Ancient Aramaic Incantation Describes 'Devourer' that Brings 'Fire' to Victims

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A 2,800-year-old incantation, written in Aramaic, describes the capture of a creature called the "devourer" said to be able to produce "fire."

Discovered in August 2017 within a small building, possibly a shrine, at the site of Zincirli (called "Sam'al" in ancient times), in Turkey, the incantation is inscribed on a stone cosmetic container. Written by a man who practiced magic who is called "Rahim son of Shadadan," the incantation "describes the seizure of a threatening creature [called] the 'devourer,'" wrote Madadh Richey and Dennis Pardee in the abstract of a presentation they gave recently at the Society of Biblical Literature annual meeting. That event took place in Denver between Nov 17 and 21.

The blood of the devourer was used to treat someone who appears to have been suffering from the "fire" of the devourer, said Richey, a doctoral student in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. It's not clear whether the blood was given to the afflicted person in a potion that could be swallowed or whether it was smeared onto their body, Richey told Live Science. [Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts]

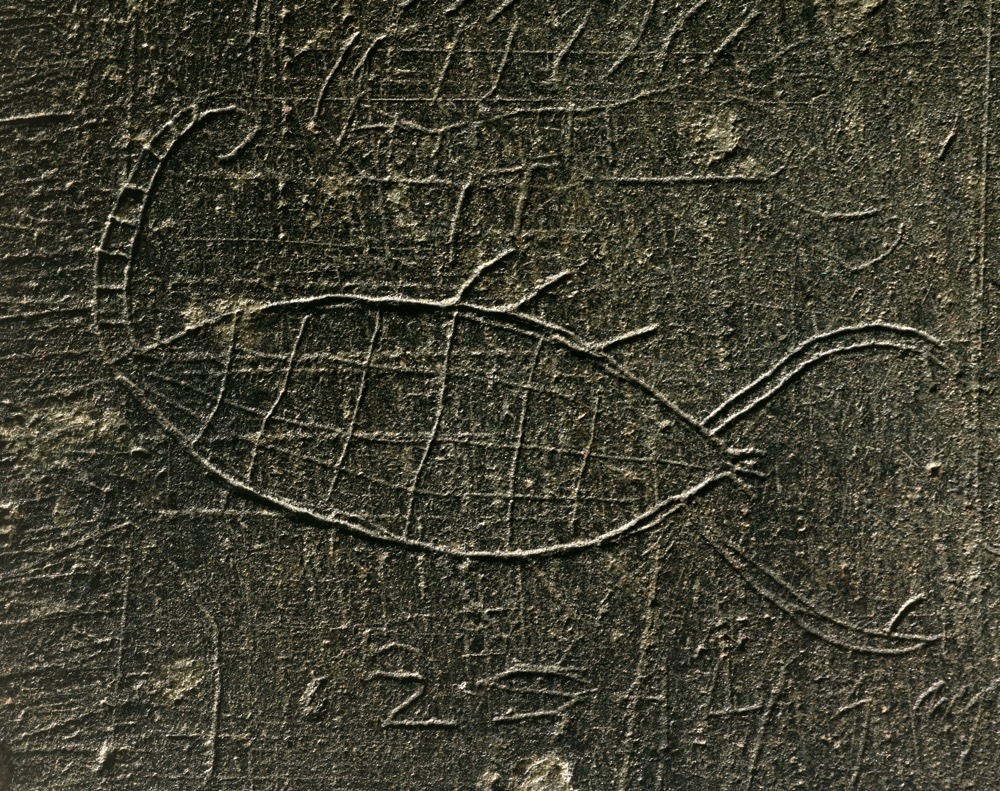

"Accompanying the text are illustrations of various creatures, including what appears to be a centipede, a scorpion and a fish," wrote Richey and Pardee, who is the Henry Crown professor of Hebrew studies at the University of Chicago, in the abstract. The illustrations are found on both sides of the cosmetic container.

The vessel would have originally stored makeup, and it appears to have been reused for the purpose of writing this incantation, said Virginia Herrmann, who is co-director of the Chicago-Tübingen Expedition to Zincirli, the team that uncovered the incantation.

What is the "devourer?"

The illustrations suggest that the "devourer" may actually be a scorpion or centipede; as such, the "fire" may refer to the pain of the creatures' sting, Richey told Live Science.

In fact, scorpions pose a hazard to archaeologists working at the site. "We always have to check our shoes and bags for scorpions on the excavation, even though most of the local scorpions do not have a very dangerous venom," said Herrmann, noting that shortly after the incantation was removed from the site, "one of our local workers was stung by a scorpion that had crawled onto his backpack that was sitting on the ground," and the archaeological team rushed to apply first aid.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Long life

Analysis of the incantation's writing indicates that it was inscribed sometime between 850 B.C. and 800 B.C., said Richey, adding that this makes the inscription the oldest Aramaic incantation ever found. However, the small building where the incantation was found appears to date to more than a century later, to the late eighth or seventh century B.C., Herrmann told Live Science. This suggests that the incantation was considered important enough that it was kept long after Rahim would have inscribed it, Herrmann said. [5 Ancient Languages Yet to Be Deciphered]

The incantation "had a significance that long outlived its original owner," Herrmann said. It was not the only artifact found in the small building that was kept long after it was created, she said, noting that a "statuette base of a crouching lion made of polished black stone with red inlaid eyes" was also discovered there. That lion figure appears to have been made in the 10th or ninth century B.C. The statuette base may have "once supported a metal figurine of a striding deity," Herrmann added.

Sam'al, where the building is located, was the capital of a small Aramaean kingdom that flourished between roughly 900 B.C. and 720 B.C., said Herrmann, noting that the city was seized by the Assyrians around 720 B.C.

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

- Move Over, 'Tomb Raider': Here Are 11 Pioneering Women Archaeologists

- Photos: Two Ancient Curses Discovered in Italy

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus