Bed Used in Hotel for 15 Years Turns Out to Be Henry VII’s Marriage Bed

An ornately carved oak bed that spent 15 years in the honeymoon suite of a hotel in Chester, in the United Kingdom, had a remarkable hidden history: Experts recently found that it is likely to be a long-lost royal marriage bed dating to the 15th century.

In it, the nuptial frolics of King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York celebrated the end of the Wars of the Roses (during which King Richard III died) and birthed England's famed Tudor dynasty.

The bed's former identity came to light after it was retired from the hotel and discarded in a parking lot. It was rescued by an antiques dealer who listed it as "a profusely carved Victorian four poster bed with armorial shields," according to a description from a symposium about the bed's history, held on Jan. 21 at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

When Ian Coulson, a restorer and dealer of antique beds, purchased the bed online in 2010, he discovered that the wood was far older than the seller suspected. What's more, the bed's embellishments hinted at royal origins, National Geographic reported. [Family Ties: 8 Truly Dysfunctional Royal Families]

The restored bed stands 9 feet tall (3 meters) and measures 6 feet long and 5 feet wide (2 by 1.7 m), according to representatives of The Langley Collection, to which the bed belongs.

Its four posts are tipped with carved lions, one of which is missing a tail. Carvings of crests, vines and heraldic shields cover the frame, and the headboard includes a triptych with a central panel of Adam and Eve, Coulson wrote in a blog post.

Clues in the varnished wood and in the quality and content of the carvings suggested to Coulson that this was a royal bridal bed, and that it belonged to Henry VII, Nat Geo reported. While the claim initially seemed far-fetched, Coulson spent the next nine years accumulating evidence of the bed's lofty origins; he and other experts presented their findings at the symposium.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fit for a king

When Coulson initially examined the bed, he found more damage to the sturdy oak than would reasonably be expected for a bed that had been made during the Victorian era, and the amount of oxidation in the bedposts would have taken centuries to accumulate, he wrote.

The faces in the Adam and Eve headboard carving resemble early portraits of Henry VII and his queen; and the figures are surrounded by fertility symbols — acorns, grapes and strawberries, historian Jonathan Foyle wrote in a leaflet describing the bed.

Meanwhile, emblems such as stars, shields, lions and roses carved into the bed frame were frequently associated with Tudor royalty; together, they matched the style of surviving Tudor beds from the 15th and 16th centuries.

"The self-evident age of the timber, the royal devices with the lack of other family insignia and the exquisite design and execution of the carving convinced me that this was a royal bed of Henry VII," Coulson wrote.

Sole survivor

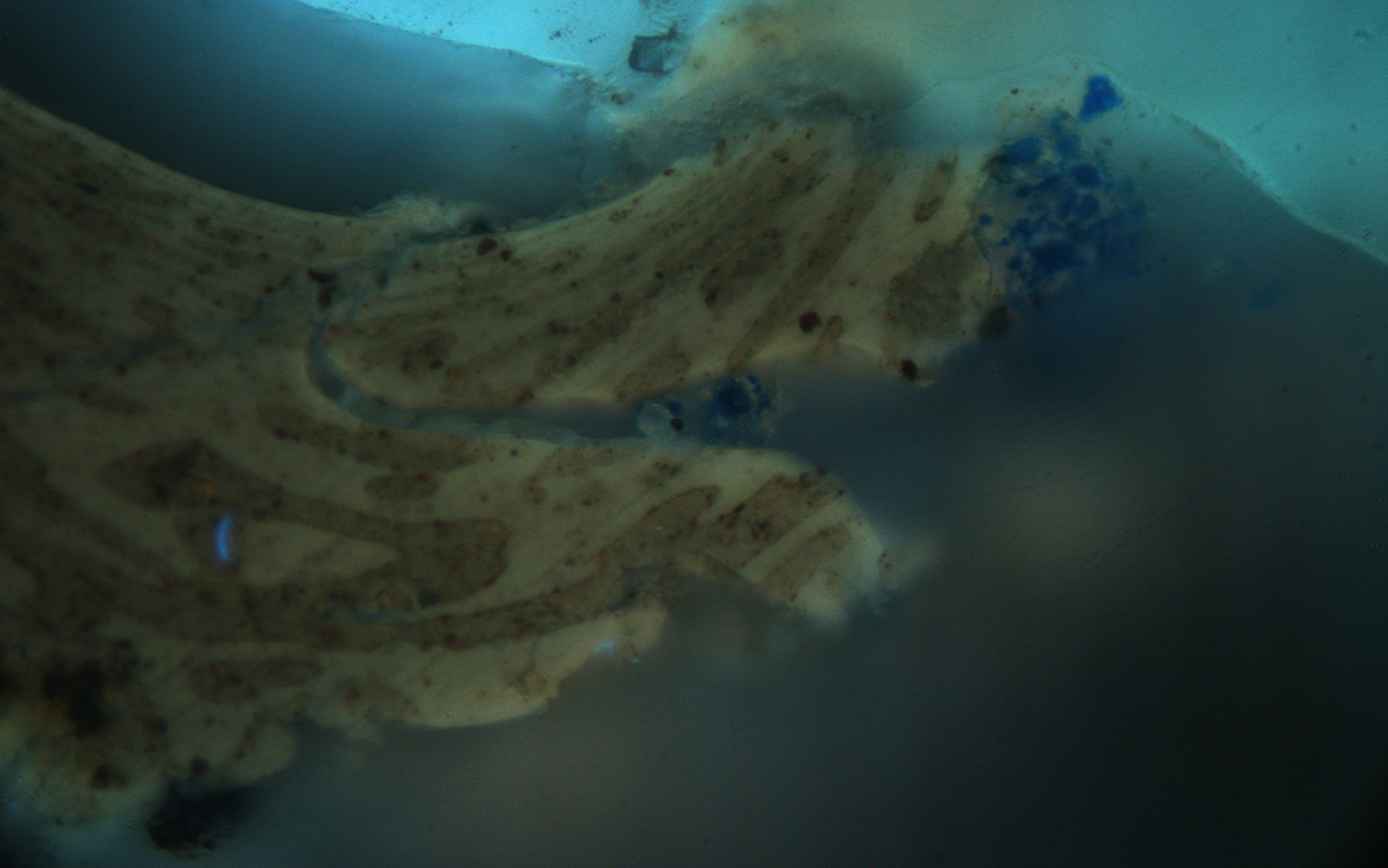

DNA analysis of the wood confirmed that it was oak from central Europe of the genetic variety known as Haplotype-7, found from southern France through Belarus, and all of it came from the same tree, according to the online news outlet Hexham-Courant. Samples of paint under the headboard varnish revealed flecks of ultramarine; this vivid blue medieval pigment was more precious than gold and likely would have been used only to decorate beds belonging to royalty, Coulson said.

The marriage of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York was a turning point in British history. The event united the rival houses of York and Lancaster and ended the 30-year conflict known as the Wars of the Roses, launching the British dynasty known as the house of Tudor.

The bed was likely installed in a ceremonial bedchamber in Westminster Palace for the enjoyment of the newlywed king and queen, following their wedding in Westminster Abbey on Jan. 18, 1486, Foley wrote in the leaflet.

Most of the Tudor belongings from that period were lost, burned up in fires set by anti-royalists under Oliver Cromwell during the 17th century; until now, the only known Tudor bed to have escaped burning was a headboard fragment that once belonged to Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves, the Hexham-Courant reported. However, Henry VII's bed is thought to have survived the fires set in Westminster because it was sent to Lancashire in 1495, according to The Langley Collection.

- Rooms from lavish Greenwich Palace uncovered (photos)

- In photos: Search for the grave of King Richard III

- Weighted blankets: How they work

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus