Get a Grip: Hairy-Footed Bedbugs Foil Slick Traps

If you thought bedbug-proofing your bed with hard-to-climb traps would protect you from pesky biting insects, you might have to rethink that. Cup-like traps that fit over a bedframe's legs have a slick inner surface that usually defeats tiny climbers. But when it comes to these traps, bloodsuckers from one bedbug species have a distinctly "hairy" advantage over their cousins, according to a new study.

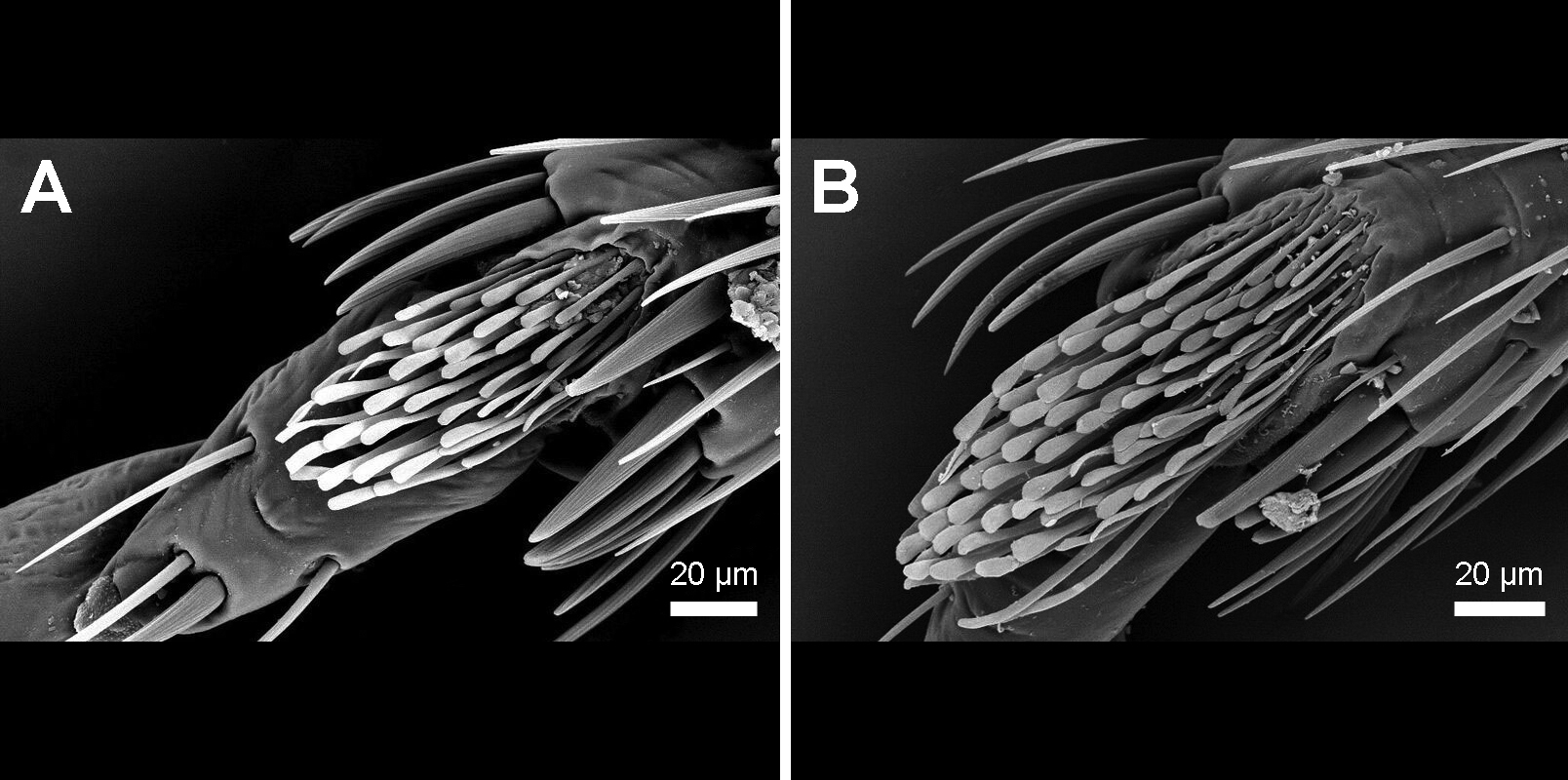

Observed with the naked eye, bedbugs of the species Cimex hemipterus appear nearly identical to the species Cimex lectularius. But magnify their legs under a microscope, and a difference emerges. In both species, the bedbugs' feet are lined with an abundance of tiny hairs. Those hairs are denser in C. hemipterus, making it a better climber on slick surfaces, researchers explained in the study.

Adult C. hemipterus bugs handily escaped all of the bedbug traps that were tested in the study, while most adult C. lectularius individuals weren't so lucky. When larvae of both species were tasked with climbing out of the traps, however, most of the youngsters from both species were left slipping and sliding, the scientists reported. [Bedbugs: The Life of a Minimonster (Infographic)]

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded",function(){BZ.init({animationType:"filmstrip",contId:"bzWidget",catId:10654,keywordId:"",flowId:2278,pubId:36757});});

C. lectularius, the common bedbug, is typically found in regions that are temperate and subtropical, while escape artist C. hemipterus, the tropical bedbug, is native to tropical and subtropical zones. However, both species coexist in some parts of Taiwan, Australia, Africa and Florida.

Bedbug traps developed in the United States are tested on the common bedbug, which is more widespread across the U.S. But while those snares are used for protection against bedbugs worldwide, the study authors questioned whether traps for common bedbugs are, in fact, equally effective against tropical bedbugs.

Climbing the walls

The researchers compared the escape success of both species using four brands of pitfall traps, which have smooth inner surfaces to trap bedbugs and prevent them from reaching a sleeper. They measured the vertical friction forces for each trap, then tested them with male and female adult bedbugs, as well as with larvae in the fourth to fifth instar — stage of development — to see if they could scale the traps' slippery walls.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most of the common bedbugs were contained by the traps, but tropical bedbugs of all development stages were able to escape from the four traps. In fact, one of the traps failed to contain any adult tropical bedbugs at all.

Bedbugs are known to use specialized claws to climb on rough surfaces, while they use leg parts called tibial pads — with the help of hollow filaments called tenent hairs — to climb smooth surfaces, the study authors wrote. They suspected that there was something unique about tropical bedbugs' feet and hairs that made them better at climbing out of the traps.

The scientists euthanized the insects and coated them with gold to better visualize the tibial pads under a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Scrutinizing SEM images from different angles allowed researchers to count individual hairs on the bedbugs' feet.

They found that common bedbugs had an average of 216 tenent hairs on their tibial pads, while tropical bedbugs had an average of 347 hairs. The extra hairs on these leg parts likely help the bugs get more of a grip, though it's not clear exactly how they work. Perhaps a type of fluid released by glands in the feet is pumped into the hollow hairs to help with climbing, but more tests would be required to know for sure, the study authors noted.

The findings were published online today (March 15) in the Journal of Economic Entomology.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.