Experimental Drug Mixture Protects Monkeys from Ebola Virus

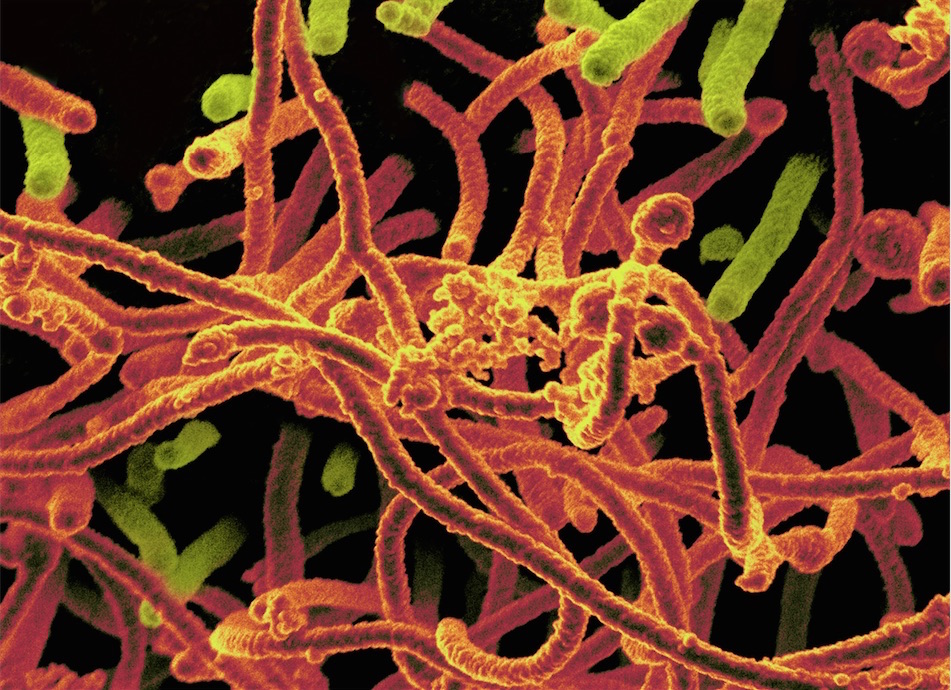

An experimental drug mixture can successfully fight the Ebola virus in monkeys, fully protecting them from lethal infections, according to a new study.

The finding may pave the way for a therapy that is broadly protective against Ebola viruses in Africa, researchers say. Unlike a vaccine, the new drug mixture is intended to treat Ebola after a person has been infected with the virus.

The Ebola outbreak that began in 2014 in West Africa was the largest known outbreak of the virus in history, causing more than 28,000 cases of Ebola virus disease and 11,000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Symptoms of Ebola virus disease include fever, muscle pain, severe headache, diarrhea, vomiting, and sometimes bleeding from the nose, eyes, mouth, ears and elsewhere. Although West Africa was declared Ebola-free in mid-January of this year, a few cases have since occurred in Sierra Leone, and the region remains at risk for more cases of Ebola virus disease.

The outbreak spurred research into drugs and vaccines to combat the deadly virus. In 2014, researchers developed an experimental drug called ZMapp, which was given to a handful of Ebola patients. This new therapy consisted of three different antibodies, which are molecules that can bind to foreign proteins.

In early studies of ZMapp, the drug successfully treated 18 monkeys infected with the Kikwit strain of Ebola that struck Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1995. This previous research found that all of the monkeys recovered from the infection without showing any lingering effects.

Now, researchers have developed an anti-Ebola drug mixture, or "cocktail," made from only two antibodies and seems at least as effective as ZMapp, the study's authors said. This simpler formulation may simplify production, reduce costs, accelerate regulatory approval of the drug and improve safety by reducing potential complications, the researchers said. [5 Viruses That Are Scarier Than Ebola]

"Bringing the cocktail down to two antibodies is very good news," said study co-author Gary Kobinger, an immunologist, virologist and director of the Infectious Disease Research Center at Laval University in Quebec City. "It'll be easier to produce and save a lot on the costs."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new cocktail, called MIL77E, uses two of the three antibodies in ZMapp. Prior research found that two of the three antibodies in ZMapp were very similar in the way they target the Ebola virus, suggesting that they were redundant — so MIL77E uses just one of those two antibodies.

Whereas ZMapp was generated in a close relative of the tobacco plant, the new cocktail was generated using modified Chinese hamster ovary cells. The idea was that the use of mammalian cells would produce a drug more useful in the human body than a drug manufactured in plant cells. The researchers also tweaked certain parts of each antibody to better resemble human antibodies.

Three days after three monkeys were infected with the Makona strain of the Ebola virus (the one responsible for the current outbreak), all three monkeys that were given the two-antibody cocktail survived. In contrast, only two of the three monkeys given a similar formulation of ZMapp survived.

An infection that has also caused Ebola outbreaks in Africa is Sudan ebolavirus, which is related to but distinct from the Zaire ebolavirus that recently struck West Africa.

Kobinger noted that adding an antibody against Sudan ebolavirus to MIL77E could lead to a three-antibody cocktail that could combat most Ebola cases in Africa.

"This work really opens the door to cocktails that will have broader potency, that will be potent against more than one species of Ebola," Kobinger told Live Science. "This could cut down the risk of having resistant mutant viruses escaping."

The scientists detailed their findings online March 9 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @livescience, Facebook &Google+. Original article on Live Science.