Tiny, Underwater Robots Offer Unprecedented View of World's Oceans

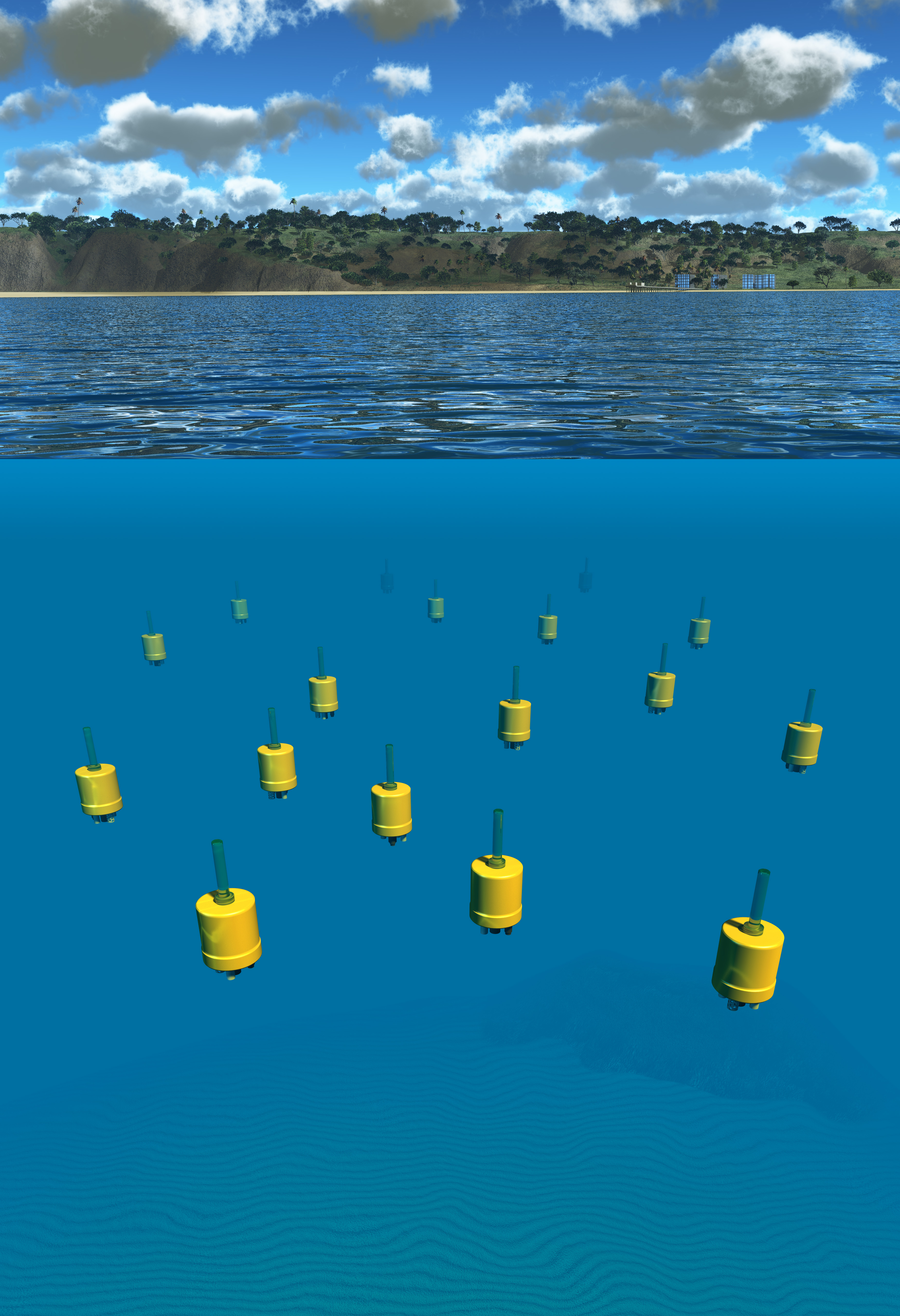

Robots the size of grapefruits are set to change the way scientists study the Earth's oceans, according to a new study.

Though space is often known as the "final frontier," the oceans of our home planet remain much of a mystery. Satellites have played a big role in that divide, as they explore the universe and send data back to scientists on Earth. But now, researchers have developed a kind of satellite for the oceans — autonomous miniature robots that can work as a swarm to explore oceans in a new way.

For their initial deployments, the Mini-Autonomous Underwater Explorers (M-AUEs) were able to record the 3D movements of the ocean's internal waves — a feat that traditional instruments cannot achieve. Study lead author Jules Jaffe, a research oceanographer at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said current ocean measurements are akin to sticking a finger in a specific region of the water. [In Photos: The Wonders of the Deep Sea]

"We can move the finger around, but we're never in two places at the same time; so we basically have no sort of three-dimensional understanding of the ocean," Jaffe told Live Science. "By building this swarm of robots, we were in 16 places at the same time."

Each underwater robot is about the size and weight of a large grapefruit, Jaffe said. The bots are cylindrical and have an antenna on one end and measurement instrumentation on the other.

The swarm's first mission was to investigate how the ocean's internal waves moved. One of Jaffe's colleagues theorized that aspects of plankton's ecology is due to ocean currents pushing plankton together and pulling it back apart. However, scientists did not have the three-dimensional instrumentation capabilities to be able to verify those theories. Over the course of a few afternoons, Jaffe and his team deployed the M-AUEs in hopes of proving (or disproving) the theory.

"We could see this swarm of robots be pushed by currents, getting pushed together and then get pushed apart," Jaffe said. "It's almost like a breathing motion, but it occurred over several hours."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The theory was based on ocean physics, water density and internal wave dynamics, but the scientists had never seen the real-time movement of ocean water in 3D, Jaffe said.

And although their initial deployments were focused on the 3D mapping of internal wave dynamics, Jaffe said there are many other applications for the robot swarms.

For instance, with slightly different instrumentation, the robots could be deployed in an oil spill to help track the harmful toxins released. With underwater microphones, the swarm could also act as a giant ear, listening to whales and dolphins.

"We're not yet churning them out like a manufacturing facility, but we think we can answer a lot of questions about global ocean dynamics with what we have," Jaffe said of the couple of dozen robots the scientists have now. "And we are planning on a next generation, which hopefully would have more functionality and would maybe be even less expensive."

Details of the robot swarm were published online today (Jan. 24) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus