Can You Really Get a Vasectomy Reversed?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

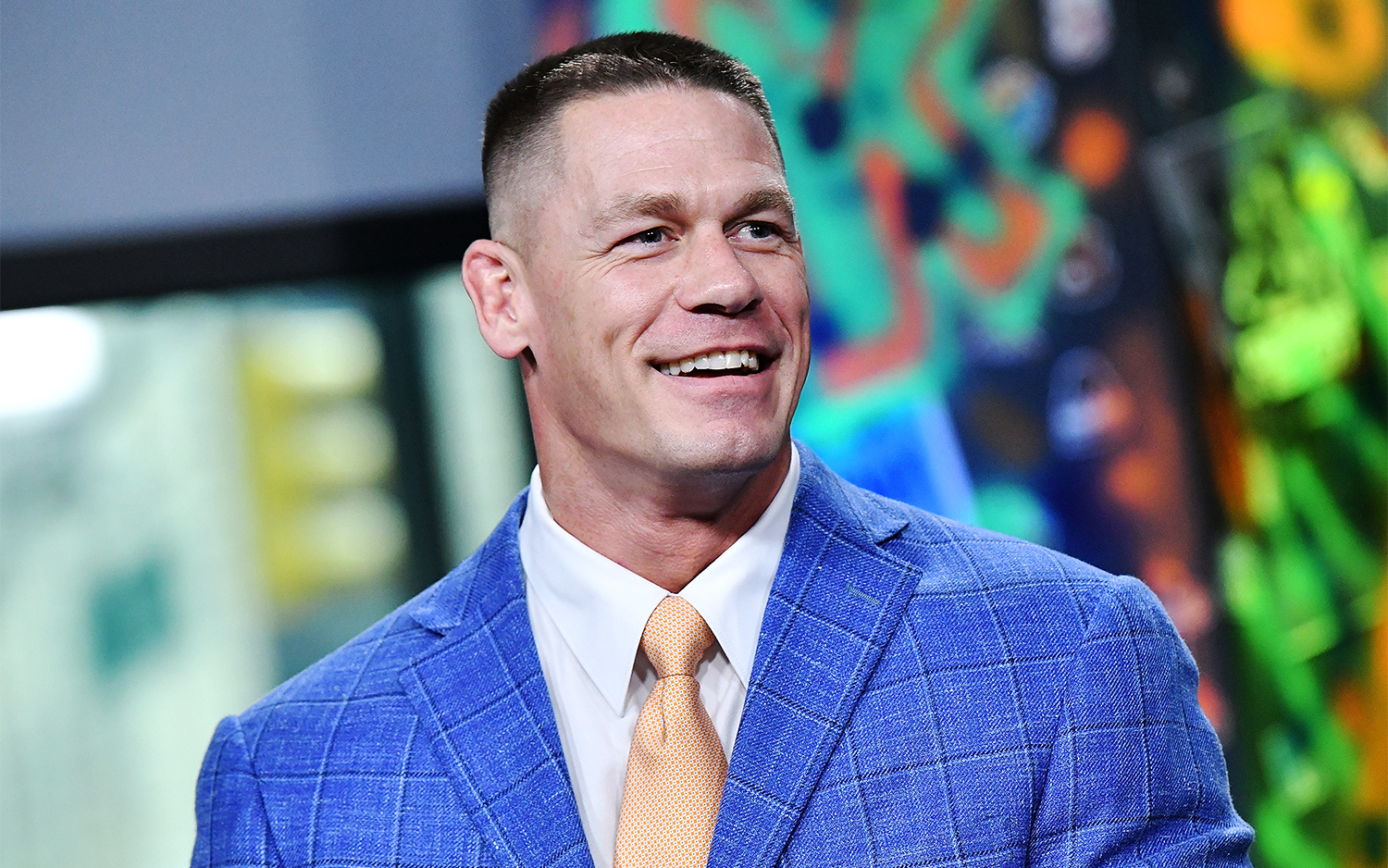

In a dramatic reality TV finale, actor and wrestler John Cena said that he's willing to reverse his vasectomy so he and his girlfriend can have children, according to People magazine. The announcement came on the midseason finale of the show "Total Bellas" on the E! network, which stars Nikki Bella, who is in a relationship Cena.

It's certainly a sweet sentiment, wanting to regain your ability to father a kid. But with a birth control method as severe as a vasectomy — in which the tube that transports semen is literally cut in half — is going back even possible? [Trying to Conceive: 12 Tips for Men]

Vasectomies are widely considered a permanent form of birth control, said Dr. Ajay Nangia, a professor and vice chair of urology at The University of Kansas Health System who specializes in the surgery. (Nangia is not involved in Cena's case.) During the procedure, doctors cut into the skin surrounding each testicle and clip out a small piece of the vas deferens, one of the small canals responsible for shuttling sperm out of storage and into the urethra, through which they normally leave the body. But with their pathway to the rest of the ejaculate fluids cut off due to a vasectomy, sperm can't leave the body.

Article continues belowAs irreversible as this sounds, undoing vasectomies is not only possible, but somewhat popular: About 6 percent of men end upwanting the process reversed, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. To "undo" a vasectomy, surgeons return to the site of the initial cut and bring together the two halves of the vas deferens using extremely delicate stitches. The thread used to reattach the tubes is thinner than a human hair, and the procedure requires an operating microscope that makes everything look 25 times larger, Nangia told Live Science. "It's like putting two tips of a pin together."

The process described above is the most straightforward approach to reversing a vasectomy. However, the procedure may sometimes be more complicated.

For example, if the original vasectomy removed a large section of the vas deferens — 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) instead of the typical 0.4 inches (1 cm) — it might be harder to stretch the tubes enough to close the gap, Nangia said.

The procedure can also become more complex if the surgeon sees a toothpaste-like buildup in the cut tube. That means the original surgery caused some blockage. If the surgeon can't remove this blockage, the doctor may have to attach one half of the vas deferens to a different sperm tunnel and reroute the ejaculation path, Nangia said. In other words, the two halves of the vas deferens wouldn't be re-attached where they were originally cut.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Reversing a vasectomy is only one part of the equation, however. The goal of the reversal is to be able to conceive naturally. [Future of Fertility Treatment: 7 Ways Baby-Making Could Change]

So, the ultimate question, is how many of these reattachments end in pregnancy?

Certain factors — such as scarring from the procedures, how long ago the original cut happened and the use of hormonal supplements, including testosterone — can reduce the number of sperm in the ejaculate, Nangia said. And if there are fewer sperm in each ejaculation, the odds of pregnancy can also depend on the partner's fertility. All these elements explain why the success rate for men who have reversed vasectomies falls somewhere between 40 and 90 percent, according to the Mayo Clinic. Or, more precisely: about 90 percent of reversals resulted in sperm making it through the final stretch, while 50 percent ended in pregnancy, according to one of the only studies that’s given the odds a close look.

Simply put, there's a good chance that a man who vows to reverse his vasectomy will be able to follow through on his promise. For men who have vasectomy and are unable to conceive naturally after the operation, in-vitro fertilization, with sperm retrieved from the man, is another possible option.

And while he's trying to get a family started, contraceptive researchers might have finally reached the next frontier of sperm blocking: glue. As Nangia put it, vasectomy surgery hasn't changed much in the last 30 to 40 years, but "everyone is looking for the holy grail of a glue that can block [the tubes] without [the need for] cutting," he said. (One such "glue" was successfully used to prevent pregnancy in monkeys in a 2017 study.)

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus