Captain Cook's Notes Describe Now-Vanishing Arctic Ice Wall

The meticulous records of Capt. James Cook, the intrepid British explorer famous for exploring Australia and the Hawaiian islands, have found a new and modern-day value: Helping climate change scientists understand the extent of sea ice loss in the icy Canadian Arctic, according to a new study.

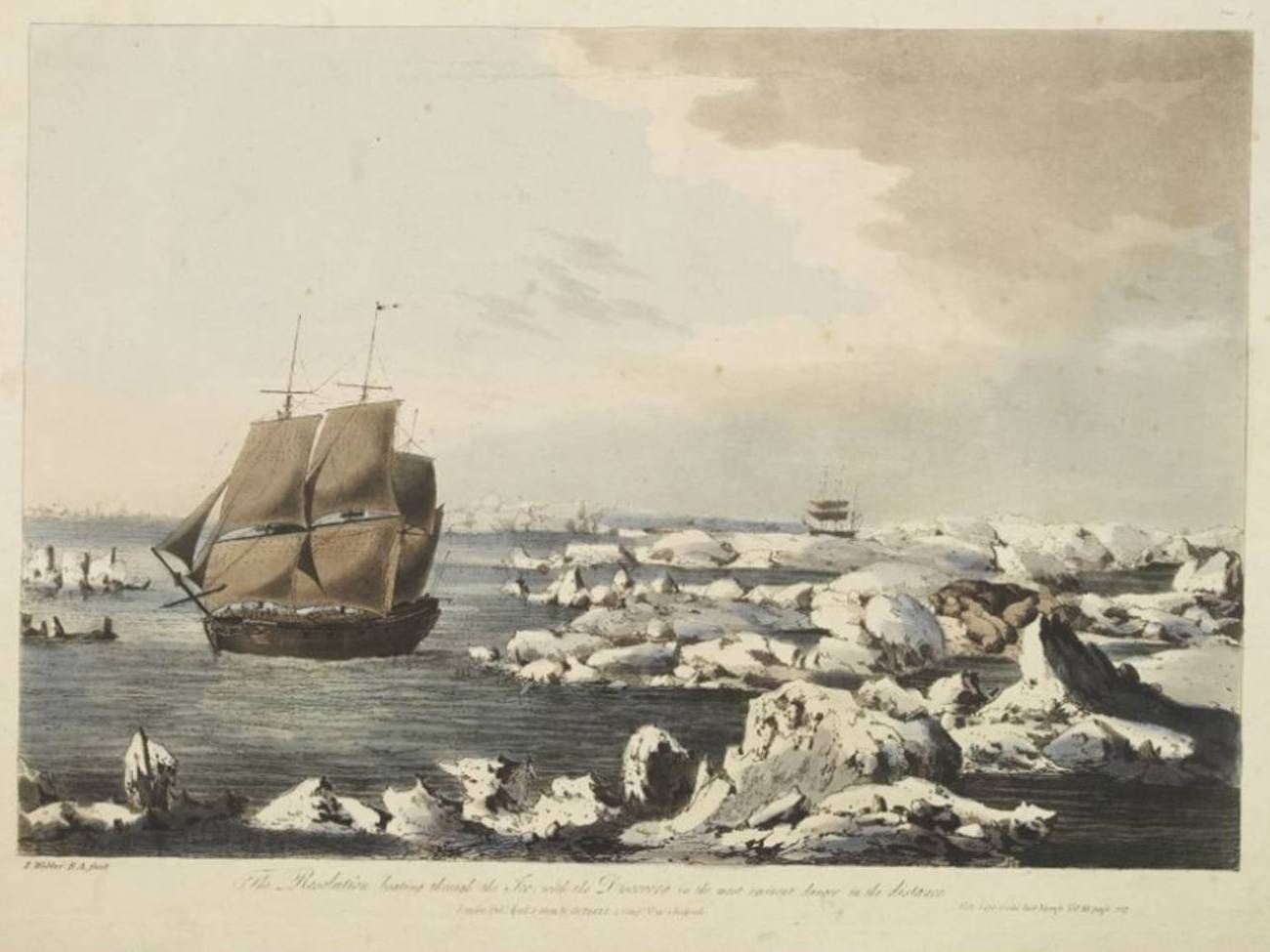

Notes, charts and maps created by Cook and his crew during an Arctic expedition in August 1778 carefully documented the position and thickness of the ice barring the explorers' way. They were searching for a corridor that they thought would link the Pacific and northern Atlantic oceans and offer a new maritime trade route between Great Britain and the Far East.

Cook never found that route, known today as the Northwest Passage. But his observations and those of his crew provide the earliest recorded evidence of then-extensive summer ice cover in the Chukchi Sea. That part of the Arctic Ocean lies between Alaska and Russia. These records, when compared to modern observations of sea ice, indicate how dramatically Arctic ice cover has changed — particularly in recent years, according to study author Harry Stern, a researcher with the Polar Science Center at the University of Washington. [On Ice: Stunning Images of Canadian Arctic]

While Cook wasn't the first explorer to search for the Northwest Passage — nor was he the last — he was the first to chart the ice border that bisected the ocean north of the Bering Strait, Stern said in the study. Cook was also the first to attempt the approach from the Pacific side by traveling up the North American coast, Stern said.

At the time, finding this route — which would have expedited and strengthened trade with the Orient — was an especially urgent goal for Great Britain. In fact, the House of Parliament issued an act in 1745 offering a reward of up to 20,000 pounds (about $24,978 U.S.) for finding and mapping the passage, according to archives of the Royal Greenwich Observatory maintained by the University of Cambridge Digital Library.

Stern, who studies climate and Arctic sea ice, researched Cook's journey for an essay the climate scientist contributed to the book "Arctic Ambitions: Captain Cook and the Northwest Passage" (University of Washington Press, January 2015). As Stern studied the archival documents from the 1778 voyage, he realized he was looking at the very first detailed maps of the ice edge in the Chukchi Sea, he said.

"Ten or twelve feet high"

Prior to Cook's expedition, maps of the area offered little detail or were spectacularly inaccurate; one Russian map that Cook used for reference indicated that Alaska was an island, Stern wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cook sailed through the Bering Strait on Aug. 11, 1778, but his progress was abruptly halted near Alaska on Aug. 18 by ice that was "as compact as a Wall and seemed to be ten or twelve feet high at least," he wrote in his journal.

In a journal entry the next day, Cook described tracking the edge of sea ice hidden in the fog by listening for the sounds of bellowing walruses, which he called "sea horses." Stern pointed out that this may be the first recorded use of remote sensing — obtaining information about a distant object by calculating energy it emits — to locate the position of sea ice.

An impenetrable wall

Cook scoured the edge of the ice wall for 11 days, but though he traveled as far west as the coast of Siberia, he couldn't find an opening. Forced to retreat south, Cook vowed to resume the search the following summer, but he never returned to the region, and died in Hawaii six months later.

Still, Cook's thwarted efforts collected important data about Arctic ice, the researchers said. His records of the impenetrable ice wall's location and scope were so accurate that the notes could be used in alignment with later maps. This helped scientists to clarify historical sizes and positions of the ice edge, and to determine how it varied over time, Stern said.

And over hundreds of years, the size of the icy wall Cook originally documented fluctuated somewhat from year to year but didn't shift dramatically — until the 1990s, Stern told UW Today. Since then, changes have been significant, he said.

"The summer ice edge in the Chukchi Sea is now hundreds of miles farther north than it used to be," Stern said.

It wasn't until the beginning of the 20th century that the Northwest Passage was navigated in its entirety — albeit in a relatively small ship — in an expedition led by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen between 1903 and 1906. And in 2007, with Arctic sea ice at its lowest levels in 30 years, the passage opened enough to accommodate large cargo ships and research vessels.

Might Cook have found that elusive passageway in 1778, if sea ice cover were more like it is today? Probably, Stern told UW Today — but that doesn't mean it would have been easy.

"One thing hasn't changed: It's still dangerous to navigate through ice-covered waters," Stern said.

The findings were published online Nov. 3 in the journal Polar Geography.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus