turn into black swallowtail butterflies.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus