'Frog-amander' Fossil Fills Evolutionary Gap

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

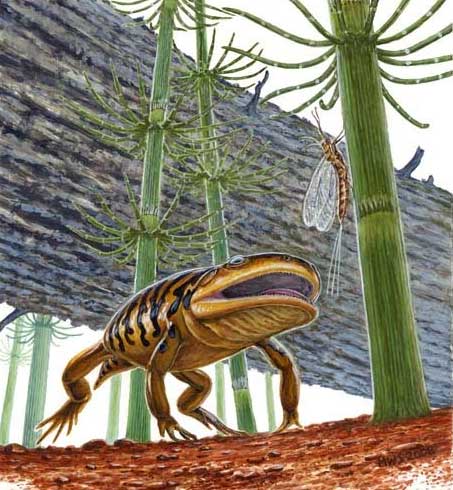

A frog-like creature with a stubby tail once paddled through a quiet pond in what is now Texas, snapping up mayflies while keeping an ear out for bellowing mates, new fossil evidence suggests.

That was about 290 million years ago.

In 1995, the amphibian specimen was discovered in fish quarry sediments in Baylor County, Texas, though it wasn't until recently that paleontologists inspected and described the new species. Called Gerobatrachus hottoni after its discoverer Nicholas Hotton, a paleontologist at the Smithsonian Institution, the creature represents a transitional amphibian, sporting features of both frogs and salamanders.

"This amphibian is from near to the point where frogs and salamanders first split," said lead researcher Jason Anderson, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Calgary in Canada. "This is kind of an early frog-amander."

The finding, detailed in this week's issue of the journal Nature, supports the idea that frogs and salamanders evolved from one ancient amphibian group called temnospondyls.

Like modern salamanders, the fossil of Gerobatrachus has two fused bones in its ankle. And like modern frogs, the frog-amander sports a large ear drum, or tympanic ear, which Anderson said the ancient amphibian likely used for hearing calls from mates.

"I suspect that many of the temnospondyls have a similar sort of [tympanic ear] system," Anderson told LiveScience. "But of course unless we were able to build a time machine and go back and listen to these guys call, we won't know for sure."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rather than hopping, this amphibian likely walked on land and swam in water, with the ability to lunge after prey, Anderson said. In fact, along the evolutionary history of amphibians, frogs didn't begin hopping until the Jurassic or Triassic period. (The most definitive hopping frog fossil is dated to the Triassic, which spans from 248 million to 206 million years ago.)

"It was found in sediments from a quiet pond with a lot of fish fossils, but I suspect it was equally comfortable on land or in water," Anderson said.

The fossil also showed several tiny teeth that had a specialized trapping feature seen in all modern amphibians at some point in development. The teeth are able to hinge inward when catching prey. "It allows food to go in, but it can't get back out," Anderson said.

The new species, spanning less than 5 inches (12 cm) from nose to tip of tail, provides a marker of when frogs and salamanders went their separate ways along the evolutionary path toward modern forms.

"With this new data, our best estimate indicates that frogs and salamanders separated from each other sometime between 240 [million] and 275 million years ago, much more recently than previous molecular data had suggested," said study team member Robert Reisz of the University of Toronto Mississauga.

The research was supported by the Museum of Natural History (le Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle) in Paris and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Earlier this week, a separate team announced finding a yellow tree frog in Panama that also had transitional features.

- Video: How Salamanders Walk and Swim

- Top 10 Useless Limbs (and Other Vestigial Organs)

- Images: New Amphibian Tree of Life

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus