Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

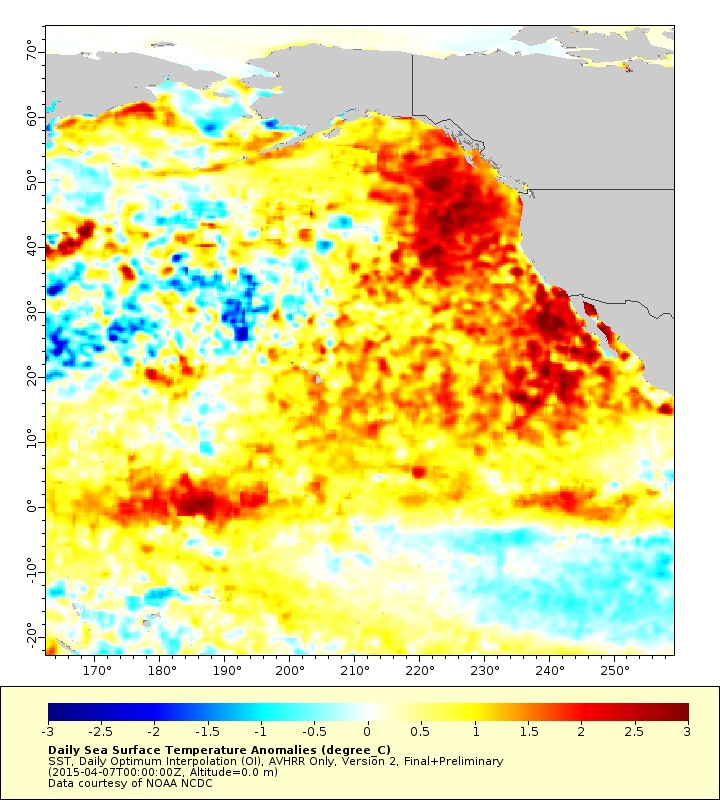

A warm blob of water lurking in the Pacific Ocean in 2014 and 2015 led to a spike in ozone levels across the western U.S., new research suggests.

The blob of warm water, which sat about 310 miles (500 kilometers) off the Oregon coast, was linked to a high-pressure system in the atmosphere that resulted in warm, calm air and sunny skies across nearly a quarter of the country, said study co-author Dan Jaffe, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington Bothell.

Those atmospheric conditions sped up the formation of ozone in the atmosphere, Jaffe added. (Ozone in the lower atmosphere is harmful to human health, while high in the atmosphere it forms a protective layer that shields the planet from harmful UV radiation.)

The finding suggests that these ocean patterns don't just mess with sea life; their effects may also reach far inland, he said. [The World's 10 Most Polluted Places]

Warm patch

The "blob" ― as meteorologists affectionately called the mass of warm water ― occurred from the winter of 2014 through the summer of 2015, when high sea-surface temperatures prevailed in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. The warmer waters — about 2 to 7 degrees Fahrenheit (1 to 4 degrees Celsius) higher than average for the region — spanned from the coast of Sitka, Alaska, to Santa Barbara, California, and came with a high-pressure system in the atmosphere that led to low wind speeds, fewer storms and sunnier skies.

The warm blob scrambled the food chain and brought a host of strange ecological effects: The toastier waters fueled some of the worst-ever toxic red tide algal blooms, and marine mammals died in droves as they struggled to find enough food in normally cold, food-rich waters, Jaffe said.

But the blob also had stark effects inland. In June 2015, for instance, the average monthly air temperatures were elevated between 1.8 and 10.8 F (1 and 6 C) relative to normal in the western U.S., researchers reported Wednesday (Feb. 15) in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. These regions also experienced more cloud-free, windless days.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jaffe and his colleagues had been tracking levels of ozone, a compound with three atoms of oxygen that can irritate the lungs, at the Mount Bachelor Observatory in central Oregon.

They found record-high levels of ozone above the Oregon peak. That spurred them to examine levels throughout the Mountain West. Sure enough, they found highly elevated levels of ozone throughout the region.

"When you looked at where the highest temperatures were and the unusual highest ozone levels were, you see an unusually good match," Jaffe told Live Science.

That made the team suspect the blob may have fueled the ozone levels. Ozone forms when hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides, which are emitted as pollutants from cars, undergo a complicated chemical reaction with sunlight in the atmosphere. Both sunlight and high temperatures fuel faster ozone-formation, whereas the wind blows away the basic building-block pollutants, making it harder to form ozone, Jaffe said.

When they investigated ozone levels throughout the West, they found areas with the hottest, most stagnant air also had highly elevated ozone levels, compared with historical averages. For instance, Salt Lake City and Sacramento, California, had unusually high levels, likely a combination of having high emissions of the base pollutants, as well as the optimal conditions for forming ozone, Jaffe said.

The new findings suggest the blob directly led to dangerous levels of ozone across the western U.S.

What's not known, however, is whether climate change will lead to more of these blobby weather patterns.

"We know it's getting warmer, and the question becomes how will ozone change in the future?" Jaffe said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus