Aaron Hernandez's CTE: 5 Facts About This Brain Disease

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

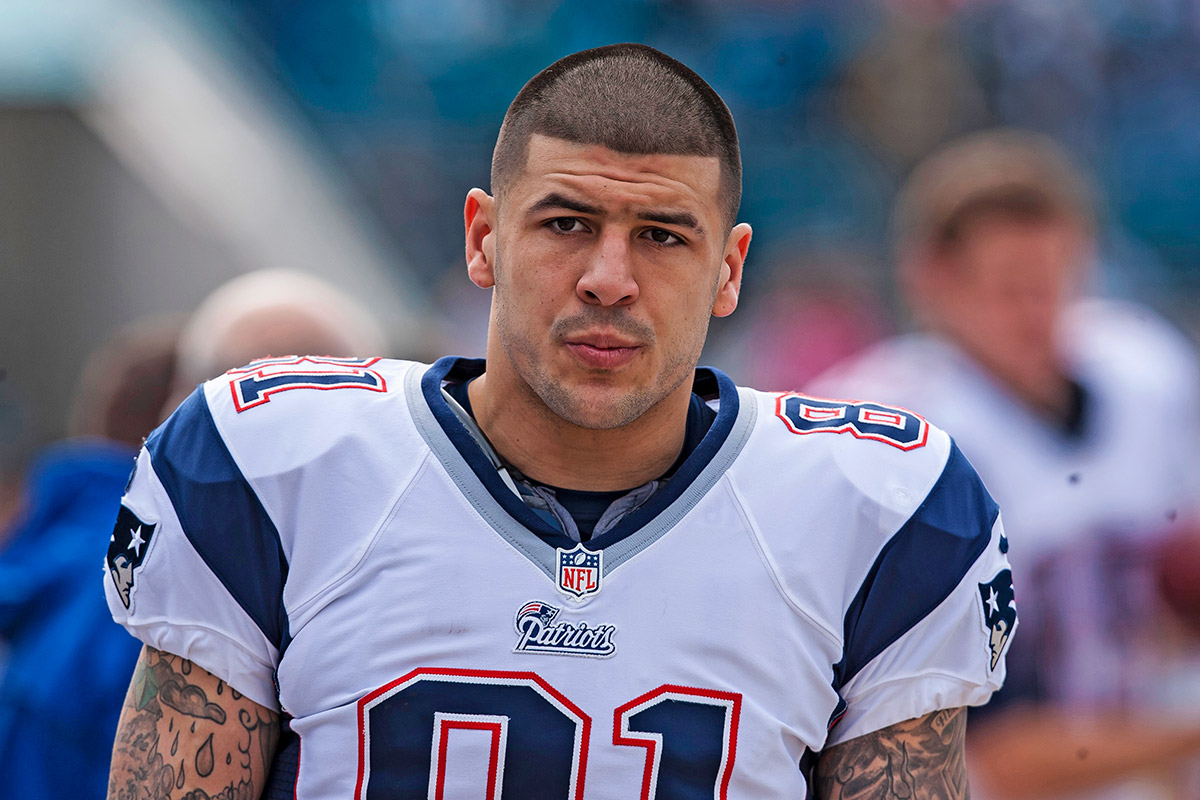

An autopsy of former NFL player Aaron Hernandez's brain revealed that the athlete had a severe form of the brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) when he died in April. CTE is a degenerative brain condition that has been found in the brains of professional football players and boxers, according to news reports.

The analysis of Hernandez's brain was particularly striking; in a press release, his family's lawyer announced that Hernandez had "the most severe case they had ever seen in someone of Aaron's age." (Hernandez was 27 when he committed suicide while serving a life sentence in prison for murder.) In fact, Hernandez's CTE had progressed to the level that doctors might expect to see in a 60-year-old, according to the The New York Times.

But CTE is often shrouded in mystery and speculation. Here are five things to know about the condition.

CTE can be diagnosed only after death.

To diagnosis CTE, doctors must examine the brain during an autopsy to measure the type and severity of damage to the deceased person's brain cells, according to the Alzheimer's Association.

"There is research looking into ways to diagnose [CTE] with special types of imaging studies," said Dr. Erin Manning, a neurologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City. "But nothing has been confirmed at this time. If it can be diagnosed before death, then likely strides can be made in determining" what type of symptoms accompany the disorder, she added.

Some types of brain scans along with thorough analysis can be used to rule out other causes for someone's dementia symptoms, but that's not the same as making a definitive diagnosis of CTE, the Alzheimer's Association says.

CTE is not the same as a concussion.

Because it's so difficult to study CTE, researchers don't yet know what causes it. Although there's a link between CTE and frequent blows to the head, that link isn't as clear-cut as it is with a concussion.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Concussion is a reversible brain injury that happens after a head injury," Manning told Live Science. "CTE is a neurodegenerative disease, like Alzheimer's dementia, that we do not yet know the cause for."

Concussions are a type of traumatic brain injury that is caused when the brain forcefully bounces against the skull, according to the Mayo Clinic. Usually, the cerebrospinal fluid in a person's skull cushions the brain from crashing into the skull, but a strong blow to the head or violent shaking can cause the brain to hit the skull, resulting in an acute injury, the Mayo Clinic says.

CTE, however, is totally different. Instead of a single injury, it's a degenerative neurological condition, meaning that it gets worse over time, Manning said. The only common threads in these cases are that they involve brain damage and are commonly seen in contact sports like boxing and U.S. football.

CTE has a wide range of symptoms.

People with CTE can have a wide range of emotional, cognitive and physical symptoms, depending on what parts of their brains are affected and the extent to which the CTE has developed, according to a 2012 study published in the journal Brain Imaging and Behavior.

CTE can cause the cognitive impairments, memory loss and depression associated with other forms of dementia, according to the Mayo Clinic. People with CTE can also become more aggressive, impulsive or prone to substance abuse. In addition, the condition has been linked symptoms including difficulty with balance and swallowing, as well as suicidal behavior. (The number for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255.)

But because CTE isn't diagnosed until after death, it can be difficult to directly connect certain symptoms to the condition. Generally, doing so involves taking note of behavioral or cognitive changes in people and, later, connecting the dots once CTE has been confirmed.

Manning said that she hopes continued study of CTE will lead to better prevention, diagnosis of symptoms and perhaps even treatment. "At this point, there is more that we don't know than we [do] know," she said.

There are different stages of CTE with different symptoms.

Hernandez was found to have Stage 3 CTE, out of four stages. These stages of the disease were first described in 2012 in the journal Brain.

The first and least-severe stage of CTE is associated with headaches and some difficulty concentrating more than anything else, according to the Brain study. It's not until the second stage of the disease that people struggle with managing their emotions. At this point, people may have mood swings, depression, short-term memory loss and some problems with language.

In Stage 3 and 4 CTE, the emotional, cognitive and memory symptoms that emerge in Stage 2 worsen. In Stage 4, people can experience dementia symptoms that might be confused for those stemming from Alzheimer's disease or Parkinson's disease, according to the Brain study.

CTE is linked to more than just football.

Although CTE cases in former NFL players garner a lot of media attention, other types of athletes can also develop the condition.

The association with football comes in part because of a skew in demographics, Manning said.

"The problem with talking about how common it is, is that the vast majority of brains that have been studied are in athletes who they or their family believed that there was a problem," she said.

In fact, the first described cases of CTE came from boxers who were repeatedly punched in the head for years on end, Manning said, but now that attention has shifted to football players.

And the sport that led to the most head-injury-related emergency room visits in 2009 was cycling, with more than 85,000 visits, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Football came in second, with more than 46,000 ER visits, but was closely followed by baseball and softball, basketball, and water sports. There were even around 10,000 visits due to golfing accidents.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus