Tiny Dino-Era 'Night Mouse' Found Above Arctic Circle

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A tiny marsupial relative that lived in the twilight of the dinosaurs, as well as in literal twilight for much of the year, has been discovered in the Arctic.

The mouse-sized creature lived 69 million years ago on the northernmost landmass of its day, at the equivalent latitude of the northern islands of the Svalbard archipelago today. Its high latitude would have put it in total darkness for four months out of each year.

Scientists found the miniscule teeth and a jawbone of the animal on the side of a steep riverbank in Alaska. They dubbed the animal Unnuakomys hutchisoni to reflect its oft-unlit home range: In the indigenous Inupiaq language, unnuak, pronounced Oo-noo-ok, means "night." Mys is Greek for "mouse." [See Photos of the Arctic 'Night Mouse']

"We don't think about finding tiny marsupials at 85 degrees north latitude," said Jaelyn Eberle, the curator of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Colorado, Boulder Museum of Natural History and one of the discoverers of the new species.

Alaskan excavation

The teeth and bones of the "night mouse" have been popping out of the soil occasionally over decades of excavation along the Colville River in the North Slope of Alaska. It's an unusual place for excavations: Paleontologists have to wear hardhats while balanced on the steep riverbanks, because the banks periodically crumble and slough off dirt and rock into the river. The sound of these mini-avalanches is audible from the tents on the sandbanks where the researchers camp each night, Eberle said.

Paleontologist Patrick Druckenmiller of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, and colleagues have been excavating dinosaurs from the riverbanks for years. Over time, Druckenmiller told Live Science, the team has learned how to recognize thin sediment layers, less than 4 inches (10 centimeters) thick, which were deposited at the base of small Cretaceous streams. These layers tend to hold small, rare fossils, like mammal teeth and fish bones. [In Images: The Oldest Fossils on Earth]

Once the researchers find the particular layers, Druckenmiller said, they shovel them out wholesale into buckets. The clay and dirt are then washed out, and the paleontologists, along with their students and research assistants, sift through buckets upon buckets of the leftover chunky grains under microscopes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most of the mammal teeth, Eberle said, max out at about 0.06 inches (1.5 millimeters) in length. So far, though, Eberle and other researchers from several universities involved in the project have found about 70 U. hutchisoni teeth and a lower jawbone.

Tiny and toothy

That's enough to make an estimate of the size of the animal and guess at its diet. The mammal was part of a group called Metatheria, Eberle said, which includes today's marsupials. It weighed around an ounce, about the size of a mouse or small shrew, and its sharp teeth suggest that it may have feasted upon insects. Judging by the teeth, the researchers suspect U. hutchisoni may have been a bit like modern possums.

U. hutchisoni is the northernmost of its kin in the family Pediomyidae, Eberle said. Previously, the most northern site where this family of mammals was found was in northern Alberta, Canada. Today, the excavation site lies at about 70 degrees north latitude. In the Cretaceous period, given the movement of the continents, it would have been between 80 and 85 degrees, meaning the "night mouse" would have spent about 120 days out of every year in 24-hour darkness.

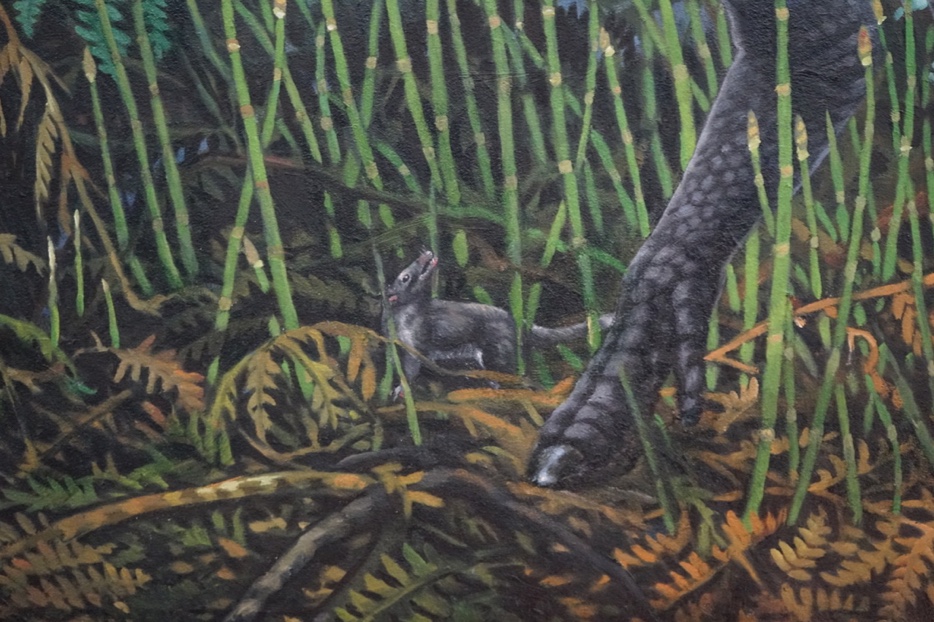

The climate 69 million years ago was a bit warmer than today, so the animal's habitat would have averaged around 43 degrees Fahrenheit (6 degrees Celsius). It would have been below freezing in winter, Eberle said, and cool in the summer. U. hutchisoni might have lived in underground burrows as an adaptation to the cold weather, she said. It would have scampered amidst conifer forests inhabited by duck-billed dinosaurs and smaller meat-eating relatives of Tyrannosaurus rex.

The larger research project, funded by the National Science Foundation, is dedicated to unraveling this ancient Arctic habitat, Druckenmiller said. So far, he said, both the mammals and the dinosaurs found in northern Alaska seem to represent unique species not found farther south.

"That's a pretty cool discovery, to know that we basically have a distinctive polar fauna during the age of dinosaurs," he said.

The newly discovered mammal species didn't outlast the dinosaurs, like some of the other small mammals of the Cretaceous did. Other mammals found in the same sediments are from groups that did survive, Eberle said, though those fossils have yet to be fully analyzed.

"Folks have hypothesized that being small and having the ability to potentially hide underground when a big meteorite comes along would have preadapted these guys to survival," she said.

The research was published Feb. 14 in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

- Photos: These Mammal Ancestors Glided from Jurassic Trees

- In Photos: Mammals Through Time

- Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

Editor's Note: This article was updated to indicate the fact that the "night mouse," which was supposed to be scampering at its master dinosaurs' feet in the illustration, in fact, is not there.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus