Wind, Rain, Heat: Health Risks Grow with Extreme Weather

ATLANTA — As climate change proceeds, there will be more extreme weather events, and these events pose a threat to people's health, experts say.

The annual number of natural disasters appears to be increasing around the world, said Dr. Mark Keim, an emergency-medicine physician and the founder of DisasterDoc LLC. These include, for example, not only weather- and water-related disasters, but also geological disasters, such as earthquakes, and biological disasters, such as pandemics.

Data from the past 50 years show that 41 percent of all global disasters are related to extreme weather or water events, Keim said here on Thursday (Feb. 16), at the Climate & Health Meeting, a gathering of experts from public health organizations, universities and advocacy groups that focused on the health impacts of climate change. [5 Ways Climate Change Will Affect Your Health]

Experts in climate change predict that extreme weather events will increase in either frequency or severity, and these events are a very serious public health burden, Keim told Live Science.

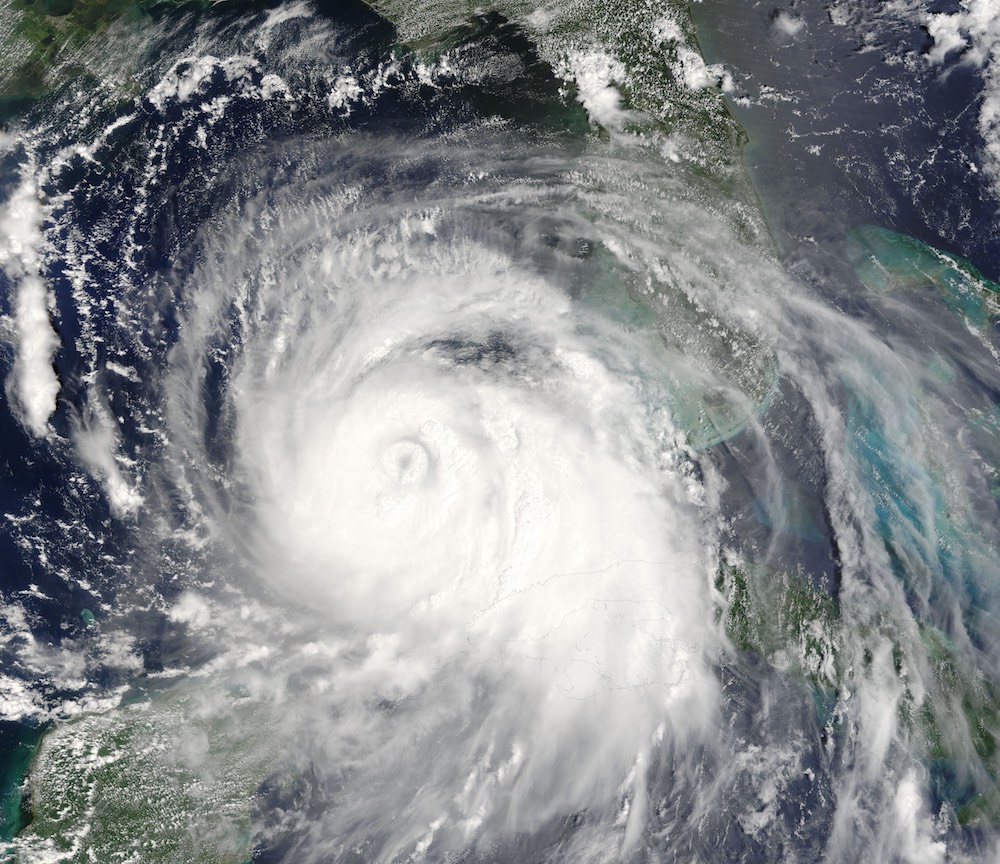

Extreme-weather events fall into three categories: high-precipitation disasters (such as hurricanes and tornadoes), low-precipitation disasters (heat, droughts and wildfires) and sea-level rise disasters, Keim said. High-precipitation and low-precipitation disasters are currently affecting the United States, he added.

High precipitation disasters

High-precipitation disasters, which include storms, floods and landslides, can kill people in a variety of ways, Keim said. People can die from falls, electrocutions (from downed power lines), drowning (for example, during a hurricane) or asphyxiation (in a landslide), Keim said. In the United States, more deaths occur during the clean-up phase of hurricanes than during the actual storms, he added.

Data show that among people with any type of severe injuries, 50 percent die immediately, and another 30 percent of severely injured people die within the first hour, Keim said. (These data apply to any type of severe injury, from car accidents to hurricanes, he said.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That means that 80 percent of all deaths from severe injuries occur within 1 hour of the event, which is deemed "the golden hour," he said.

But during a disaster, with winds blowing or the earth shaking, it's nearly impossible to reach victims within that golden hour, Keim said. So if doctors and experts want to reduce the number of deaths, they need to take a different approach: prevention, Keim said.

Deaths from tornadoes, for example, have decreased tenfold over the past 30 years, thanks to improved communication about storms and education, he said. Improved forecasting and early warnings allow people to get out of the area, he added.

Low-precipitation disasters

Low-precipitation disasters also threaten health, Keim said. These include heat waves, droughts and wildfires.

Kim Knowlton, an assistant clinical professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York City, who also spoke at the meeting, elaborated on the health risks posed by heat.

"There is a clear warming trend and that threatens health," Knowlton said. "Heat waves, which are extreme heat events that last several days, are the No. 1 cause of U.S. weather fatalities, on average, over the last 30 years," she said.

Extreme heat poses a problem because it disrupts the body's natural ability to regulate its temperature, Knowlton said. [Roasting? 7 Scientific Ways to Beat the Heat]

Normally, the body regulates its internal temperature via the heart and lungs, Knowlton said. When its hot out, the heart beats faster, we breathe faster and we sweat to cool off, she said. But in extreme heat, these functions can't rid the body of enough heat, and our internal temperature rises, she said.

This can lead to a range of heat-related illnesses, from mild ones, such as heat cramps and fatigue, to more serious ones, such as fainting and heat exhaustion, to severe ones, such as heat stroke, which is fatal in more than half of all cases, Knowlton said.

But extreme heat doesn't only kill people directly through heat-related illnesses. It can also increase the risk of death from heart disease, respiratory diseases, kidney diseases and other illnesses, because of its wider effects on the body, Knowlton said.

Many people are vulnerable to heat-related illnesses, Knowlton said. These include infants, children, the elderly, outdoor workers, athletes, people with medical conditions, pregnant women, the poor, the homeless and people who live in cities, she said.

In addition, certain drugs, such as blood pressure medications, antidepressants and allergy medications, make people more susceptible to heat, Knowlton said.

This means that people who are "already struggling to stay healthy will be more challenged as climate change and heat continues," she said.

Originally published on Live Science.