11 Hidden Secrets in Famous Works of Art

Introduction

There's often more to a picture than meets the eye, and many of the world's most famous artworks have secrets hidden beneath the surface.

Several famous paintings are known to cover older works by the artist that can now be detected by scientific techniques like X-ray fluoroscopy, revealing the original paintings and drawings that would otherwise be lost to history. In other cases, works of art feature cryptic clues placed by the artist, or contain curious resemblances — and some have even sparked popular conspiracy theories.

Here are 11 hidden secrets in famous works of art.

The Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck

The Arnolfini Portrait by the Dutch painter Jan van Eyck is thought to portray an Italian merchant named Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife, who lived in the Flemish city Bruges.

The painting is celebrated for its vivid and detailed representations of the couple and their surroundings, and the precise geometry of its composition, which includes an intricate reflection of the scene in a framed circular mirror hanging on the wall of the room.

The details of the painting have fueled many theories about its hidden symbolism, from the way the couple is joining hands, to the meaning of the small dog, the carelessly placed pairs of shoes, and the single lit candle in the chandelier. The artist's signature also appears as graffiti on the wall of the room: "Jan van Eyck was here, 1434."

The circular convex mirror on the wall near the center of the painting reveals an intricate reflection of the room as the scene was painted — including two additional figures standing beside the doorway, one whom may be the artist himself. It's not known if van Eyck used a real convex mirror to paint the scene from behind, but the curved distortions of the image are almost optically perfect, experts have said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A contentious theory from the 1930s holds that the scene is a representation of the marriage of the couple, and that the mirror image and van Eyck's dated signature are designed to serve as a legal record of the marriage, including the two witnesses required to be present. But, this theory now finds little favor with most art historians and with the curators of the National Portrait Gallery in London, England, where the painting is now on exhibit.

The distinctive Arnolfini Portrait is often referenced and parodied in popular culture, including a Muppet version featuring Kermit the Frog and Miss Piggy. In Ridley Scott's 1982 science-fiction movie "Blade Runner," bounty hunter Rick Deckard (played by actor Harrison Ford) find clues about the androids he is chasing by zooming in on the reflection in a circular, convex mirror that hangs on the wall of a room in a photograph.

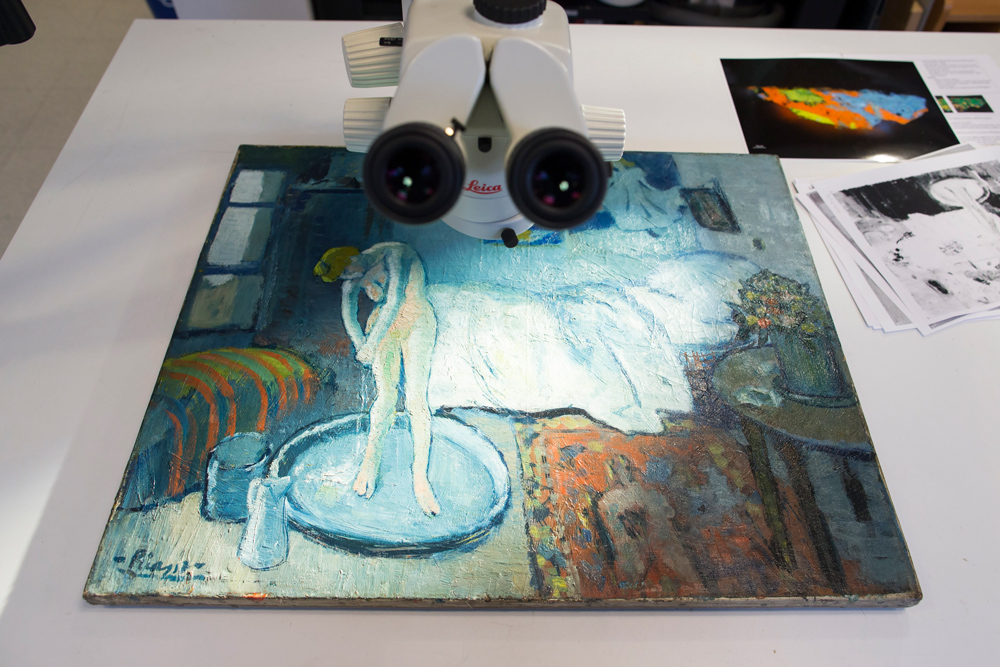

The Blue Room by Pablo Picasso

The Blue Room is regarded as one of Pablo Picasso's earliest masterpieces. It was painted when Picasso was 19 years old and living in Paris, and is one of the first works of his early "Blue Period" of melancholy scenes dominated by varying shades of blue.

In 2014, scientists announced that they had found a hidden image underneath the painted surface of "The Blue Room," showing the hidden portrait of a man wearing a bow tie, resting his chin on his hand, reported the Associated Press.

It's not yet known who the mystery man could be, but it's definitely not a portrait of Picasso himself. One possibility is the art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who hosted Picasso's first show in Paris in 1901.

Art historians say Picasso was poor but very productive at the time he painted "The Blue Room," so it wasn't unusual for him to reuse an earlier canvas for a new idea.

Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci

French scientist Pascal Cotte announced earlier this year that he'd found a hidden image of a different woman beneath the world's most famous portrait, Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa.

Cotte was able to examine the Mona Lisa at the Louvre Museum in Paris in 2004 under intense lights of different frequencies. He then spent more than 10 years analyzing the data from these experiments. Cotte said his research has revealed the original portrait on the Mona Lisa canvas, but it portrays a different woman who is looking off to the side instead of directly at the artist.

Da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa in around 1506. It's generally thought to portray Lisa Gherardini of Florence, the wife of a silk merchant.

But, Cotte thinks the original Mona Lisa shows a different Florentine woman of the time named Pacifica Brandano.

Not all art experts are convinced by Cotte's research, however. One art historian suggested his methods may have created an artificial image from the original brush stokes used by Leonardo to create the final portrait, but they did not represent a different portrait.

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci's famous portrayal of Jesus and his disciples at the Last Supper has been at the heart of some popular theories in recent years, as portrayed in the 2003 novel "The Da Vinci Code" by Dan Brown and the 2006 movie adaption of the book starring Tom Hanks.

But to art historians, da Vinci’s Last Supper is important for its expressive composition and use of perspective, which was something of an innovation at the time. Da Vinci aligned the figures and the walls of the painted room to strings radiating from a nail in the wall where the original is painted, above a dining hall in a monastery in Milan.

Da Vinci also created special tempura paints so that he could take his time over the wall-sized painting, instead of working quickly on wet plaster before it dried. When the abbot of the monastery complained that the painting was taking too long, the infuriated artist was said to have threatened to use the abbot's face as his model for the traitor Judas. In the end, da Vinci visited the prisons of Milan to find the perfect villainous face for Judas, who is seated fifth from the left.

Professional art historians say there is no evidence for the conspiracy theories about the Last Supper set out in "The Da Vinci Code," and other books that broach the topic; and they reject the identification of the figure to the left of Jesus as his female follower Mary Magdalene, instead of the apostle John.

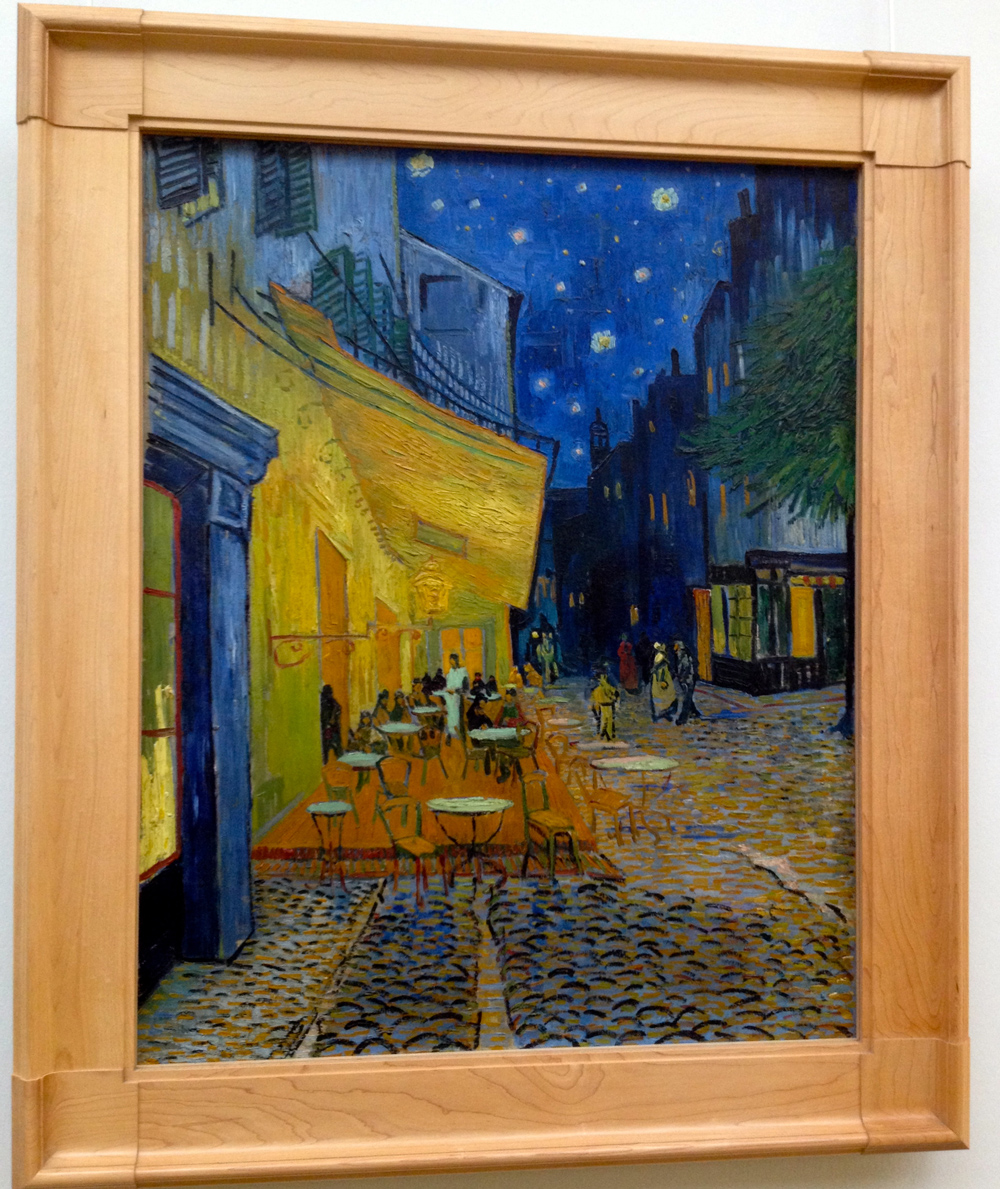

Café Terrace at Night by Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh's 1888 painting "Café Terrace at Night" is thought by some to include a representation of Leonardo da Vinci's "Last Supper."

The painting shows a lit cafe in the town of Arles in France, where the Dutch artist lived for a few years before his death in 1890.

The central figure in the cafe is a long-haired waiter wearing a white shirt and apron, surrounded by people seated at tables.

Independent researcher Jared Baxter argues that van Gogh was deeply religious before beginning his career as an artist, and Baxter thinks the painting is an example of an entire genre of "Last Supper" paintings by various artists that are modelled on da Vinci's original.

Baxter also notes the cross shape made by the frame of the window behind the waiter's back, the heavenly appearance of the well-lit cafe (compared to the dark streets outside) and the shadowy figure standing near the door who may represent the traitorous Judas.

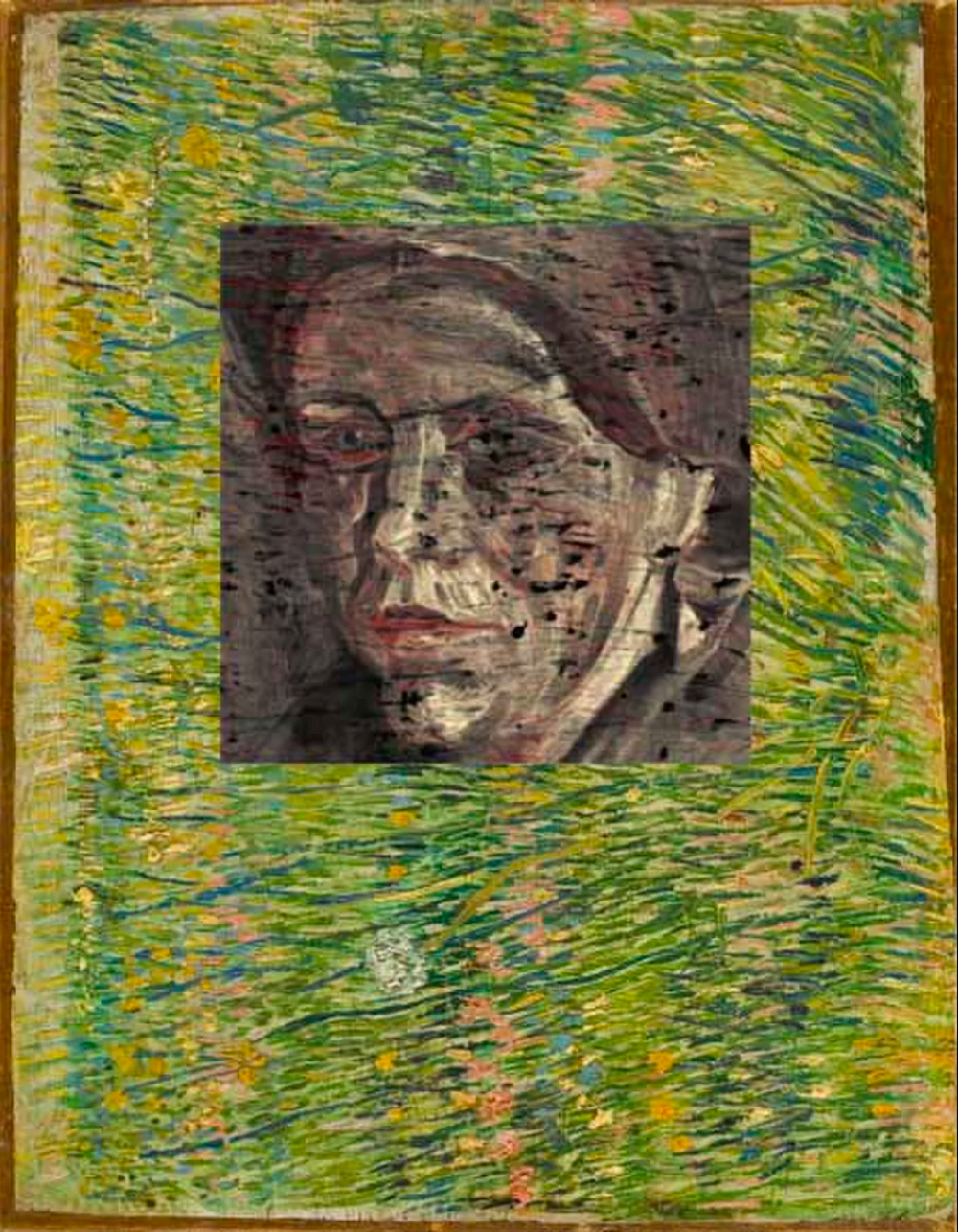

Patch of Grass by Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh was very poor for most of his life, and like many struggling painters, he often reused his old canvases. Up to 20 paintings at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, or around 15 percent of the artist's entire collection, are known to cover an earlier composition by the artist.

Research published in 2008 by scientists in the Netherlands and France revealed a previously unknown portrait by van Gogh, hidden beneath "Patch of Grass," which he painted in Paris in 1886 or 1887.

The researchers used powerful X-rays generated by a synchrotron accelerator to identify the chemical elements in the pigments of the hidden layers of paint, without affecting the paint on the surface.

Data from the X-ray scans were used to recreate a digital image of the hidden portrait of a Dutch farming woman, shown left, from Van Gogh's very early career as an artist.

The researchers think the hidden portrait was painted between 1884 and 1885, when van Gogh lived near the farming village of Nuenen and painted portraits of many of the local people. By the time he got to Paris, he may have thought the portrait of an old woman was "hopelessly out-fashioned," according to the researchers, and decided to paint over it with a colorful Parisian-style floral scene.

Self Portraits by Rembrandt van Rijn

Did the Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn do his best work with mirrors?

In 2001, British artist David Hockney and American physicist Charles Falco announced that they had found indications that Rembrandt and other Old Masters relied heavily on the use of lenses and curved mirrors to create their life-like scenes and portraits.

And in August 2016, two researchers in the United Kingdom, artist Francis O'Neil and physicist Sofia Palazzo Corner, published a study in the Journal of Optics that explained how Rembrandt could have used combinations of curved mirrors and lenses to create his celebrated self portraits.

The researchers see many details in Rembrandt's self-portraits that support their theory, including the strong light in the center of the portraits and the relative darkness at the edges, which is also seen in reflections projected by curved mirrors. [Read more about the mirrors and optical tricks that Rembrandt may have employed]

The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein

"The Ambassadors" is a painting by Hans Holbein, a celebrated German portrait artist who lived in Tudor England for much of his life.

In addition to the two gentleman referred to in its modern title, the painting features many curious details that have stimulated great debate, including several carefully detailed scientific instruments, one of the earliest known representations of a globe of the world, and the extraordinary depiction of a human skull rendered in an extreme perspective at the base of the main image.

The anamorphic skull's proportions are distorted so that it can only be seen in normal perspective from an especially sharp angle, or by using a mirror positioned against the image. Some art historians think the painting may have been intended to stand beside a staircase, so the skull would be visible to people walking up the stairs.

There is much debate about why Holbein chose to include the skull and its unusual, out-of-place perspective. The motif of a human skull is common in Renaissance paintings known as "vanitas" or "memento mori," as a reminder of the impermanence of human lives and earthly glories.

The many scientific and navigational instruments in the painting include a wonderfully detailed globe of the Earth, showing the outlines of Europe, Africa and the New World; a celestial globe; a polyhedral sundial; an astrolabe; a quadrant; and a torqetum, an instrument designed to measure the angles between three points in the sky.

Analysis of the settings on the instruments suggests to some researchers that they refer to Good Friday, the formal date of the crucifixion in the Christian calendar — a further cryptic clue to the symbolic meanings of the painting.

Lost Portrait by Edgar Degas

Like his contemporary Vincent van Gogh, the French artist Edgar Degas often reused his painted canvases when money was tight or when the earlier work had lost its appeal.

In 2016, researchers in Australia announced that they had reconstructed a previously unseen portrait by Degas from the layers of paint beneath a later portrait that now hangs in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne.

The later portrait has long been known to cover an earlier work by Degas, and the lines of the original have become more apparent as the painting has aged.

By conducting X-ray fluorescence and absorption experiments on the painting at the Australian Synchrotron facility in Melbourne, the researchers were able to recreate the hidden image, and to identify the subject as Emma Dobigny, an artist's model who sat for Degas and other painters in the 1870s. [Read more about the hidden portrait by Degas]

Sistine Chapel ceiling by Michelangelo

The famous frescoes painted by Michelangelo on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome include a celebrated image of God creating Adam, the first man.

One of the carefully rendered details of the scene is the cloud or billowing cloak that surrounds the figure of God and a host of angels, which resembles the shape of a human brain.

Yes, seriously: Research published in 2010 by two neuroanatomists at Johns Hopkins Medical School highlighted the many similarities between the brain-shaped cloud and human brains, including painted features that appear to represent the cerebellum, the optic nerve, the pituitary gland and the vertebral artery.

The researchers noted that Michelangelo had studied human anatomy and even dissected dead bodies to learn details that would give realism to his paintings, so he would have been familiar with the shape of the brain and its major anatomical features.

The scientists think Michelangelo purposely painted a brain-shaped cloud or cloak to show that God was not only endowing Adam with life, but also with reason and intelligence.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.