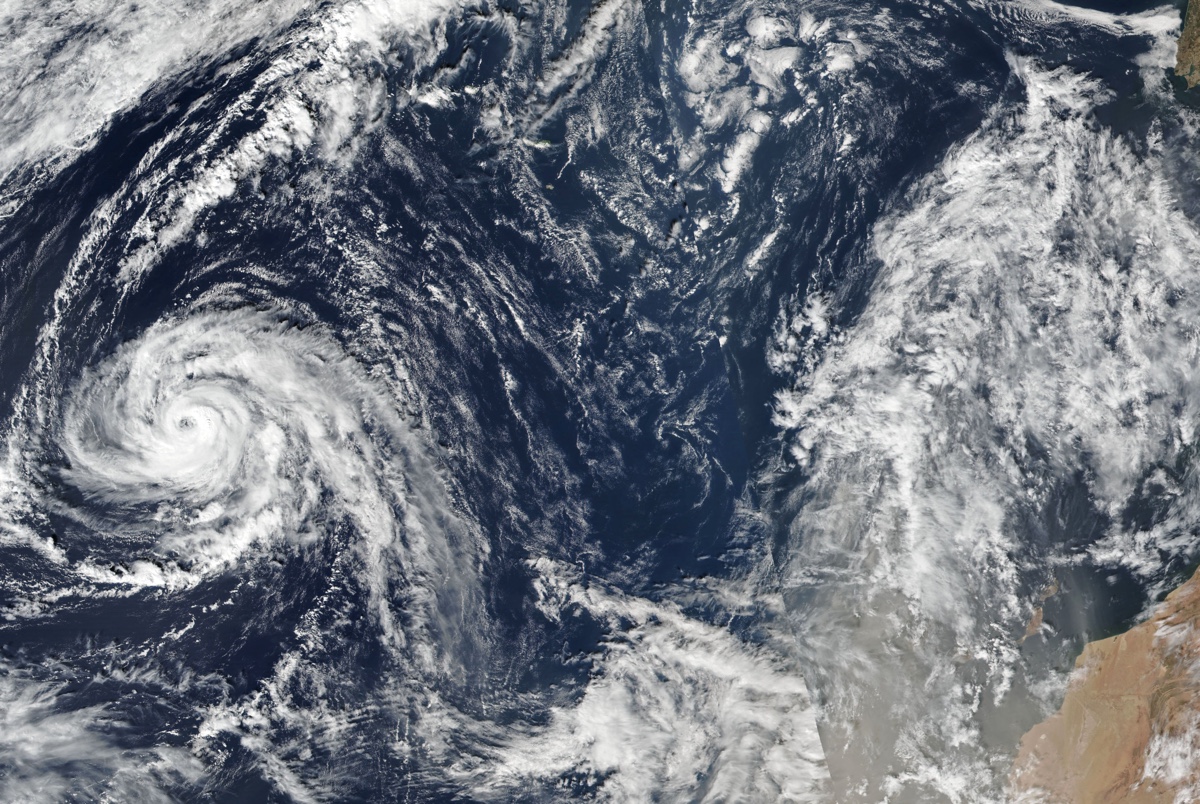

Hurricane Ophelia on Rare Course Toward Ireland, U.K.

As if the 2017 hurricane season weren’t already notable enough, now Hurricane Ophelia is on a rare track toward Ireland and the British Isles. While it will no longer be a tropical system by the time it reaches them, it could still bring rain, stormy seas and winds gusting up to 80 mph (129 km/h).

Ophelia is the 10th hurricane of a very busy season, with storms that have broken numerous records, from the 40 to 60 inches (100 to 150 centimeters) of rain Hurricane Harvey relentlessly dumped on the Houston area to Hurricane Maria — the first Category 5 storm to hit the Caribbean island of Dominica head-on.

The 2017 season has contained more days with a Category 5 hurricane than any other year on record, Michael Lowry, of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, tweeted. With Ophelia, the season becomes only the fourth on record to see 10 hurricanes form in a row, according to Phil Klotzbach, a hurricane researcher at Colorado State University.

While Ophelia isn’t a blockbuster storm like Irma or Maria, it has its own claims to fame. With its 100-mph winds, it is the strongest storm to form so far east in the Atlantic Ocean on record, Klotzbach tweeted. A Category 2 hurricane hasn’t developed that far north and east since 1992, Eric Blake, a forecaster with the National Hurricane Center, tweeted.

Ophelia has been able to flourish, not only because of warmer-than-normal ocean water, but also thanks to colder, upper-air temperatures.

“That combination allowed the storm to strengthen more than would be expected” because the atmosphere was more unstable, Klotzbach told Live Science in an email.

The course Ophelia is following is also fairly unusual, though not unprecedented.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hurricane Debbie struck Ireland in 1961, though it’s unclear whether it was still a tropical system or had transitioned into what is called an extratropical cyclone. Tropical cyclones have a warm core and a symmetrical circulation, whereas extratropical systems are driven by temperature differences across a weather front and have a comma shape.

Systems that do reach Ireland and the U.K. tend to be ones that have undergone that tropical-to-extratropical transition.

“We’ve seen direct impacts from core remnants of tropical cyclones impact Ireland and the U.K. before; most notably Ex-Charley (1986) and Ex-Katia (2011),” Steven Bowen, director of impact forecasting at the reinsurance company Aon Benfield, said in an email. “These types of scenarios are rare but not entirely unprecedented.”

A 2013 study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters suggests that Western Europe could see more storms with hurricane-force winds as warmer waters in the eastern Atlantic, fueled by rising global temperatures, expand the prime area of hurricane development and make it easier for storms to maintain their strength and tropical characteristics by the time they reach Europe.

Europe does see storms with hurricane-level winds that are purely extratropical in origin, many of which have caused considerable damage and financial losses, Bowen said.

Ophelia is expected to transition to an extratropical system as it moves toward Ireland and over cooler ocean waters and interacts with another low-pressure system.

Because Ophelia’s exact track is still uncertain, so is its potential impact. For Ireland, “storm force winds, heavy rain and high seas are threatened,” according to Met Éireann, the Irish Meteorological Service.

The U.K. Met Office, the national meteorological service, warns of wind gusts of around 50 to 60 mph (80 to 97 km/h), with some possibly higher gusts in certain areas of Northern Ireland and the west coasts of Scotland, Wales and England on Monday. Winds will then be concentrated in Northern Ireland, southern Scotland and northern England on Tuesday.

Those winds will whip up seas and could cause some power outages and travel disruptions, the Met Office said.

Original article on Live Science.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus