How Scientists Created the Purest Drop of Water on Earth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

If cleanliness is next to godliness, then this is one divine droplet.

Researchers at the Vienna University of Technology announced yesterday (Aug. 23) that they have created the cleanest drop of water in the world.

This ultrapure water could help explain how self-cleaning surfaces, such as those coated with titanium dioxide (TiO2), become covered with a mysterious layer of molecules when they come into contact with air and water.

"We had four labs [around the world] studying this and four different explanations for it," said study co-author Ulrike Diebold, a chemist at the Vienna University of Technology. [The Mysterious Physics of 7 Everyday Things]

In the light of day

When TiO2 surfaces are exposed to ultraviolet light, they react in ways that "eat up" any organic compounds on them, Diebold told Live Science. This gives these surfaces a number of useful properties; for example, a TiO2-coated mirror will repel water vapor even in a steamy bathroom.

But leave them in a dark room too long, Diebold said, and the mysterious dirt forms.

Most of the proposed explanations for this involve some sort of chemical reaction with ambient water vapor. But Diebold and her colleagues applied the ultraclean water droplet to the surface and showed that water alone doesn't cause the film to appear.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Creating that superclean drop was a challenge, though. As Live Science previously reported, water very easily becomes contaminated with trace impurities, and perfectly pure water does not exist.

To get as close to perfectly pure as possible, Diebold said, her team had to design a specialized gadget that pushed water to its limits.

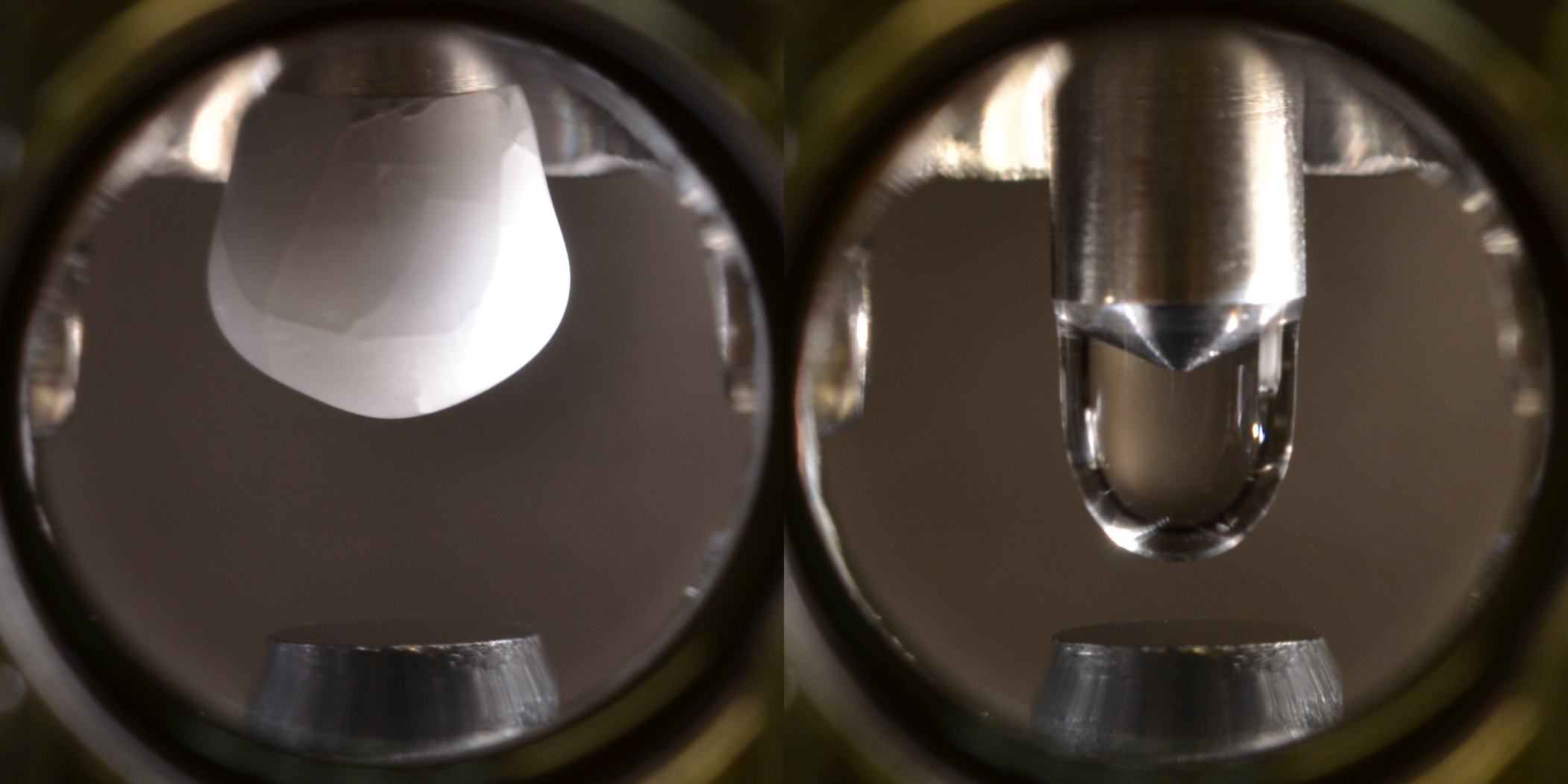

In one chamber of the device was a vacuum, with a "finger" hanging from its ceiling cooled to minus 220 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 140 Celsius). The researchers then released a thin, purified sample of water vapor from an adjacent chamber into the vacuum, so that the water formed an icicle at the tip of that finger. The researchers then allowed the icicle to warm up and melt, so that it dripped onto a piece of TiO2 below before quickly evaporating into the ultra-low-pressure chamber. Afterward, the TiO2 showed no sign of the molecular film that some researchers suspected came from water, the researchers reported today (Aug. 23) in the journal Science.

"The key is that neither the water nor the titanium dioxide had ever been exposed to air before," Diebold said.

Follow-up scans of TiO2 using microscopes and spectroscopes showed that the film wasn't made up of water or water-related compounds at all. Instead, acetic acid (which gives vinegar its sour taste) and formic acid, a similar compound, turned up on the surface. Both are byproducts of plant growth and are present in only tiny quantities in the air — but, apparently, there's enough of this material floating around to dirty a self-cleaning surface.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus