This Unknown Woman May Have Illustrated Elaborate and Sacred Medieval Manuscripts

Archaeologists recently identified what might be called the first evidence of "bluetooth."

Traces of ultramarine — a vivid blue pigment ground from the mineral lapis lazuli, mined only in Afghanistan and once as prized as gold — were detected in plaque coating the teeth of a woman who died in western Germany about 1,000 years ago.

Blue pigments were rare in medieval Europe, and ultramarine was the rarest and the most costly of them all, scientists wrote in a new study. This pigment was therefore used to illustrate only the most elaborate and expensive sacred manuscripts of the day.

Motes of pigment in the woman's teeth suggest that she may have helped illustrate some of those magnificent books, and are the first direct evidence linking ultramarine to a medieval woman. It adds to a growing body of evidence hinting that women were proficient scribes even during the earliest days of medieval book production, the researchers reported. [The 8 Most Grisly Archaeological Studies]

The woman was buried in an unmarked cemetery near a monastery complex that stood from the ninth century through the 14th century. Radiocarbon dating indicated that she lived around 997 to 1162. She was middle-age when she died, about 45 to 60 years old, and her burial location suggested that she was a pious woman, according to the study.

Further examination of her bones told the researchers that her overall health was good and that she did not perform prolonged hard labor.

Out of the blue

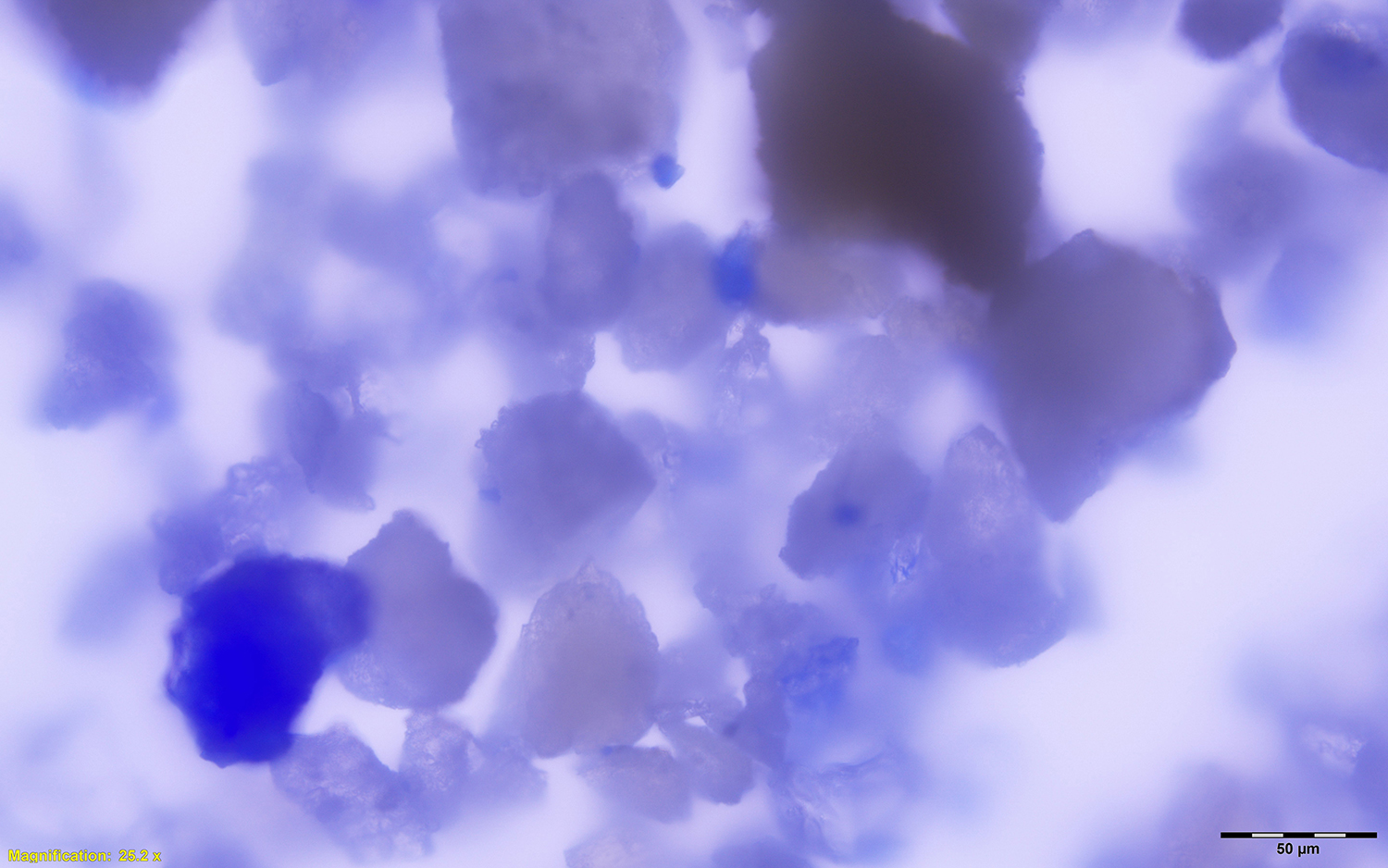

Blue particles were first detected in the woman's teeth during a prior study of dental calculus (or hardened plaque) conducted in 2014. For the new investigation, researchers dissolved samples of plaque, mounted the released fragments on slides and magnified the results.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the scientists examined the slides, they spotted more than 100 particles of "deep blue color" among the plaque. The particles were collected from plaque on different teeth from the front of the woman's jaw, near the lips. And these particles were likely distributed during multiple events that occurred over time, rather than all at once.

What's more, particle size and distribution were consistent with ultramarine pigment ground from lapis lazuli, the study authors wrote.

Researchers compared other blue minerals — including azurite, malachite and vivianite — to the particles to identify their source. The scientists also peered at the particles using a technique known as micro-Raman spectroscopy, which revealed their crystal structures and molecular vibrations. By comparing the medieval particles to modern samples of lapis, the researchers confirmed that the particles were, in fact, ground from lapis lazuli.

But how did blue pigment grains end up in the woman's teeth?

True blue

It's possible that she prepared the pigment for an artist and grains adhered to her teeth from airborne dust during the grinding process. Another possibility is that she consumed lapis powder for medicinal purposes, but this is less likely; while swallowing ground lapis lazuli was a common practice in the medieval Mediterranean and Islamic world, it was not well-known in Europe at the time, according to the study.

However, the most probable scenario is that the woman worked as an artist or scribe.

During Europe's medieval period, ultramarine was typically produced only in association with illuminated manuscripts, used for detailing the texts' intricate illustrations. Perhaps the woman contributed to those prized tomes and the pigment traveled to her teeth when she repeatedly licked her brush to draw the hairs into a fine point, the researchers said.

While sacred texts are generally associated with monasteries — and with male scribes — there is ample evidence that educated, aristocratic women who lived in monasteries (or similar religious communities) also crafted elaborate manuscripts, according to the study. However, records of female scribes from the early medieval period are scarce, and this unprecedented archaeological discovery "marks the earliest direct evidence for the use of this rare and expensive pigment by a religious woman in Germany," the researchers concluded.

The findings were published online today (Jan. 9) in the journal Science Advances.

- Top 10 Weird Ways We Deal with the Dead

- Photos: Medieval Skeletons Unearthed Near Saint's Tomb in England

- 25 Gruesome Archaeological Discoveries

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus