Eat, Pray, Fossilize? Praying Mantis Fossil Is 110 Million Years Old

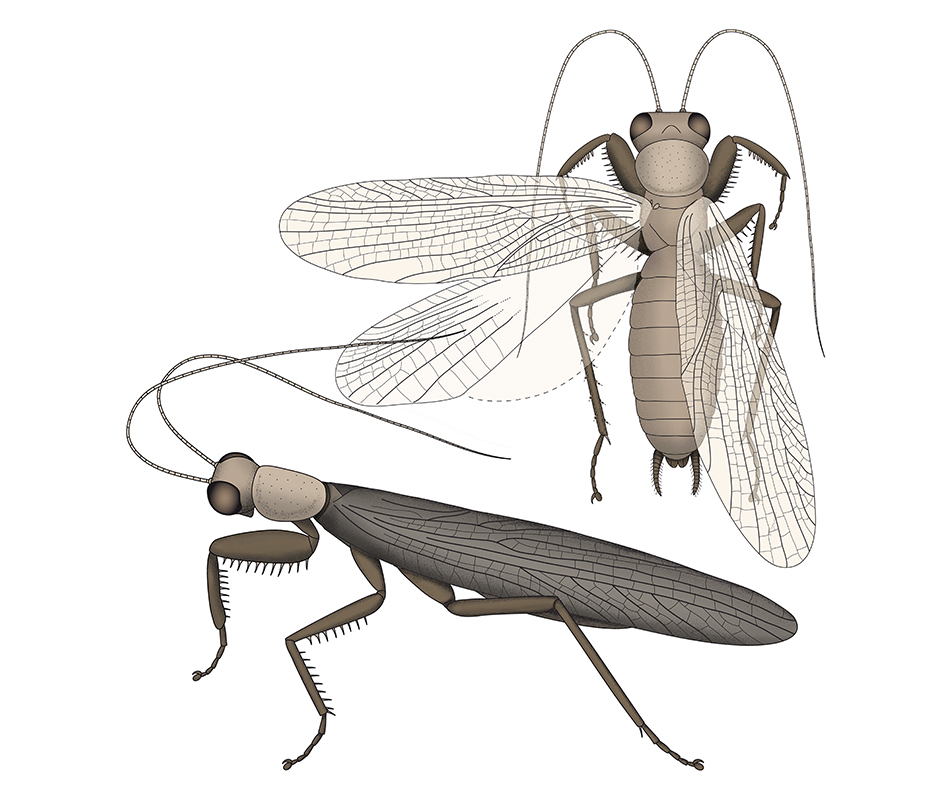

Praying mantises are known for their specialized "arms" — a pair of oversized appendages near the top of the thorax that are lined with sharp spines and capable of immobilizing prey. And a recently discovered fossil sheds light on how those lethal weapons may have emerged.

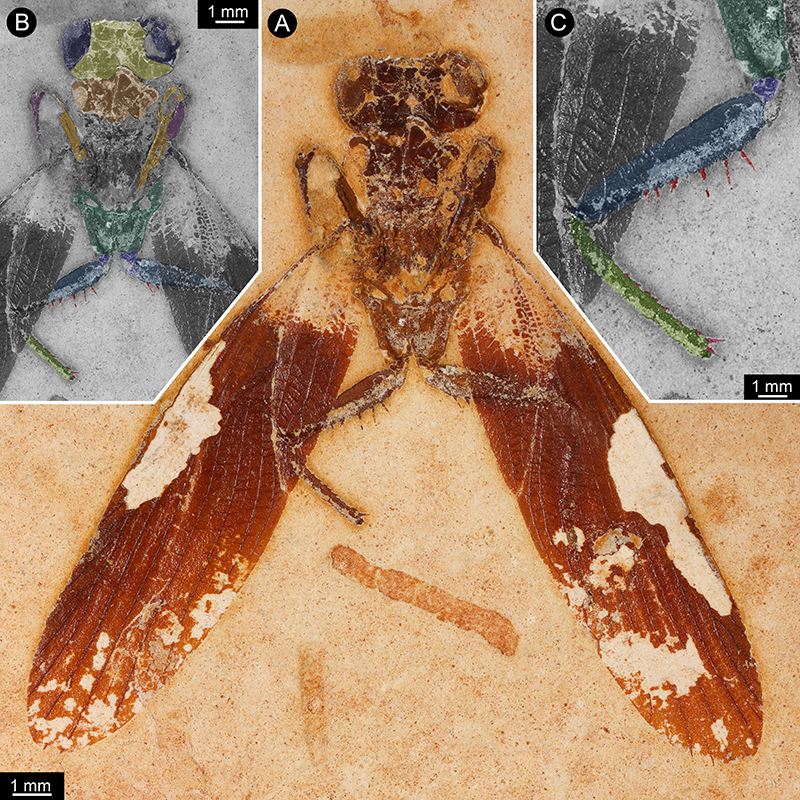

Scientists described an exceptionally well-preserved praying mantis fossil embedded in a rock slab excavated from a site in northeastern Brazil, dating the mantis to about 110 million years ago and identifying it as Santanmantis axelrodi, according to a new study.

While the earliest mantids — another name for insects in the mantis family — can be traced to the Jurassic Period (199.6 to 145.5 million years ago), the Cretaceous Period (145.5 to 65.5 million years ago) is when the group's diversity began to emerge, the study authors wrote. This fossil is more complete than any other specimen of this species, revealing previously unknown details of the body parts in early mantids that are adapted for predation. [Lunch on the Wing: Mantises Snack on Birds (Photos)]

The fragile remnants of ancient insects are far rarer than fossils of more robust creatures with shells or skeletons, yet a number of fascinating insect specimens have stood the test of time. The oldest example of insect sex dates to 165 million years ago; the oldest known stick insect dates to 126 million years ago; and a 46-million-year-old mosquito was preserved while still engorged with its final blood meal.

In the newly described fossil mantis, much of the insect's head, thorax and wings were preserved. The head measured about 0.2 inches (4 millimeters) wide, while the wings measured 0.6 inches (16 mm) long and retained remarkably detailed vein patterns, the study authors wrote.

Two pairs of legs were also present in the fossil, with the uppermost pair folded up under the head so that little of their structure was visible. But the lower legs were extended, revealing spines on both the upper and lower parts — something that was not apparent in other fossils of this species, the researchers explained.

The longest spines measured about 0.02 inches (0.4 mm) in length, standing erect and angling out from the leg at about 90 degrees from a slightly wider base — which meant that they were probably rigid — and they had what appeared to be a sharp tip, the scientists wrote in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This marks a significant difference from the predatory adaptations of modern mantids, which typically bear spines only on their primary limbs, the scientists explained. The sturdy, erect spikes on the fossil's secondary pair of limbs "strongly indicate that these appendages were involved in the prey-catching process," the scientists wrote, suggesting that predatory behavior in these ancient insects may have been more diverse than expected — certainly more so than in their descendants alive today.

The findings were published online July 24 in the open-access journal PeerJ.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus