Ancient 'Alien' Wasp Hijacked Fly Pupae, Ate the Flies Inside

Fossilized fly pupae are about as exciting to look at as a handful of dingy, stale Rice Krispies. But despite their humdrum appearance, fossil pupae can hold fascinating secrets inside; in some cases, they preserve deadly examples of insect parasitism.

Scientists recently investigated hundreds of fossil pupae — the inactive life stage between larva and adult — dating to the Paleogene period (about 65 million to 23 million years ago). They found unexpected stowaways inside: four new wasp species.

The wasps reproduced by parasitism, with females laying their eggs inside the bodies of pupating flies. Then, as the wasp larvae grew, they used the flies as a convenient, all-you-can-eat buffet. In most cases, the flies were entirely consumed, and the wasps died and became fossilized while still inside the flies' chrysalis shells. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

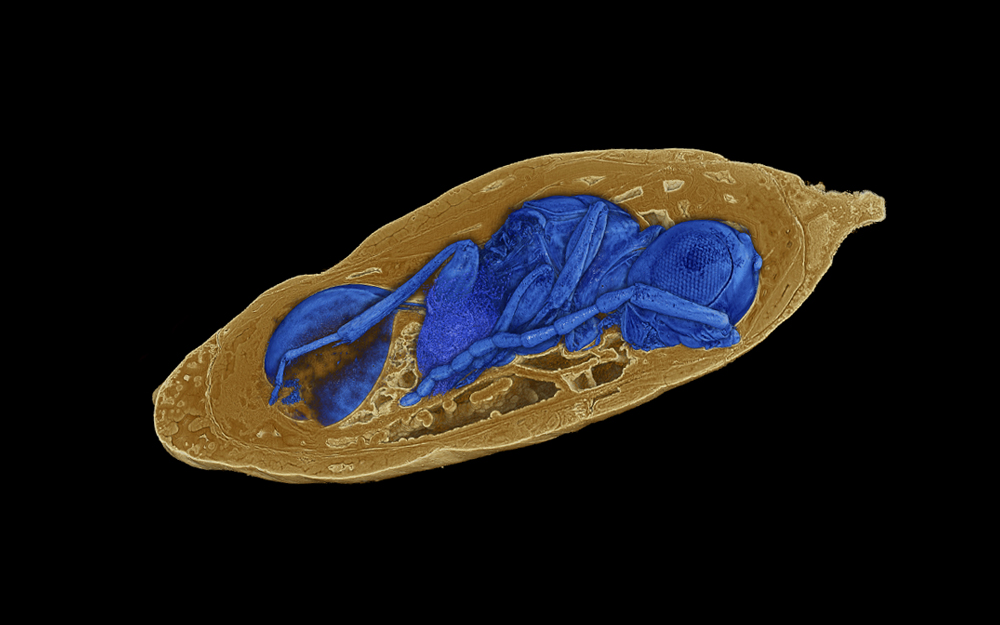

The researchers discovered the wasps by peering into pupae with X-ray scans, then reconstructing what they found inside with 3D computer modeling. They named the most common wasp Xenomorphia resurrecta — the first part of its name alludes to the terrifying, parasitic Xenomorph in the "Alien" sci-fi movies, while the second part of its name refers to the extinct species' "resurrection" through digital imaging, the scientists reported in a new study.

Many species of parasitic wasps are around today, targeting caterpillars, fly maggots, spiders and ladybugs as living meals for their ravenous young. One enterprising wasp species — named Euderus set, after the Egyptian god of evil and chaos — chooses targets that are in its own family, parasitizing other species of parasitic wasps.

But fossil evidence of parasitism in ancient wasps is exceptionally rare. Previously, the only example came from a single mineralized fly pupa from a site in Quercy, a region in southwestern France, dating to about 40 million to 30 million years ago, the researchers wrote.

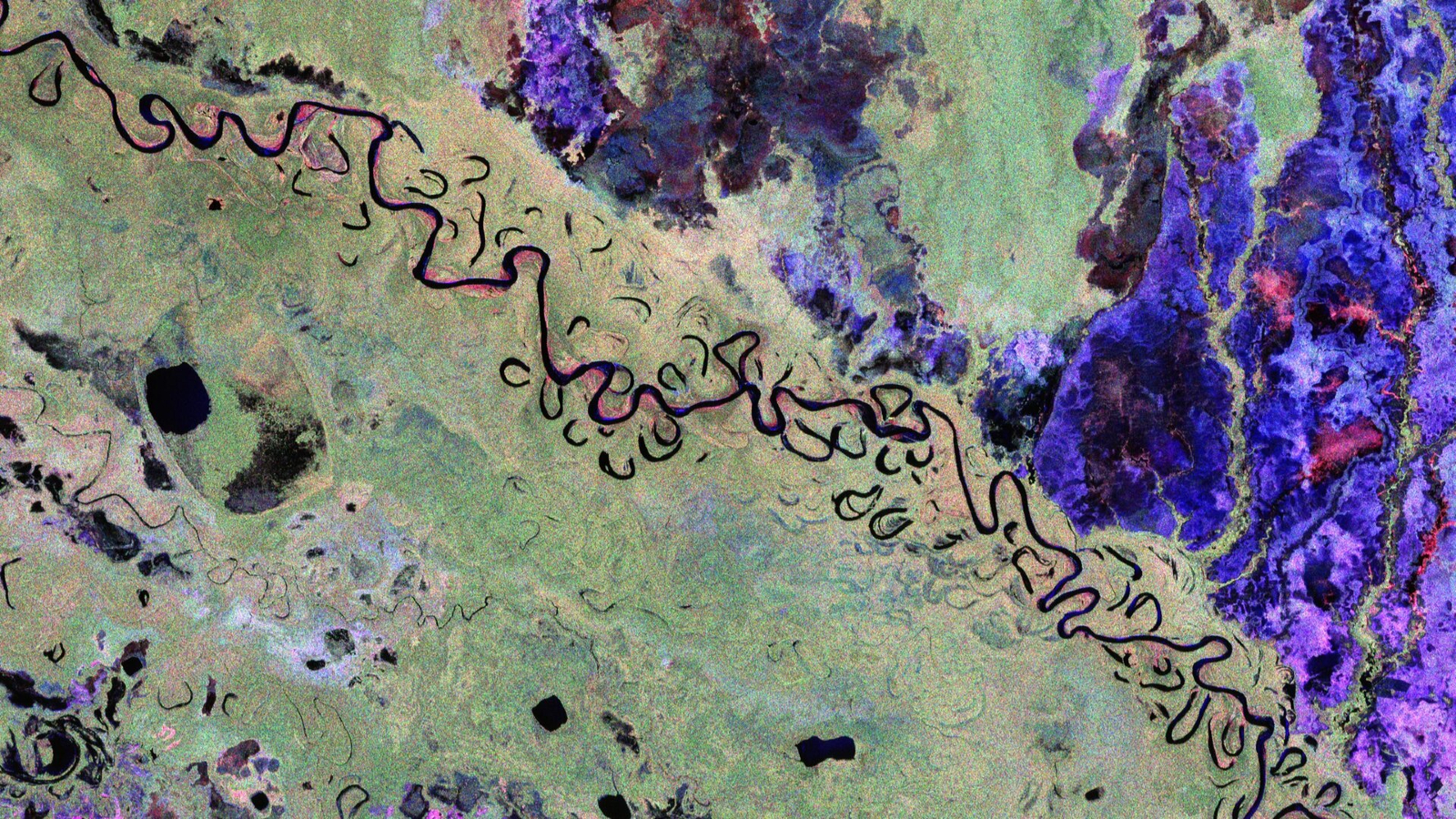

For the new study, the scientists examined 1,510 pupae, also from the Quercy site in France. They found 55 pupae that showed signs of being parasitized, and 52 pupae preserved the bodies of adult wasps. It's possible that the tough exoskeleton of adults was more resistant to decay than the softer tissues of their earlier developmental stages; this could explain why adult wasps were more abundant in the fossils, according to the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition to X. resurrecta, the scientists found more wasp species inside the fly pupae: Xenomorphia handschini, Coptera anka and Palaeortona quercyensis. Digital reconstruction of the fossilized wasps' delicate bodies pointed to subtle differences that defined the wasps as different species, and even hinted at the ecological niches they may have filled; the head and body shapes of C. anka and P. quercyensis suggested that they would have been better adapted to life on the ground than their Xenomorph-named cousins, the study authors reported.

The findings were published online today (Aug. 28) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus