Yes, the 'Blob' Is Back. No, It Won't Wreak Havoc on East Coast Weather.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

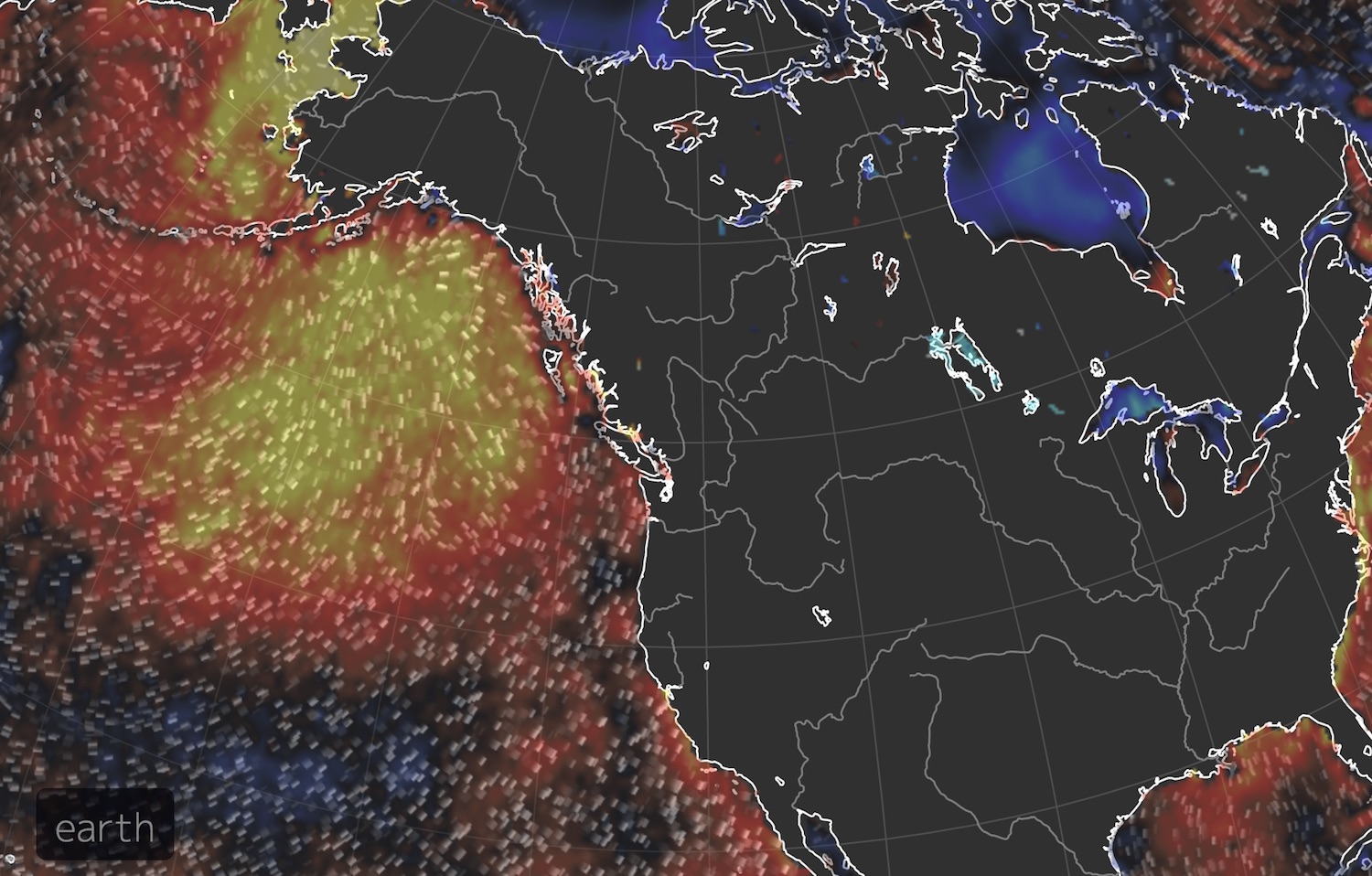

A returning patch of warm water in the Northern Pacific Ocean called "the blob" could spell wonky weather for the U.S. this winter. Or, that's what recent news reports suggest.

But as monstrous as its name sounds, "the blob" doesn't really have a major impact on the atmosphere and the weather beyond a couple hundred miles inland of the West Coast, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) told Live Science.

In 2015, the blob was blamed for a dry spell in the West and for prompting endless snow on the East Coast. But this is a questionable and "overly simple narrative," said Mike Halpert, the deputy director of the Climate Prediction Center at NOAA. [Weirdo Weather: 7 Rare Weather Events]

Unlike El Niño — a climate cycle sparked by unusually warm water in the tropics that can have a major impact on the atmosphere and weather patterns — a blob of warm water that far up in the Northern Hemisphere has "fairly minimal" effects on the atmosphere, Halpert said. "In the tropics where El Niño is, the ocean drives the atmosphere, but up in the northern latitudes like the south of Alaska, the atmosphere drives the ocean," Halpert said.

Where did the blob come from?

The current "blob" in the Northeast Pacific is a result of a mega-high-pressure zone that took shape in the atmosphere above it. This higher-than-normal pressureover the Gulf of Alaska, which most likely formed as a fluke, sprinkled Alaska with a mild and warm autumn, free of major storms. The absence of heavy winds and drops in temperature heated up the North Pacific waters.

It wasn't the blob that created a high-pressure zone; it was the high-pressure zone that created the blob.

That being said, the blob itself can have some significant effects on the temperature along the West Coast, according to Nicholas Bond, the state climatologist for Washington and research scientist with the University of Washington and the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory at NOAA, who was the first to coin the term "blob."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Prevailing winds from California to southeast Alaska blow from west to east," Bond said. In other words, they blow off the warm ocean onto land. In 2015, because of these winds, the coast was warmer than usual, he said. In June of that year, average monthly air temperatures were 1.8 to 10.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 to 6 degrees Celsius) warmer than normal in the Western states.

But the effects can be felt for only a couple hundred miles inland, Bond said. Besides impacting nearby air temperatures, the "blob" doesn't "seem to play a big role in terms of wind and pressure patterns themselves," he said.

The blob might give the ecosystem a fright

Even though it likely can't be blamed for intensifying a "snowy" winter on the East Coast, "the blob" can certainly wreak havoc on ecosystems and marine creatures, Bond told Live Science.

In 2015, the warmer water led to red tide algal blooms and lessened the availability of food and nutrition in that part of the ocean, causing fish to venture far from their typical homes and sea lion pups and seabirds to wash up on California's coast.

"The lingering effects of the original blob [in 2015] are still being felt in Alaska fisheries," Bond said. Some of the fish that hatched in those warm waters should be getting big enough to be in the fishery, yet they're not, he added.

The numbers of Pacific cod and a few other fish have been reduced because they encountered a decreased amount of food early in their life cycle, due to the poor nutrition available in the warm waters.

In 2015, the blob had warmed waters between 2 and 7 degrees F (1 and 4 degrees C) above average. Similarly, in the northern part of the Bering Sea, the current ocean temperatures are around 5.4 degrees F (3 degrees C) above normal, which will impact the "distributions of the fish and how well they do," Bond said.

But how much of an effect the blob will have in the coming months depends on how long it sticks around.

This high-pressure system will most likely shift and start to break down, causing stormier weather in the state, Bond said. If that happens, stormy weather will mix the warm waters with the surrounding cold waters, weakening the blob.

The current blob doesn't look as strong as it was in 2015, Bond said, "but you know Mother Nature has some tricks up her sleeve, and she doesn't always play fair," he said. "We'll just have to see."

Meanwhile, El Niño — the event that does have more of a predictable effect on the weather in the continental U.S.— is currently forming in the tropics. But it isn't a particularly strong one, according to a new winter-outlook report released by NOAA.

During the years when there is a strong El Niño, winter weather for the continental U.S. is easier to predict, Halpert said. So, currently, because the developing El Niño is weak, our "ability to predict this winter is not particularly strong."

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus