295-Million-Year-Old Frog Relative Immaculately Preserved in Fossil

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

SALT LAKE CITY — Long before dinosaurs walked the Earth, a teeny-tiny amphibian swam around a lake surrounded by large mountain ranges, using its minuscule jaws to nab insects and other small prey, a new study finds.

The amphibian was still in its larval stage when it died (in frogs, this creature's distant relatives, the larval phase is known as the tadpole stage), and it expired on its back, belly-up, said study lead researcher Johan Gren, a doctoral student of geology at Lund University in Sweden.

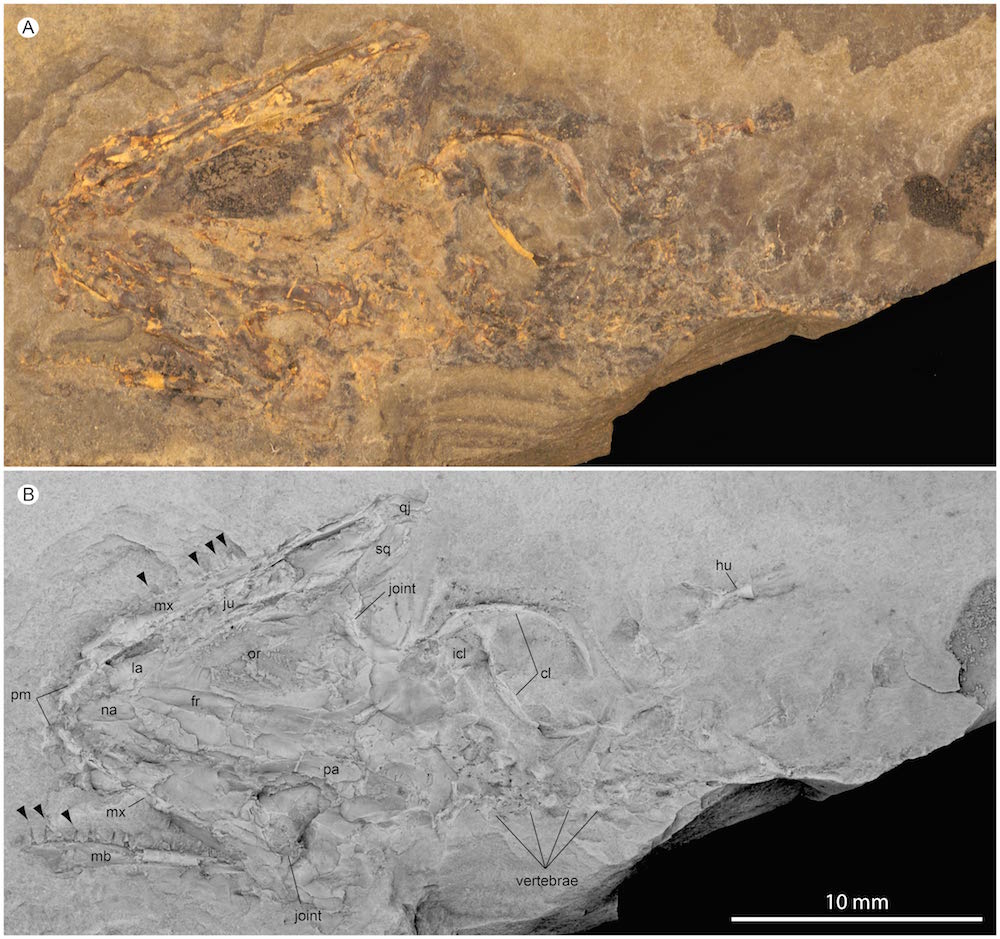

The upper half of the body of this 295-million-year-old amphibian was exceptionally well preserved, the researchers found. For instance, most of the skull and braincase are present, as are several vertebrae, one of its front limbs, part of its lower jaw and some of its soft tissues, including a blackish film within its left eye socket, Gren said. [In Photos: Giant Amphibian Ruled Ancient Rivers]

Article continues belowThe teeny creature, just 1.5 inches (4 centimeters) long, is a temnospondyl, a group of early four-legged amphibians that are now extinct, and ranged in size from tiny to giant, Gren said. Had it lived to adulthood, the newly identified temnospondyl "could have grown to tens of centimeters," or maybe 8 to 12 inches, he noted.

Researchers discovered the fossil about 15 years ago in the Saar-Nahe Basin, located in southwestern Germany. The region is known for its many fossils; scientists also have found invertebrates, cartilaginous and bony fishes, and other amphibians in the area, which was once filled with numerous lakes that rippled between two mountain chains, Gren said.

Though tiny, the temnospondyl got star treatment: High-powered microscopes revealed a preserved layer of soft tissues outlining the amphibian's body, and computed tomography (CT) provided the scientists with a 3D image of the fossil, Gren said.

Gren and his adviser, Johan Lindgren, a senior lecturer of lithosphere and biosphere science at Lund University, plan to continue to study the "early frog relative," Gren said. He presented the unpublished findings Wednesday (Oct. 26) here at the 2016 meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus