NASA Created a Rare, Exotic State of Matter in Space

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

NASA has cooled a cloud of rubidium atoms to ten-millionth of a degree above absolute zero, producing the fifth, exotic state of matter in space. The experiment also now holds the record for the coldest object we know of in space, though it isn't yet the coldest thing humanity has ever created. (That record still belongs to a laboratory at MIT.)

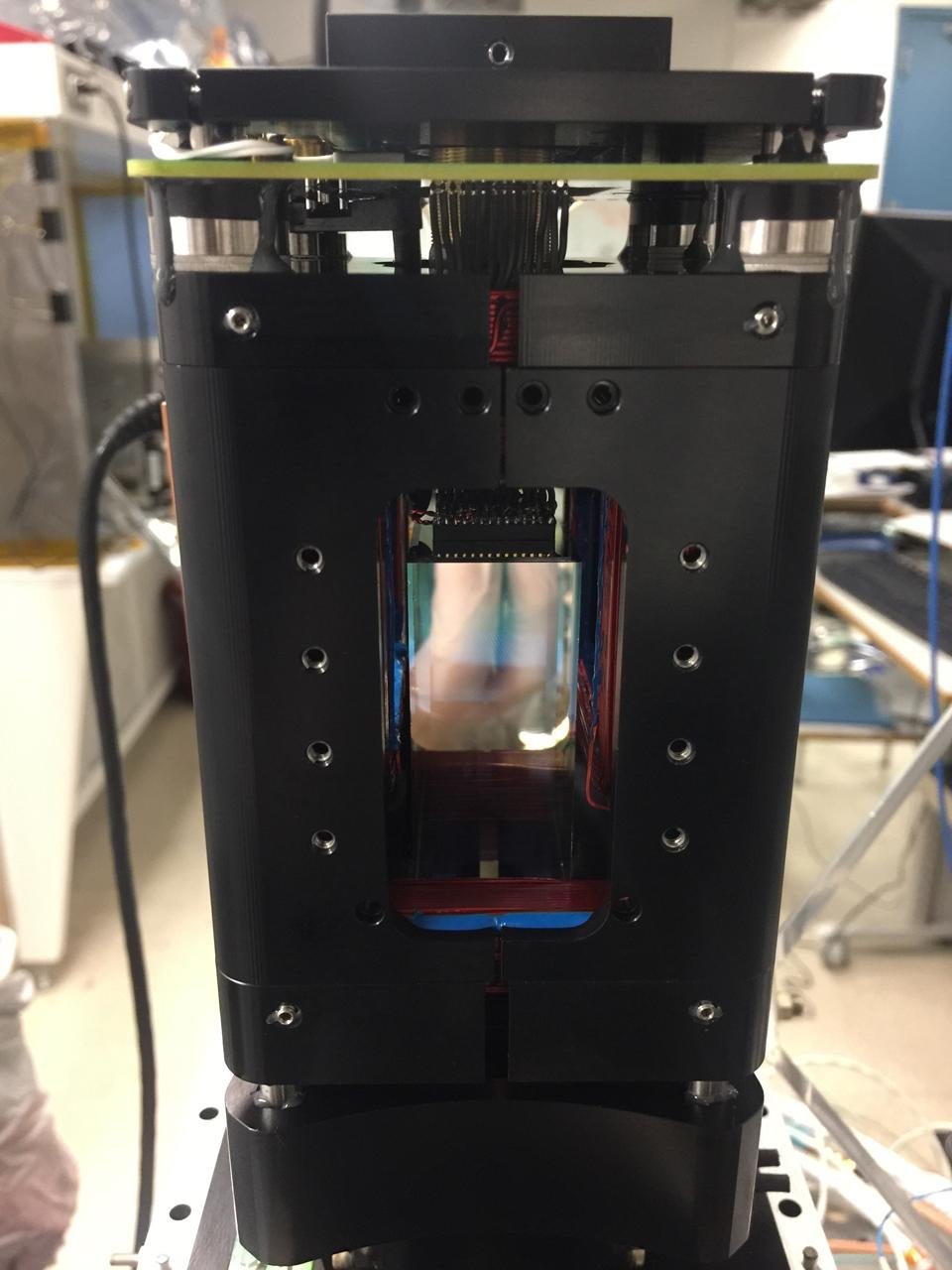

The Cold Atom Lab (CAL) is a compact quantum physics machine, a device built to work in the confines of the International Space Station (ISS) that launched into space in May. Now, according to a statement from NASA, the device has produced its first Bose-Einstein condensates, the strange conglomerations of atoms that scientists use to see quantum effects play out at large scales.

"Typically, BEC experiments involve enough equipment to fill a room and require near-constant monitoring by scientists, whereas CAL is about the size of a small refrigerator and can be operated remotely from Earth," Robert Shotwell, who leads the experiment from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in the statement.

Despite that difficulty, NASA said, the project was worth the effort. A Bose-Einstein condensate on Earth is already a fascinating object; at super-low temperatures, atoms' boundaries blend together, and usually-invisible quantum effects play out in ways scientists can directly observe. But cooling clouds of atoms to ultra-low temperatures requires suspending them using magnets or lasers. And once those magnets or lasers are shut off for observations, the condensates fall to the floor of the experiment and dissipate.

In the microgravity of the ISS, however, things work a bit differently. The CAL can form a Bose-Einstein condensate, set it free, then have a significantly longer time to observe it before it drifts off, NASA wrote — as long as 5 or 10 seconds. And that advantage, as Live Science previously reported, should eventually allow NASA to create condensates far colder than any on Earth. As the condensates expand outside their container, they cool further. And the longer they have to cool, the colder they get.

Originally published on Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus