Rachel Carson: Life, Discoveries and Legacy

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

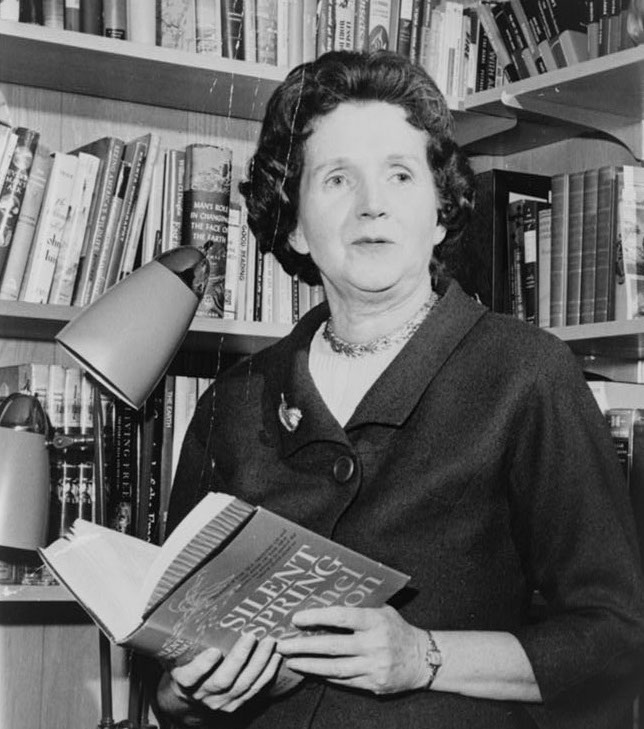

Marine biologist and writer Rachel Carson is hailed as one of the most important conservationists in history and is recognized as the mother of modern environmentalism. She challenged the use of man-made chemicals, and her research led to the nationwide ban on DDT and other pesticides. Her environmental movement also eventually led to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), according to the National Women's Museum.

"The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction," Carson said. She also famously stated, "But man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself."

Early Life

Rachel Carson was born on May 27, 1907, in Springdale, Pennsylvania, and grew up on a 65-acre farm. As a child, she spent her days exploring nature and writing. Her first work was published in a children's magazine when she was 10 years old. This upbringing instilled in her first-hand knowledge of nature and wildlife that spurred her into her life pursuits. "In every outthrust headland, in every curving beach, in every grain of sand there is the story of the earth," said Carson.

Originally determined to be a writer, Carson changed her major from English to biology in college. In 1929, she graduated from the Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham College). She then went on to do graduate work at Johns Hopkins University (which was almost unheard of for women at the time) and had her fellowship at the U.S. Marine Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. During her postgraduate studies she taught at the Johns Hopkins summer school. Carson then began teaching at the University of Maryland for five years.

Contributions to science

After the five-year stint, Carson joined the Bureau of Fisheries in 1935. One of her first duties was to create a series of seven-minute radio programs about marine life. They were named "Romance Under the Waters."

In 1936, she became one of only two women employed with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Bureau at a professional level, according to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, eventually becoming the editor-in-chief of the service's publications. She worked there until 1952. Carson also helped the government during World War II by investigating undersea sounds to assist the Navy in developing submarine detection.

While working for the government, she penned many articles that were published by the Baltimore Sun. She also wrote her first book, "Under the Sea-Wind," published in 1941. It was a scientific book on marine life, but it was written so that the average person could understand.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 1951 she published her second book, "The Sea Around Us," according to Encyclopedia Britannica. This book became an immediate best-seller and made her a wealthy woman. The book won a National Book Award, stayed on The New York Times' best-seller list for 81 weeks and ended up being translated into 32 languages. In 1955, Carson's third book, "Under the Sea," was published.

Carson spent the 1950s researching the effects of pesticides on the food chain across the United States and Europe with the help of Shirley Briggs, editor of an Audubon Naturalist Society magazine called Atlantic Naturalist, and Clarence Cottam, another former Fish and Wildlife Service employee.

This work culminated in her book "Silent Spring," which The New Yorker was published as a serial in 1962. It took her four years to write, according to Natural Resources Defense Council.

In the book, she explained why the use of pesticides was detrimental, paying particular attention to the effects of DDT. Carson asked the important question: do humans have the right to control nature? She also introduced the concept that planet Earth can only sustain pollution levels for a certain amount of time.

An expert from "Silent Spring":

One of the most significant features of DDT and related chemicals is the way they are passed on from one organism to another through all the links of the food chains. Fields of alfalfa, say, are dusted with DDT; meal is later prepared from the alfalfa and fed to hens; the hens lay eggs that contain DDT. Or the hay, containing residues of from seven to eight parts per million, may be fed to cows. The DDT will turn up in the milk in the amount of about three parts per million, but in butter made from this milk the concentration may run to sixty-five parts per million. During the process of transfer, what started out as a very small amount of DDT may end as a heavy concentration. The poison may be passed on from mother to offspring. The presence of insecticide residues in human milk has been established by Food and Drug Administration scientists.

The book earned her a presidential commission, giving her thoughts great credibility in the scientific world. Chemical companies tried to discredit Carson as a communist or hysterical woman. Despite their efforts, around 15 million viewers tuned in to the CBS Reports TV special on April 3, 1963, entitled "The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson."

Later, Carson was asked to testify before a congressional committee about the effects of pesticides. This led to the banning of DDT. She received medals from the National Audubon Society and the American Geographical Society. Carson also was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters, according to the National Women's Museum.

Impact

Carson died of breast cancer on April 14, 1964, in Silver Spring, Maryland. Sadly, she wasn't able to see the environmental revolution created by "Silent Spring," such as the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 or the Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge in Maine in 1966.

Carson once stated in a television interview, "man's endeavors to control nature by his powers to alter and to destroy would inevitably evolve into a war against himself, a war he would lose unless he came to terms with nature."

Additional Resources

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus