Asteroid Collision May Have Tipped Saturn's Moon Enceladus

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Enceladus, an icy moon of Saturn that could host life, may have tipped over long ago.

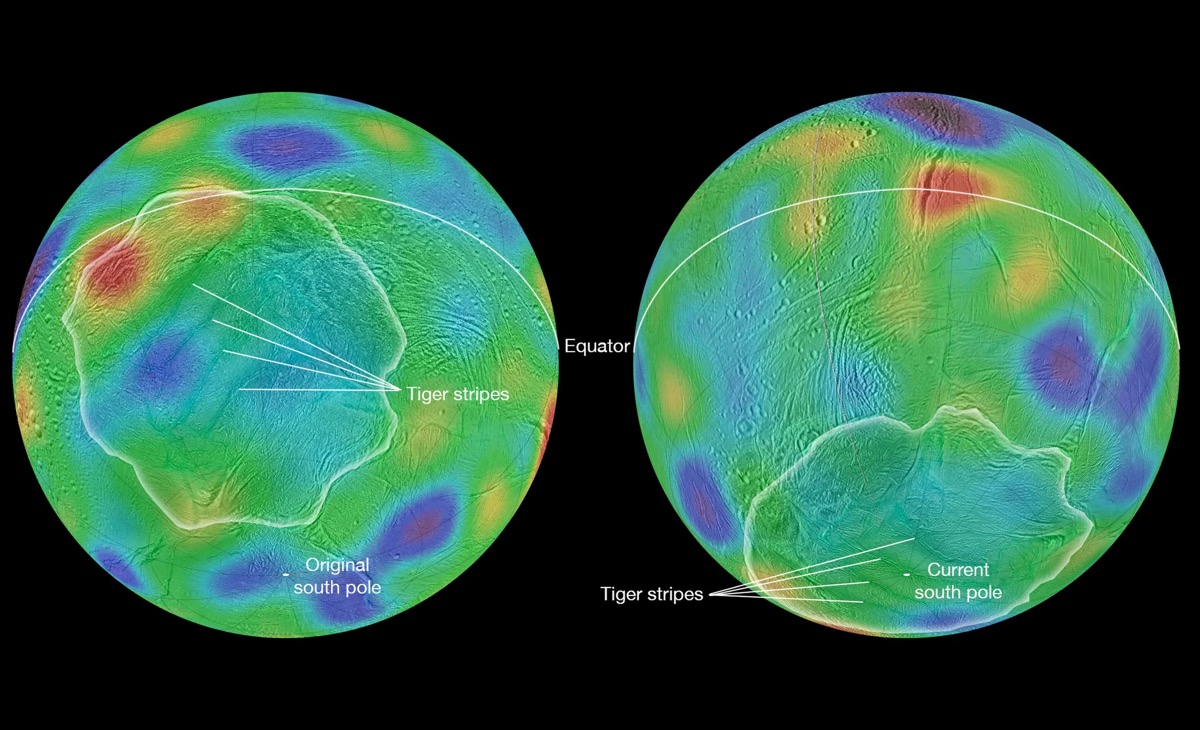

NASA's Cassini orbiter, which has been studying Saturn and its many moons up close since the probe arrived in 2004, has found evidence that Enceladus' axis of rotation has rotated by 55 degrees. That would mean the moon moved more than halfway onto its side.

A collision with an asteroid or some other object in deep space may have caused the moon's tilt, NASA officials said in a statement. [Photos: Enceladus, Saturn's Cold, Bright Moon]

"We found a chain of low areas, or basins, that trace a belt across the moon's surface that we believe are the fossil remnants of an earlier, previous equator and poles," Radwan Tajeddine, a Cassini imaging team associate at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, who led the new study, said in the statement.

Tajeddine and his team of researchers suspect that the impact occurred near Enceladus' south pole, he said. There, the icy moon's surface consists of strange-looking, geologically active terrain of a type that scientists call "tiger stripes."

The long, linear fractures seen on Enceladus' south pole differ from the texture around the moon's north polar region, where tons craters and fissures point to an old surface unchanged by geological activity.

"The geological activity in this terrain is unlikely to have been initiated by internal processes," Tajeddine said. "We think that in order to drive such a large reorientation of the moon, it's possible that an impact was behind the formation of this anomalous terrain."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shortly after Cassini arrived at Saturn, the spacecraft discovered mysterious plumes of water spewing into space from the tiger stripes in the icy moon's surface, hinting at the existence of a subsurface ocean.

Whether the tiger-stripe terrain was created by an impact or some other geological process, Tajeddine and colleagues think it likely "caused some of Enceladus' mass to be redistributed, making the moon's rotation unsteady and wobbly," NASA officials said in the statement.

"The rotation would have eventually stabilized, likely taking more than a million years. By the time the rotation settled down, the north-south axis would have reoriented to pass through different points on the surface — a mechanism researchers call 'true polar wander,'" the statement said.

This would explain why the north and south polar regions are so vastly different in texture and geological activity, the researchers suggested. It's possible that the two poles looked the same before something came by and bumped into the little moon, the scientists said.

The results of the study by Tajeddine and colleagues were published online in the journal Icarus on April 30.

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is an editor at Liv Science's sister site Space.com with 10 years of experience in science journalism. She has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus