'Artificial Womb' Keeps Extremely Premature Lambs Alive for Weeks

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An experimental "artificial womb" recently kept extremely premature lambs alive for weeks, suggesting that such a device could one day help save the lives of very premature human babies, a new study finds.

The new machine supported the lambs for up to 28 days, which is the longest amount of time that an artificial womb has kept animals stable, the researchers said.

"We tried to develop a system that as closely as possible reproduced the environment of the womb, replacing the function of the placenta," said study senior author Dr. Alan Flake, a fetal surgeon and director of the Center for Fetal Research in the Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. "This, in theory, should allow support of premature infants for a period of weeks, and thereby reduce dramatically their mortality and morbidity rates and improve their outcomes in both the short and long terms." [7 Baby Myths Debunked]

The scientists experimented with eight extremely premature lambs that had been carried by their mothers for only 100 to 115 days; a normal pregnancy in sheep lasts 152 days. The lambs weighed 3.3 to 5.3 lbs. (1.5 to 2.4 kilograms) when they were placed in the device; when they exited, they were about 5.7 to 9.9 lbs. (2.6 to 4.5 kg). In terms of their lung development, these lambs were equivalent to human infants at 22 to 24 weeks of pregnancy, the researchers said.

About 30,000 babies are born "extremely premature" in the U.S. each year — that is, before 26 weeks of pregnancy, the researchers said. Extreme prematurity is the leading cause of infant mortality in the United States, accounting for one-third of all infant deaths, they added. The total annual medical costs of prematurity in the United States reach an estimated $43 billion, they said.

Advances in medicine can now save extremely premature infants born at 22 to 23 weeks of pregnancy, who may weigh less than 1.3 lbs. (600 grams). Still, at that age, "death rates are as high as 90 percent," Flake told Live Science. The babies who survive have as high as a 70 to 90 percent risk of life-impacting morbidities or sicknesses, such as chronic lung disease and other complications of organ immaturity, he said.

The aim of the new device is to support the growth and development of these extremely premature infants for only a few weeks. Once they reach 28 weeks old, "you remove most of the risks of prematurity," Flake said. "The outcomes are very good."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One previous artificial womb could keep fetal goats alive up to about 22 days, but these animals required dialysis, had muscles so weak that they were immobilized, and ultimately succumbed to respiratory failure. In contrast, the new artificial womb could keep premature lambs alive for as long as 28 days, and they remained healthy, the study authors said. [11 Facts Every Parent Should Know About Their Baby's Brain]

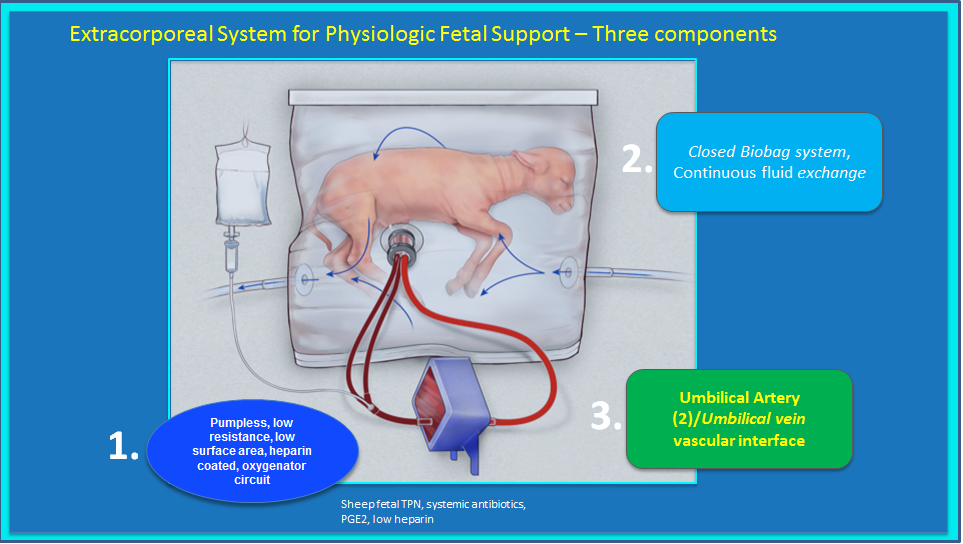

The new device evolved over three years through a series of four prototypes. One of the key features of the machine is that the premature lambs within it did not breathe in air. Instead, they were suspended in a plastic bag of liquid mimicking amniotic fluid, which surrounds fetuses in the womb. "Fetuses normally breathe fluid, which helps in lung development," Flake said.

Incidentally, natural amniotic fluid "is predominantly fetal urine," Flake said. "The fetus swallows amniotic fluid and then urinates to form amniotic fluid. It's hard to believe we all start out that way."

Another key feature of the new device is that there is no external pump to drive the circulation of blood in the device, because pressure even from gentle pumps can fatally overload an underdeveloped heart, the researchers said. Instead, the heart of each lamb pumped blood through its umbilical cord into a machine outside the bag that substituted for its mother's placenta, helping supply the lamb's blood with oxygen and nutrients while also removing carbon dioxide.

The lambs grew in a sealed environment insulated from variations in temperature, pressure and light, and protected from pathogens that could cause hazardous infections. Electronic monitors kept track of their vital signs.

After the scientists removed the lambs from the device, they found that the animals' lungs functioned very well, and were very similar to ones from normal lambs of the same ages, Flake said. Their brains, livers and other organs also seemed to function normally, and the lambs grew wool, opened their eyes, became more active, and appeared to have normal breathing and swallowing movements.

Although the scientists euthanized many of the lambs in their experiments to examine their biology, one survivor is now about 4 months old, and another is more than a year old; they were retired to a farm in Pennsylvania, the researchers said.

"They're reasonably normal in every respect we can tell," Flake said. "We do have plans for long-term observations of survivors, to look for some hidden morbidity. The problem that arises with that, though, is that it's hard to get a handle on things such as mental capacity or behavioral abnormalities in lambs, so it's a problem making comparisons with humans."

The researchers plan to do more animal studies with advanced versions of the device "in the next two to three years, and then the first human trials within three to five years," Flake said. "And honestly, those are conservative estimates."

Human trials

One major change the researchers said they need to make to their device for human trials is to downsize it, because extremelypremature human infants are about one-third the size of the lambs used in the study. In addition, the researchers are investigating what molecules they might add to their artificial amniotic fluid so that it more closely mimics the real thing, study co-lead author Marcus Davey, also of Children's Hospital of Philadelphia in a conference with reporters.

Flake cautioned that not every extremely premature baby can benefit from this device. "One limitation is that they need to be delivered by cesarean," from their mothers, before doctors can put them into the artificial womb, Flake said. "I would anticipate that maybe 50 percent or so of extremely premature infants can be put on the system," he said.

Once infants are placed in the devices, they will likely be kept in covered incubators that doctors can keep an eye on with cameras and that can play sounds from their mothers, he said. "We'd try to make the environment parent-friendly," Flake said.

The researchers stressed that they do not aim to support fetuses that are more premature than 23 weeks. The extremely tiny sizes of such young fetuses make it difficult for the scientists to provide vital blood flow and ventilation, Flake said.

"There's a lot of sensationalistic conversations about supporting humans artificially from the embryo onward," Flake said. "The reality is that there is not present technology, nor even one on the horizon, that can support an embryo in a test tube."

The scientists detailed their findings online today (April 25) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus