Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The first fleet of robotic spacecraft that humanity launches to explore exoplanets may include a few kamikazes.

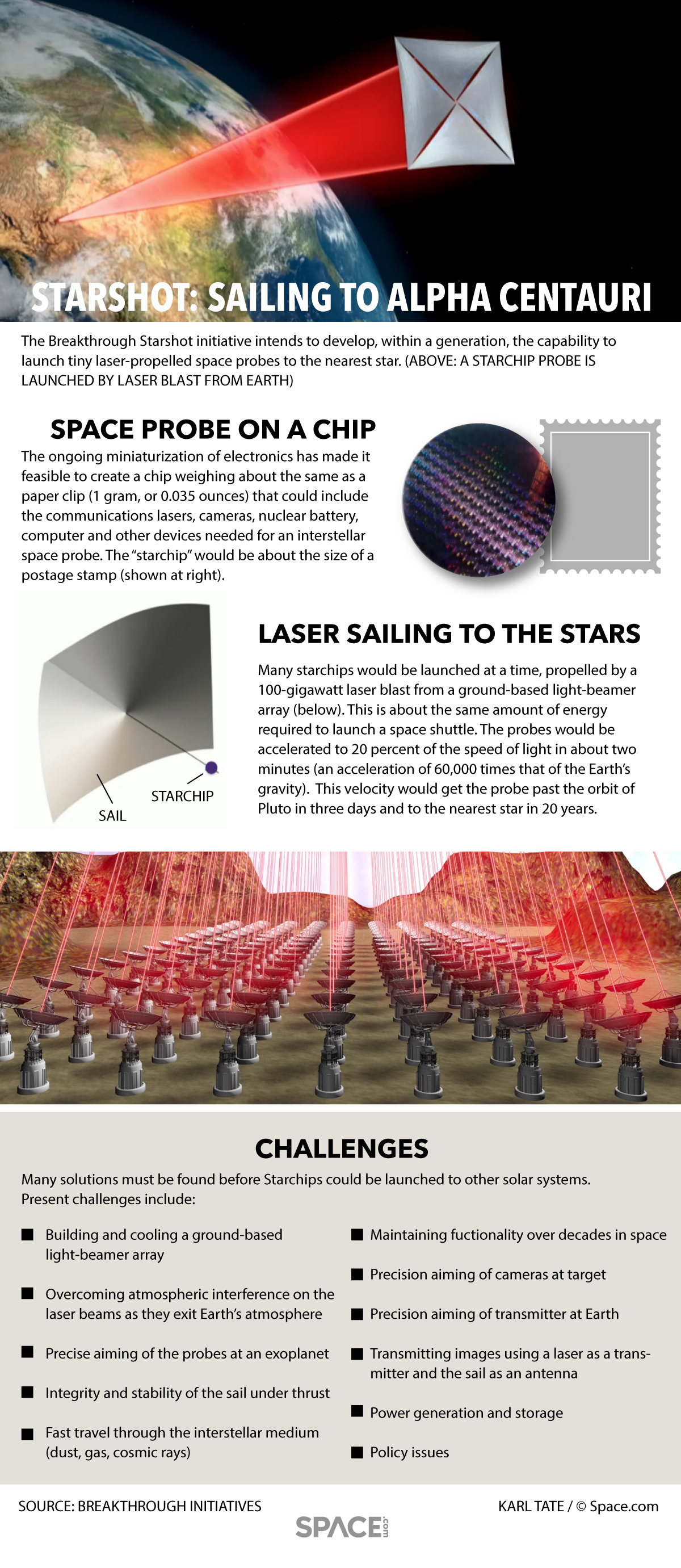

The $100 million Breakthrough Starshot initiative is working to develop an interstellar spaceflight system that would use powerful lasers to accelerate tiny, sail-equipped probes to 20 percent the speed of light.

The baseline plan calls for the robotic nanocraft to hunt for signs of life and gather other data during flybys of nearby alien worlds such as Proxima b, a potentially habitable planet located just 4.2 light-years from Earth. But the scientific return would be even greater if some of the 1-gram probes actually slammed into their target worlds, some researchers said. [Breakthrough Starshot in Pictures: Laser-Sailing Nanocraft to Study Alien Planets]

"I want 10 — at least 10 ships, not just one," Harvard University astronomy professor Dimitar Sasselov said April 20 during a panel discussion at the annual Breakthrough Discuss conference at Stanford University.

"So then, two of them I'll point at the planet, straight into the planet, hit the planet and create a thermal event in the atmosphere," added Sasselov, who's also the founding director of the Harvard Origins of Life Initiative. The other eight probes would "beam the data back, because you'll get a lot better characterization of what's in the atmosphere," he said.

(Sending 10 probes shouldn't be a problem; each spacecraft will be relatively cheap to manufacture, Breakthrough Starshot team members have said, and the project aims to launch many of the spacecraft toward each target body.)

This suicide strategy was also raised as a possibility by Philip Lubin, a physics professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who's the driving force behind Breakthrough Starshot's planned laser-propulsion system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Maybe you have a small mothership that sends out little daughters [and] drops them in the atmosphere," Lubin said during a separate presentation at Breakthrough Discuss on April 20. "And then perhaps you could telemeter data back from the daughters to the mother saying, 'I'm sacrificing myself for the good of science and humanity back home.' You could possibly do spectroscopy from the impact on the atmosphere and the surface, and there are ways to measure gravity."

Spectroscopy is a technique in which astronomers study the wavelengths of light coming from a planet to figure out what's in that world's atmosphere. If gases produced by life are present, spectroscopic observations could potentially spot them. (Because "biosignature" gases can generally also be created by abiotic processes, a compelling case for alien life would probably require the detection of more than one, researchers have said. For example, the presence of both methane and oxygen in a planet's atmosphere would make a strong case, since these two gases can't coexist for long.)

The data-generating "thermal event" referenced by Sasselov would be pretty dramatic. A Starshot probe traveling at relativistic speeds would release about as much energy as 1 kiloton of TNT when it detonated in the atmosphere, Lubin said.

University of Hawaii physicist Jeff Kuhn said the explosion would be even more powerful; during a different Breakthrough Discuss panel on April 21, he estimated the yield at perhaps 100 kilotons. For comparison, the atomic bomb that the United States dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima toward the end of World War II had an explosive yield of about 15 kilotons.

One of the biggest challenges facing the Breakthrough Starshot program is ensuring that the tiny probes can relay their images and other data back to their handlers here on Earth, team members have said. If the project cannot solve that problem, suicide dives could at least provide confirmation that an interstellar mission reached its target, Kuhn said.

"If we could string out a bunch of these … maybe we could set it up so that, with all of our ground-based telescopes, we could get the self-destructive signal that said, 'Yeah, we made it,'" he said. "It might start interstellar warfare, but it would satisfy that."

As that last remark suggests, the kamikaze strategy would likely be controversial and provoke spirited debate, especially considering that Starshot aims to prioritize the study of worlds that may be capable of supporting life. (Indeed, Sasselov's comments were greeted with nervous chuckles by some of his fellow panelists at the Breakthrough Discuss conference, one of whom said, "I'm picturing 'Independence Day.'")

But the Starshot team and the world at large have some time to chew over such ethical issues. The first interstellar nanoprobes probably won't launch for another 20 years or so, even if the team makes good progress and everything goes well, Starshot team members have said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus