Can You Put a Price on the Great Barrier Reef? Economists Just Did

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Its biodiversity may be priceless, but the Great Barrier Reef has a real economic value — 56 billion Australian dollars ($42.5 billion) of real economic value, to be precise, a new report finds.

The report, published by the financial consultancy Deloitte Access Economics, also found that the enormous coral reef off of Queensland, Australia, supports 64,000 jobs in that country and contributed AU$6.4 billion ($4.9 billion) to Australia's economy in the 2015 to 2016 fiscal year. But the reef is under threat from climate change, with back-to-back bleaching episodes threatening the survival of vast swaths of coral.

"This report sends a clear message that the Great Barrier Reef — as an ecosystem, as an economic driver, as a global treasure — is too big to fail," Steve Sargent, the director of the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, said in a statement. [Image Gallery: Great Barrier Reef Through Time]

Economic boon

The Great Barrier Reef Foundation commissioned the report, which drew from publicly available economic data as well as surveys of Australian residents. The analysis counted direct economic benefits, such as income made by tour-dive companies or commercial fishing supported by the reef. If also included indirect economic benefits, like the boon to restaurants and hotels near the Queensland coast and the economic value of the research being done on the Great Barrier Reef.

Ninety percent of the AU$6.4 billion the reef brought into Australia between 2015 and 2016 came from direct tourism activities. [Images: Colorful Corals of the Deep Barrier Reef]

Iconic value

Beyond the direct and indirect benefits to Australia's economy, the reef also provides what Deloitte Access economists called "indirect" or "non-use" value. This is the value the Great Barrier Reef has by simply existing: its social value, its importance for biodiversity and its importance as a point of Australian identity and pride.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers used a survey of 1,000 Australians and 500 non-nationals to try to estimate this indirect value. They found that 54 percent of Australians and 63 percent of international respondents said they'd be willing to pay to protect the Great Barrier Reef. Of those people, most said they were motivated by protecting the reef for future generations (70 percent of Australians) or because the reef is "important to the planet" (62 percent of international respondents). Of those who said they wouldn't be willing to be levied to protect the Great Barrier Reef, most said they couldn't afford such a tax, and others said the funding should come from another source. Only 2 to 3 percent said they did not think the Great Barrier Reef was important or under threat.

The AU$56 billion ($42.5 billion) valuation comes from extrapolating the direct and indirect economic benefits of the reef over the next 33 years, until 2050. Over that time period, the direct-use benefit from tourism is AU$29 billion ($22 billion). Other contributors to that number include ecosystem services, like the ecological functions the reef conducts to cycle nutrients and protect the coastline, and the "brand value" of the reef in raising Australia's reputation as an international destination.

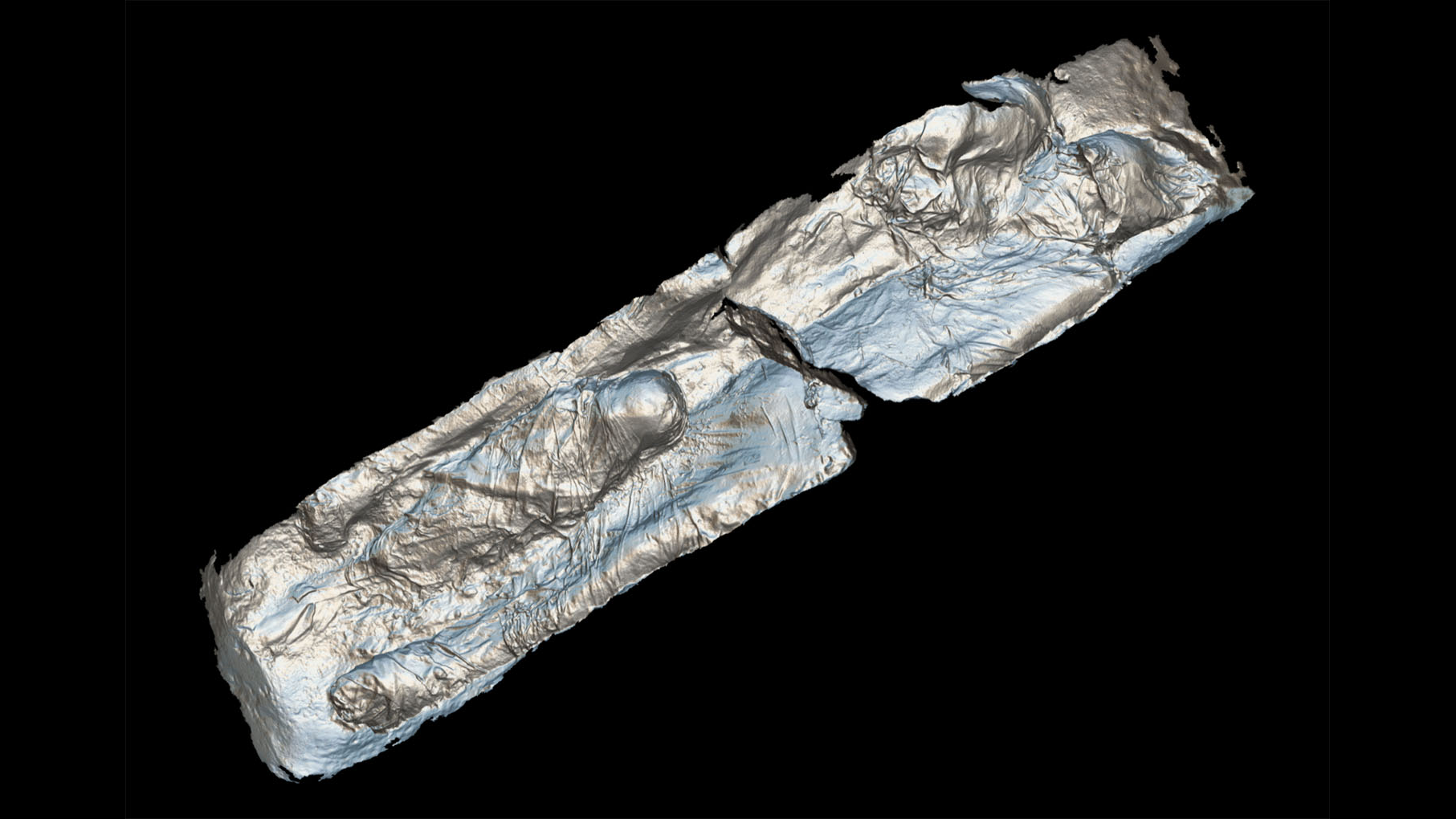

The reef also has value that can't be estimated in dollars, the economists concluded. It's an important place for indigenous Australian cultural and religious heritage, and archaeological sites along the reef have revealed artifacts, such as stone tools and rock art, that hint at the earliest occupants of Australia.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus