This 240-Million-Year-Old Reptile Is the 'Mother of All Lizards'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

HBO's "Game of Thrones" features a "Mother of Dragons," but a fossil that's hundreds of millions of years old was recently identified as the "mother of all lizards" (and snakes, too).

This ancient lizard was the direct ancestor of approximately 10,000 species alive today that have inhabited the planet for more than 240 million years.

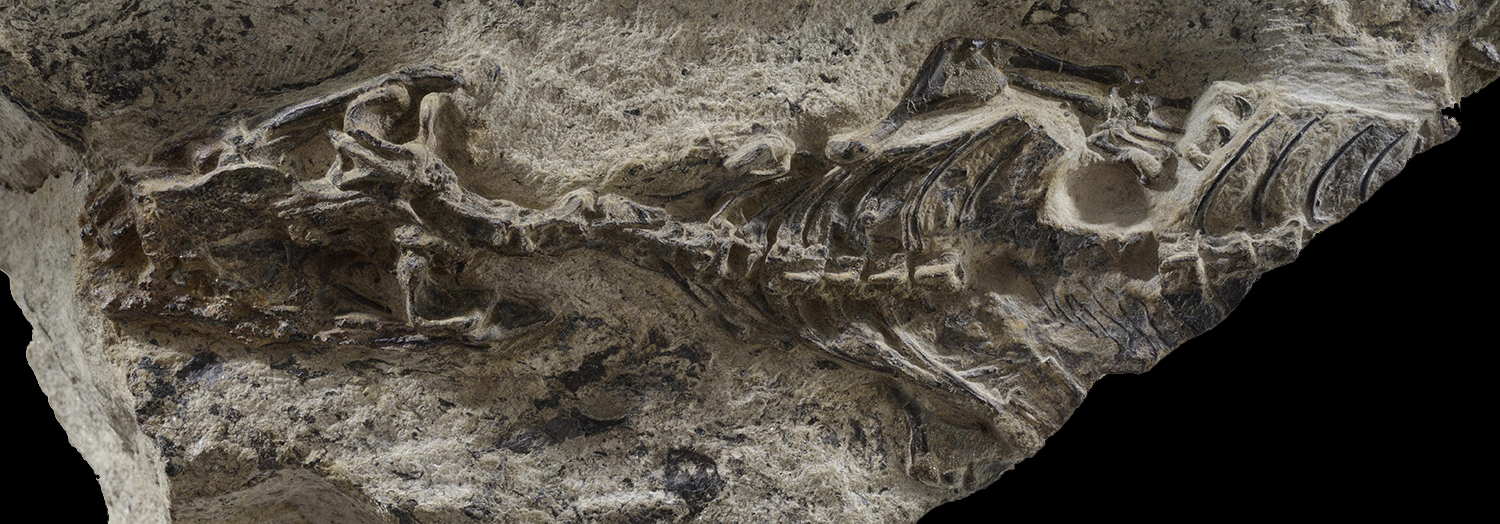

Paleontologists initially described the tiny reptile, Megachirella wachtleri, in 2003. But recent scans revealed features in the fossil that were hidden, enabling scientists to identify Megachirella as the oldest known ancestor in the squamate lineage — the reptile group that includes lizards and snakes.

Megachirella, which predates the fossils previously thought to belong to the earliest squamates by around 75 million years, bridged the gap between the oldest known squamates and the estimated origins of this reptile group derived from molecular data, researchers reported in a new study. [In Photos: Amber Preserves Cretaceous Lizards]

The Megachirella fossil was found in the Alps in northern Italy. It was estimated it to be about 240 million years old and scientists thought it belonged to a lepidosaur, a type of primitive reptile. But certain lizard-like features hinted that the fossil might provide valuable and unique clues about squamates, lead study author Tiago Simões, a doctoral candidate in biological sciences at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, told Live Science in an email.

"It deserved further attention — especially in the form of CT [computed tomography] scanning — to provide greater anatomical details and an improved data set, to understand its placement in the evolutionary tree of reptiles," Simões said.

The researchers used CT scans to build 3D computer models of the fossil reptile, and found a number of features linking Megachirella to squamates. Two of those features were unique to the squamate group: a part of the braincase and a collarbone structure. Together, those elements identified Megachirella as "the first unequivocal squamate from the Triassic," according to the study published online today (May 30) in the journal Nature.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Molecular and skeletal clues also indicated that geckoes, rather than iguanians (which includes iguanas, anoles and chameleons), made up the earliest squamate group to arise, the researchers reported.

Their evidence provided a critical and "really satisfying" missing piece of an evolutionary puzzle, by providing fossil evidence to support what molecular data suggests about squamate origins, Chris Raxworthy, curator-in-charge of the Department of Herpetology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, told Live Science.

"Scientists always love it when we see different types of data coming up with the same answer," said Raxworthy, who was not involved in the study.

However, a large gap persists in the fossil record between Megachirella, which lived 240 million years ago, and other fossil squamates that appeared no earlier than 168 million years ago. This leaves much to be unraveled about the diversity of these ancient snakes and lizards and what they may have looked like, Simões said.

"What we are discovering is the tip of the iceberg, and much further work needs to be done to understand the early evolution of squamates," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus